By Glenn Dunks

A movie like Emily Cohen Ibañez’s Fruits of Labor doesn’t need to explicitly say the quiet part out loud. But it does anyway. In its early moments, sitting side-by-side are a scene of a second-generation teenage child of immigrants working to help feed her family by picking strawberries in the Californian morning sun followed by a scene of that same child, a high school senior, in class listening to her teaching discuss ‘working the fields’ and the class/social inequalities that come from this poorly-paid, but essential work.

A movie like Emily Cohen Ibañez’s Fruits of Labor doesn’t need to explicitly say the quiet part out loud. But it does anyway. In its early moments, sitting side-by-side are a scene of a second-generation teenage child of immigrants working to help feed her family by picking strawberries in the Californian morning sun followed by a scene of that same child, a high school senior, in class listening to her teaching discuss ‘working the fields’ and the class/social inequalities that come from this poorly-paid, but essential work.

Furthermore, one doesn’t need to extrapolate very much to see the unavoidable illusions to modern day slavery as Ashley Solis lives in a house where up to 12 families share living spaces and one single bathroom.

It’s not surprising that Oakland-born director Ibañez of Colombian heritage has a history in anthropology. She shows an obvious flare in observing the Solis family, sometimes in uncomfortable close-up. It’s also not surprising that this is only her second feature, following on from her 2015 documentary Bodies at War.

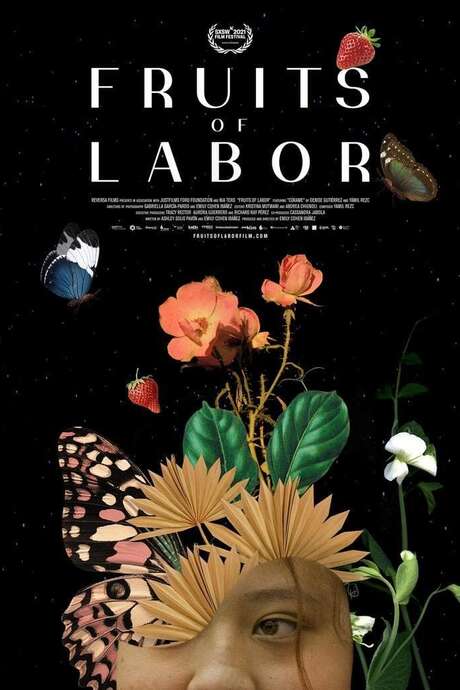

I have not seen that title, but this follow-up does suffer occasionally from the lack of a strong spine with perhaps too much glossed over and left to the viewers imagination. At only 78 minutes long, Ibañez—clearly talented, if green—could have spent a bit less time on rather rudimentary visual metaphors about butterflies and blooming flowers that could have instead been better spent further coloring in the lines of this family’s very real, lived experiences. For example, we are shown that Ashley is struggling in school and worries she won’t be able to graduate, but rather abruptly is shown to be a model student. Likewise, much of the film’s narrative is built around Ashley’s desire to go to prom including finding the perfect dress and nails, but we only catch a brief glimpse of the event.

But where Fruits of Labor really shines is in how it so compassionately tells the story of this one family. The broader concern of rights for immigrants and their children is obviously the core idea here as the Solis family fights to survive and somehow eke out a better life despite all of the obstacles in their way. Filmed in 2018, Trump lingers in the background, but is thankfully left mostly to television screens even as the reality of potential ICE raids hovers. In one sequence, for example, Ashley seeks legal standing should something happen to her mother (a housecleaner in Monterey).

This isn’t a documentary with any interest in showing the anti-migrant hostility like protests and television talk-show hosts. I presume that’s because Ibañez is smart enough to know we are already very well aware of it. The Solis family clearly have it tough enough as it is, they don’t need a movie to magnify the racism they surely live with every single day of their lives Although that doesn’t stop the film from hinting at the obvious that most “immigrants are stealing our jobs” bigots wouldn’t last a week in this line of work. For that, its to be commended, finding moments of grace in Ashley’s world within the hardships.

Release: Screens on PBS' POV this coming October 5th.

Award chances: POV factors into a lot of award shows as an ongoing series—particularly the News and Documentary Emmys and the International Documentary Association—which then spotlight individual titles. They always have strong titles and Fruits of Labor is probably just not big enough to feature as one above the rest.