While we're at the dawn of a new year, the 2021 awards season is far from over. Academy Award nominations are still a month away, so there's plenty of time to champion one's cinematic favorites before hope withers away on Oscar morning. To start 2022 off on the right foot, let's investigate our predilect craft category – Best Costume Design. There are plenty of glamorous contenders, but the one I'm most rooting to see nominated chooses a more understated path to greatness. Costume designer Malgosia Turzanska outfitted David Lowery's adaptation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight in simple designs rich in visceral textures, colors shining through the shadowy cinematography, ancient symbolism, and more…

Turzanska's approach to the material is evident from the very first shot of Dev Patel's Gawain in a costume that owes little to history. The poem isn't historical in nature, so why should the film? How do you costume a historically accurate version of a 14th-century text about a 6th-century world of legend that might never have existed, even beyond the obvious fantasy? While there was evident period research, there's also a taste for stylization in the images Lowery and company conjure. What grounds The Green Knight isn't a similarity to Medieval times but a bond with the world that surrounds its people, the crumbling reality of bodies in pain, the ardor of lust.

That's even more important when one moves into the realm of the unconscious. We first see Sir Gawain in a dream, perchance a premonition. He sits on a throne, covered in yellow velvet, his crowned head aflame. That hollow crown is the most potent piece of iconography in the entire flick, a masterpiece of Byzantine sainthood synthesized in two cold circles - one encircling the skull with crosses and metal plates, the other a halo. The vertical holiness of the design was challenging to figure out, but thankfully, Turzanska had the help of David Samuel Houghton. He built prototypes and mockups of cardboard and paper to perfect the shape.

It resulted in an image of ominous religiosity. Like the entire wardrobe, it harkens back to history and a sense of ancient age while being willfully modern in its invention.

Beyond dreams, the Camelot of The Green Knight is no land of pride and joy. What glory there is has grown tired, ripened to the point of rot. The poor people look like extensions of the stones that form the place of Arthurian legend. It's a quiet storm of rock shades and muddy browns, a world in the winter of its existence. Some figures do have vitality, but they aren't tied to the laws of Men. Gawain's mother is Morgan Le Fey, the king's cousin whose coven of witches all dress in ochers and greens, the forest in human form. They're full of nature, full of life, a stark contrast to the peasants and the court, a whisper of dusty greys and Marian blues.

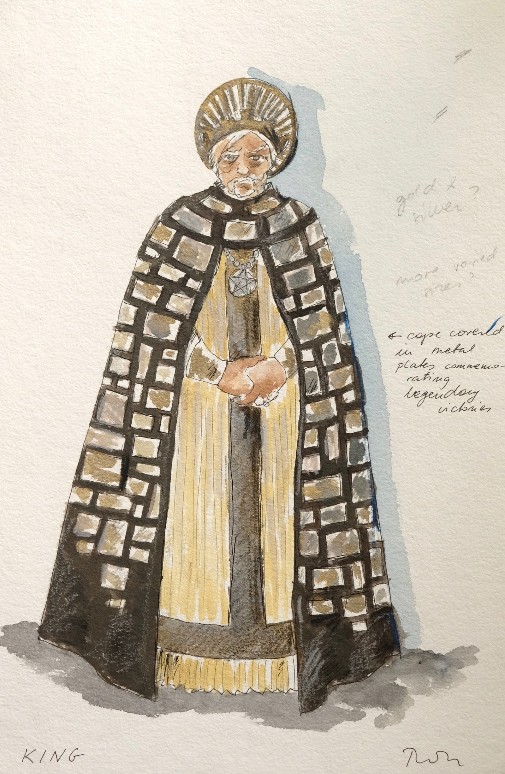

It's the difference between a living body and a corpse, an embrace of the natural world and a rejection of it, primitive customs and civilization, the pagan and the Christian, the woods and the cathedral. So it'd be only logical that those who wear the crown epitomize this Camelot. Arthur and Guinevere thus represent two forces of Medieval rule – war and church. He's ornamented with painted tin panels depicting histories of the battlefield. Her dress is similarly decorated, only, instead of bellicose victories, she's got votive offerings. These Milagros are of Iberian and Latin American origin, the sort of glittering badge you might pick up as you partake on a holy pilgrimage.

The costume designer described these two figures as burdened by gratitude, covered in tokens of thankfulness from the people they rule and saved. Yet, under all that goodwill, they can barely move. This physical cumbersomeness gets at the sartorial paradox within The Green Knight's idea of royalty. Pageantry defines them as God-chosen rulers, but there's human decay beneath the gold. One must remember that this is an old Camelot with an old king on the throne. Still, their crowns shine like dim suns. Apart from the monarch's golden headpieces, everything else is silver and steel. You can feel the coldness of metal emanate from the screen as the camera gazes upon a mirthless Christmas feast.

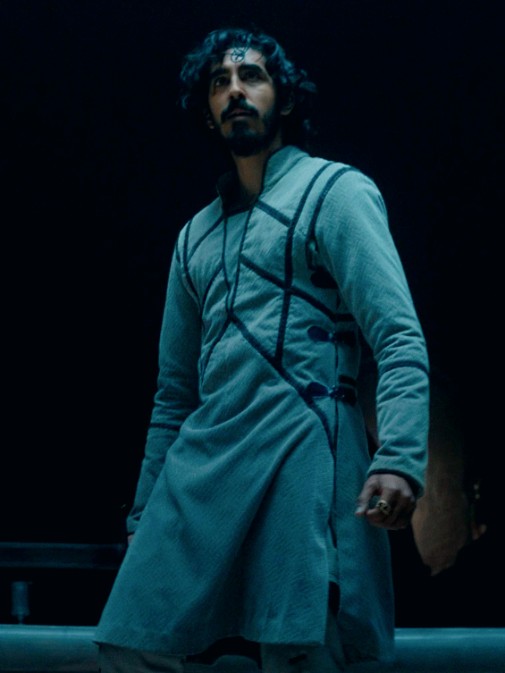

Despite his parentage, Gawain is a product of this early Medieval rot, indolent and aimless, soft to a fault, cruel. So it's only proper that his costume reveals the corruption that separates the man from his maternal origins. At the feast, he's not dressed for a party. Wearing a gambeson – the cloth undergarments of armor, what one might have beneath a shirt of chain – he looks ready for battle even during a holiday celebration. It helps underline the idea of a tired world, massacred by violence that has polluted its very essence. It's marrow-deep by this point, in-dissociable from quotidian life.

No wonder his mother will do anything to make her son prove his worth. That's where the Green Knight comes in, holding his mighty ax and proposing a deadly game to those sited at the Round Table. If possible, the knight that interrupts Christmas looks even older than the decrepit monarchs, their kingdom. Invoked by Morgan and her coven, the monster's armor bears the same Sabaic words and runes the witches carve during the invocation ritual. The plates of his armaments are corroded, and, at points, it's difficult to distinguish costume from makeup, barkcloth cape from magical flesh. He comes from a reality that existed far longer than anything else on-screen, a world destroyed by this new one.

To honor that wizened quality, that connection to Nature, as well as her director's veganism, the costume designer found unexpected materials to bring her ideas to life. First and foremost, Turzanska looked for replacements for fur and leather. However, a repudiation of animal products didn't mean a fall into the unsustainable world of polyester and plastic. Instead, the costume designer found materials with natural origins, sourcing leathers made from pineapple, mushroom, coconut, and tree bark. This is most apparent in the Green Knight's costume, but it applies to all the clothes. Notice, for example, the courtiers with hands encased in sculpted prayer, their cloth robes painted with clay, dried until it cracked like elephant skin.

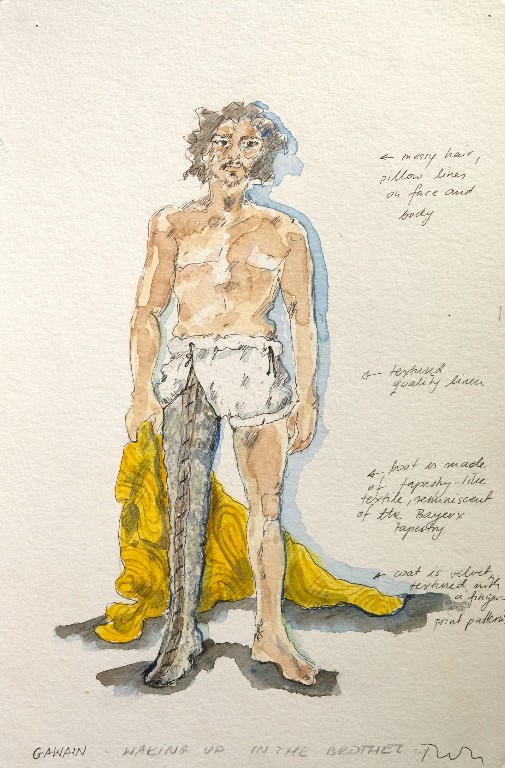

As we leave behind the Christmas feast, a quick year passes, and Gawain is set upon a long journey searching for the Green Knight.

This turn of events brings us to the film's best costume, a chromatic shock of utter genius. Looking at the bright jaundiced hue of Gawain's cloak, I was reminded of mustard and saffron. However, in interviews, the costume designer has provided another natural connection, one more specific to the Irish landscapes where the film was shot. The yellow velvet shines with the tonality of gorse, an invasive Irish plant that dots the ground and once became an emblem of Brittany and Cornwall, Scottish clans, and Galician kingdoms. In parts of Britain, it's still a traditional May Day gift, a flower for young lovers.

The cloak is quilted and padded, traditional ways to protect the body from frost and harm, long before plate armor became the norm amid noble warriors. Nevertheless, the stitching follows no Medieval patterns or rules. Instead, Turzanska came up with the shape of a magnified fingerprint. The detail highlights how much Gawain's odyssey is about identity, selfhood, and choice, rather than a mere magical misadventure. The key to this mission is the belt Morgan gifted him, a girdle that will protect him from all injury. As with all designs in The Green Knight, the girdle is relatively simple. It looks like moss turned to fabric, green nervures with hints of gold thread. The magic is enclosed within the folds, pulsing with life, like entrails fashioned into a sash.

If the umbilical cord of the girdle connects him to paganism, so does the shield remind us of Gawain's desire to be part of a Christian kingdom. On its inside, a Holy Virgin appears clothed in blessed azure, the color of Arthur's court and his knights. Maybe because of that, it doesn't last long against the dangers outside Camelot. A thief appears in the middle of a field where a battle was fought. Stealing from the corpses, he wears his loot, a necklace of armor parts, and a collar of purloined chainmail. Upon the robbery, he cracks Gawain's shield and takes the ax. Only a mystical encounter with a headless saint in a spectral chemise manages to return the weapon to Morgan's son. However, there's no thief nor ghost as dangerous as selfish desire.

Near the end of his travels, Gawain meets a lord and lady. Like beacons of temptation, they live within an anachronistic world of Gothic Revivalism. Their costumes befit their abode.

To distinguish Alicia Vikander's Lady from Gawain's lover, Essel, Turkanska chose an antagonistic design philosophy drawn from each character's distinct environments. The sex worker from Camelot wears simple cloth cut in rectangles sewn together, bells adorning her costume as it was custom for prostitutes. Their presupposed uncleanliness made them pariahs whose presence should be signaled by a twinkling alert. The noblewoman, instead, is bedecked in tailored garments, intricate seams emulating the architectural lines of her palace.

Another face of this lady is her lord. Temptation is cobalt and fur, which they both wear. Notice how the lord and lady look chromatically interchangeable. This is because they are two faces of the same coin. The luxuriant luxury of these sensual nobles extends to Gawain, too. Dressed in their generosity, he trades his battered costume for a tunic of pleated dupioni silk, glittering silver against Patel's coppery skin. Gawain might leave behind the new outfit and continue his journey in the yellow shroud, but the sticky temptation follows him, invisible. When it comes time to confront the Green Knight, a dream of cowardice reveals what might await the knight if he chooses wrong.

He sees himself trade in the mud-covered velvet for new attires back home in Camelot, never taking off the girdle of indestructibility. Eventually, he becomes king and dons the Marian blue of a Christian ruler, further turning his back away from the paganism of the Knight, the witches, the mother. He gives in to the temptation in blue, a new bride by his side. She, too, wears the color doted across her face, the middle point between a tribal design and Christian iconography. In nuptial pleats, she arrives with cerulean courtiers leaving the coven and a bastard son as the only remnants of the Gawain that could have been. His doomed child by Essel appears only briefly, but he dons green silk, a reminder of what his father evaded, the fate he dishonorably ran from.

The vision ends with death. At the end of a lifeless life, the king eviscerates himself by ripping out the magical sash. At last, a choice must be made, and the clothing gives you all the clues to know what the right one will be. It's visual storytelling at its best, costume as poetry. In short, give the Oscar to Malgosia Turzanska.