Before he became a film director, Alejandro Loayza Grisi was a still photographer. Looking at his debut feature, Utama, it's easy to see the remnants of a photographer's sensibility, now transmuted into cinematic storytelling. Along with DP Barbara Alvarez, Grisi has framed the Bolivian highlands as a presence more important than any human. The cliché of the landscape being a character is not only present but transcended, to the point that the natural vistas become something of a cosmic deity. They're titan-like, cracked earth making up a wrinkled visage. The river is its mouth, once a gaping maw spewing life. Nowadays, it's just the sliver of a grimace, growing thinner, drying into oblivion.

This land is dying, and so are its people…

Virginio (José Calcina) and Sisa (Luisa Quispe) are stubborn people. Most of their neighbors migrated to the city, leaving behind a countryside quickly becoming a wasteland. As temperatures rise and rain refuses to fall, life becomes unsustainable. And yet, the couple of Quechua elders persists, against all hope and reason. Indeed, their entire life is ruled by cycles of desperation, pilgrimages to the drying river that mark the passing time like a metronome of thirst. Every day, the shepherd travels great distances searching for water so his herd of llamas can drink and survive another scorching afternoon.

These noble creatures, crowned with colorful ribbons, are a vision of withering vitality, a parade of bumbling animals at the mercy of their human masters. Still, No matter how fragile the llamas might look, every one of them is in better condition than Virgilio. We meet him as he walks into the sunset, a man reaching the twilight of a long life. Indeed, his body is giving up on him, starting with lungs that can't hold air, wheezing away in sleepless nights. The situation isn't any better during daylight. Though he tries to hide the sickness from Sisa, the man knows his time is coming to an end.

Because of such fate, his decision not to leave his people's ancestral home becomes solidified in spiritual resolution. The land itself seems to speak to him, sending omens as winged messengers. The condor of Andean legend flies above him in the sky, and, just like the bird, Virginio would rather die on his own terms. He'll sooner crash-dive into a rocky grave than waste away on a hospital bed. But, of course, not everyone thinks like the dying man, including Clever (Santos Choque), their grandson who appears one day. He's come to visit the couple, somewhat against the will of a father who's cut ties with his immovable parents.

The intrusion of an outsider's eye serves as a catalyst, igniting Virginio's combative nature, his open defiance in the face of a changing world. Though bound by blood, the older man's eyes almost see the youth as an enemy, an embodiment of rejection. He doesn't even speak his grandparent's chosen idiom, barely communicating in broken Quechua. Instead, Spanish taints his tongue, a language brought across the Atlantic by the colonizers who decimated Bolivia's indigenous people, the true children of this land. He's a rejection of the old ways and what they meant, still mean. He's a future that spits on the past's face, eroding tradition through good intentions.

And so starts a war of wills, intergenerational warfare that never works itself above a gentle whisper. One feels the familial love coursing through each figure, but neither man is willing to bend, least of all Virginio. Sisa stands in the middle, a primordial mother who nourishes and begs for understanding, who begs for life in a story defined by death. Though the human drama is simple, minuscule to the point of minimalism, one soon realizes that there's much more going on than just the quarrel of Clever and Virginio.

Utama's English title is Our Home, pointing us towards the very definition of home as a crucial point in the film's thesis.

Clever's conception is modern, pragmatic, with a shadow of sentimental sincerity. To him, home is where the heart is and where he and his people can thrive. For Virginio, home is the land that birthed his ancestors, the earth from which their way of life once blossomed into existence. To leave would be to abandon all that he believes, all that he is, to capitulate to the modernity that's killed everything in its sight. Cultural genocide and history crash into the tragedy of climate change, another evil that the modern folk quickened, fortified, allowed to dry up the highlands until they became hell on earth.

But is Virginio right in his stance, in how he insists on dragging Sisa down with him? More impressive even than Utama's visual grandeur and folkloric idiosyncrasies is its sense of moral ambivalence. Grisi's script asks us to sympathize with Virginio's worldview while also holding on to the possibility that he's wrong. Maybe living would be the maximum expression of respect to those who came before, perpetuating tradition outside dogmatic limits. Maybe freedom can exist in compromised conditions, as long as defeat isn't passively accepted.

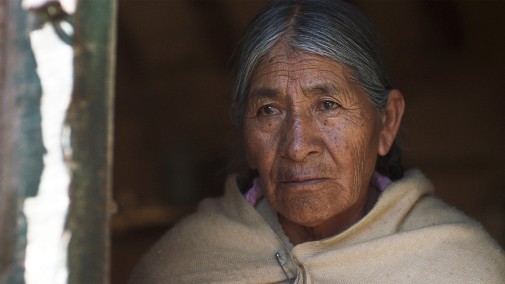

If Clever commands the movie's barebones plot and Virginio's subjectivity dictates its guiding aesthetic, then Sisa's heart is the picture's troubled soul. And thus, Grisi finds the most extraordinary landscape of them all. Not the arid expanse and the river's line but the human face. In Luisa Quispe's solemn sorrow, the camera finds the deepest mysteries of Utama, its unforgiving truths, and beautiful revelations.

Utama won the World Dramatic Competition at Sundance. You may still be able to catch screenings of the film during the weekend.