With Cyrano in cinemas at the end of the month, Peter Dinklage is on the hunt for his first Oscar nomination. Playing a musicalized version of the classic role, the actor can capitalize on his stardom, which has been steadily growing over the past decade. After years of being ignored, Dinklage's stint in Game of Thrones made him a household name, beloved by the industry and with a slew of trophies to show for it. Will an Oscar nomination be next? It's the second time he's seeking Hollywood's most coveted statuette, having also been a contender back in 2003. Tom McCarthy's The Station Agent was Dinklage's breakthrough, an indie gem with incredible acting across the board…

The Station Agent tells the story of Finbar McBride, a taciturn man with dwarfism and affection for trains, railroads, their history, their motion. He works in a New Jersey train model shop when we meet him. It's a small place, owned by a kind older man who's also our protagonist's only friend. When he dies, Fin inherits an abandoned train depot in Newfoundland, and, searching for seclusion, he moves there. However, the grieving fellow finds company in new friends who walk their way into his life, whether he wants it or not. There's Emily, the local librarian, and Cleo, a young girl who shares some of Fin's passion for trains. But, of course, the most vital connections are with Joe, a Cuban guy operating the snack truck that sits by Fin's door, and Olivia, an artist haunted by her son's death.

For Peter Dinklage, Finbar's early scenes represent a case study of how to play an introverted person. You see, acting introversion can often present a performer with nasty pitfalls. It's easy to do too little, internalizing one's characterization to such an extent that the camera captures nothing but muted neutrality. Though some find fascination in the inscrutable, these approaches are dull to watch. The other common mistake is to do too much, externalizing the internal through such mannered mechanisms that a character's essence gets lost in actorly tricks. Add other elements such as grief and stubborn solitude, and you get a role that's a bit like a trap, a film akin to an actor's minefield.

The key to solving the problem is a good sense of specificity. Natural charisma also helps, and, thankfully, Dinklage has that in spades. Even at his most downbeat, the actor's a welcome screen presence. As Fin, he's tired, exhausted, driven to disdain towards a world that, every day, presents him a barrage of humiliations, so regular to the point of being routine. Walking down the street, insults erupt from the mouths of rude kids. At the supermarket, a cashier might not look down to see him, provoking an episode that leaves everyone involved choked up on awkwardness. There's a lived-in quality to how Dinklage plays this side of Finbar, illuminating the eroded surface of his selfhood rather than the new excoriation.

In short, he acts as if this man has lived through all of this countless times before. We can see the insults hurt him, but we can also get a grasp of his thick skin accrued over the years, a survival method rather than a personality trait. He doesn't want to be looked at, his countenance denouncing how much it irritates. It bristles to be the center of attention simply by existing. From these torments grows disconnection, depression.

Obviously, depression can be depressing on film, but McCarthy and company find ways to circumvent that perfunctory fate. Mostly, they do this by appealing to humor, sometimes from the gallows, sometimes from a less despairing place. The first interactions between Finbar and Olivia are especially hilarious, as the woman nearly runs him over twice in the same day. The bemused grumpiness that Dinklage exudes when he sees the damn car coming his way for a second time is comedy gold, almost as if Fin is about to laugh at the bizarre predicament.

And yet, that humor never overwhelms the delicate character study. Upon their third, less hazardous meeting, Dinklage has retreated into Finbar's fortress of solitude, playing each gesture with a shadow of suspicion. He doesn't trust her – why should he? Even so, a magnetic link comes alive between those two, born out of her intimate confessions – spoken out in a mixture of mortification and pent-up sorrow – and his palpable, though self-denying, need for connection. Furthermore, Dinklage's chemistry with Clarkson is distinct from his vibe with Cannavale.

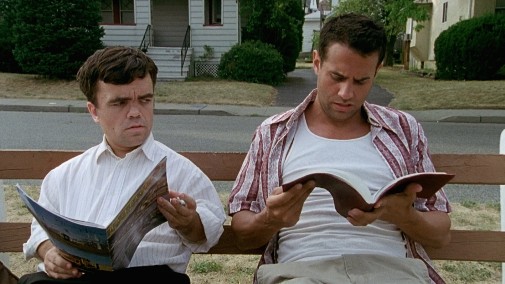

Both work on a level of recognized yearning, but, while Finbar regards Olivia with curiosity, his reactions to Joe tend to read as annoyance melting into an endearment. No actor from the central trio ever sands down their characters' rough edges, their prickliness. Indeed, they depend on them to find hilarity in misery, the inspiration in an unlikely friendship. Notice how, as the two men become close, train-chasing to their hearts' content, new realities flower within their characterizations. Cannavale finds quiet subtleties in Joe's bravado. Dinklage, for his part, allows Finbar to open up, alleviating his suspicious gaze, letting smiles burst through.

It's exhilarating to see the dark clouds lifting, the sun shining from within, warming up the screen, even as the complicated coldness never entirely goes away. When Finbar starts making jokes, it's funny and moving, a tearful laugh expertly evoked by Dinklage and passed on to the audience. His eyes, too, spark with intelligence, an attentive gaze that's always taking in information even though his body language tends toward stillness, his verbosity towards the non-existent. But, of course, when faced with children, they fill with the uncomfortable panic of an adult who's not used to dealing with kids.

On the opposite end of the emotional scale, a short monologue about Fin's unexceptional self, how he's a simple and boring person deep down, is some of the most riveting work in Dinklage's career. For someone who'd become famous for delivering some of the most grandiose monologues on TV with all the pomp and circumstance they entailed, the actor chooses to underplay it here. Thus, he never betrays Fin's insularity, the man's difficulties opening up. Each revelation manifests as a delightful eye-opener for him and us. It's that fantastic trick of making scripted words seem spontaneous, rooted in the moment, in an erstwhile emotional state that's as quick to appear as to evanesce into nothingness. Human connection is precious but fragile.

Because of that, sudden separation is all the more unbearable. Nevertheless, no matter what happens, the effects of their friendship persist, as Fin grows able to reveal himself to others, to step back from humiliation without simmering in its darkness- None of the filmmakers is interested in finding easy resolutions or closure, but that doesn't mean catharsis is off the table. Even a liquor-fueled breakdown feels like a promising development in that it showcases a confrontation with one's innermost anxieties. That being said, the grin that flashes across Dinklage's face at a moment of potential annihilation is devastating, a naked expression so raw it still oozes blood when pressed.

For his first big break as a leading man, Peter Dinklage got sterling reviews and various mentions from critics' groups. Still, at the end of the season, his most important honors were a couple of SAG nominations – for leading actor and ensemble – and a Film Independent Spirit Award nod. At the Oscars, though, Dinklage was ignored. Instead, the Academy picked Johnny Depp in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl, Ben Kingsley in House of Sand and Fog, Jude Law in Cold Mountain, Bill Murray in Lost in Translation, Sean Penn Mystic River. After a contentious and highly competitive Oscar race, Penn took home the first of two statuettes. To this day, Dinklage has never been nominated by AMPAS, though he's found great success with TV awards thanks to his portrayal of Tyrion Lannister in HBO's Game of Thrones.

The Station Agent is available on Showtime and to rent on various services.