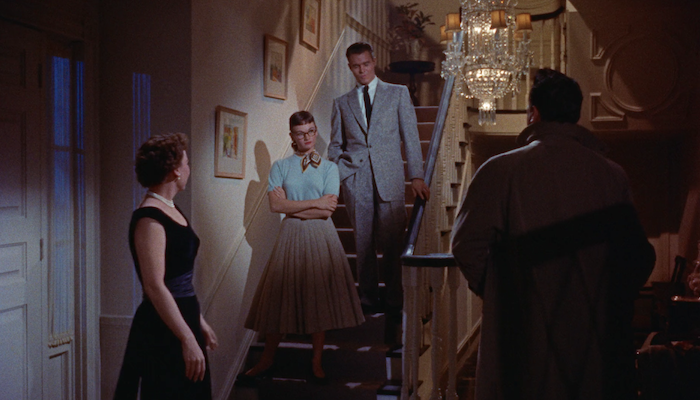

We revived the long dormant "Hit Me With Your Best Shot" club last week with Nightmare Alley and tonight the film is Douglas Sirk's melodrama All That Heaven Allows (1955). It's currently streaming on the Criterion Channel and HIGHLY recommended. The drama features Jane Wyman as a New England widow and Rock Hudson as the younger gardener she falls for. He doesn't care much for societal expectations but she's awfully concerned about what her neighbors and grown children think. While the film was underappreciated in its time (zero Oscar nominations for this beauty?!) it has since grown into being an influential classic, famously homaged in Far From Heaven (2002). (Each week on Best Shot anyone who would like to join is welcome to post their choice for the chosen film. We'll add more shots if any more come in.)

Click on these "Best Shots" to see why these players chose it...

9 PARTICIPANTS

from Jason H at The Entertainment Junkie [FULL ARTICLE]...

from Intifada... [GALLERY]

from Ryan on Twitter... [THREAD]

from Keisha at Cinema Cities [FULL ARTICLE] ...

from Working Stiff's tumblr... [CAPSULE]

from Alexander Georgakis on Twitter... [THREAD]

from Ben Miller at Ice Cream For Freaks... [ARTICLE]

from Nathaniel R at TFE [FULL ARTICLE]...

and from our own Cláudio Alves...

I read about Douglas Sirk before I saw any of his films. Such are the ways of all budding cinephiles, discovering those canonical masterpieces and artists while carrying the weight of great expectations born out of history, legacy, academy. Perhaps because I encountered him after widespread critical reappraisal, I went into my first Sirk film believing it would be a voluptuous melodrama, brimming with conservative aesthetics and a subversive undercurrent subtle enough to go unnoticed until after the director's death. Well, subtle it is not.

"All That Heaven Allows" was the first Sirk film I ever watched, and to think anyone would describe its ruthless vivisection of Eisenhower-era suburbia as subtle seemed ludicrous right from the start. Indeed, it feels awfully condescending to imagine that contemporaneous audiences weren't aware of the picture's intentions, its open disgust towards stifling traditional values even as its milieu is that of the All-American soap opera, all gossip and desperate housewives. The text is pretty obvious in allegiances and condemnations, but beyond that, every formal choice points towards the internal rot of a society obsessed with perceived normalcy, repressing itself into oblivion.

Revisiting the flick to pick a best shot, I knew my choice before pressing play. However, I was surprised by how dark the cinematography is, contrasting its saturated hues with deep shadows at every chance. The story of a wealthy widow falling in love with a younger man and being judged for it isn't necessarily shot as a narrative of suburbanite intrigue and pastel romance. Instead, Sirk and DP Russell Metty fill the screen with horror movie-ready darkness, expressionistic swaths of black that threaten to swallow the leads. The best shot marries these lightless voids with All That Heaven Allows' other visual leitmotiv – reflections and frames as prisons of the self.

This image of Jane Wyman's Cary trapped in the lifeless gaze of a TV set's screen, a black mirror, is the epitome of Sirk's 50s melodramas. It's maybe the best shot in his filmography. It's probably one of the greatest in all film history. Not because of its subtlety but because of the bluntness of intention. It's a punch, a strike, an unwavering scream of anguish crystalized in a frame. If you stare into the abyss, the abyss stares back at you.

thank you so much to all who played along

NEXT THURSDAY: Francis Ford Coppola's Oscar-nominated paranoid thriller The Conversation (1974) - Streaming on Criterion Channel