We're celebrating each of the upcoming Honorary Oscar winners with a few pieces on their career.

Liv Ullmann garnered her second and final (to date) nomination for her role as Dr. Jenny Isaksson in Face to Face, her seventh collaboration with Ingmar Bergman. Last included in the Oscar conversation in 1974 but was hampered by the eligibility issues of Scenes from a Marriage, Ullmann came back in the awards race roaring, with Best Actress wins from NYFCC, LAFCA, and NBR while getting nominations from the BAFTA and the Globes. While Faye Dunaway was the expected winner for Network, Ullmann undoubtedly gave one of her best performances (in a career filled with them) in this film.

TW: Sexual violence/rape...

Face to Face is not considered as one of Bergman’s best works and for a good reason. The film tells the story of a psychiatrist who suffers from a mental illness. On paper, the film comes off as two-sided: the premise does feel overly ironic to the point of contrivance, but it does leave a lot of room for psychological expiration for Bergman and Ullmann. While Bergman tries to infuse the film with interesting choices, it ultimately falters in its own way.

Fortunately, Ullmann is up to the task of creating a character with complete cohesion despite its psychological complexity. It’s a performance so meticulously crafted with each emotional beat fully realized, serving as the building blocks of the horror that will come. Also a thing to note: while all of her collaborations with Bergman afforded her with equally powerful performers to act with (most notably Max von Sydow), this is the first time where the responsibility of carrying the film lands solely on her shoulders. Perhaps due to her longtime collaboration with Bergman, Ullmann already has a mastery of his cinematic language that even at the film’s worst tendencies, her performance was able to shine.

The film begins with Isaksson in a modest state. Her reserve, even her grandmother making her sleep in her teenage bedroom, points to someone who is either being infantilized by her environment or actively putting on that facade. Bergman already plants hints of childhood trauma, but Bergman subverts these on-the-nose visual devices and decides to keep it internal. Ullmann calibrates these moments with care; these early scenes already have an undercurrent of tension that belies the calm. But the question remains: why is it her instinct to please and appease people around her?

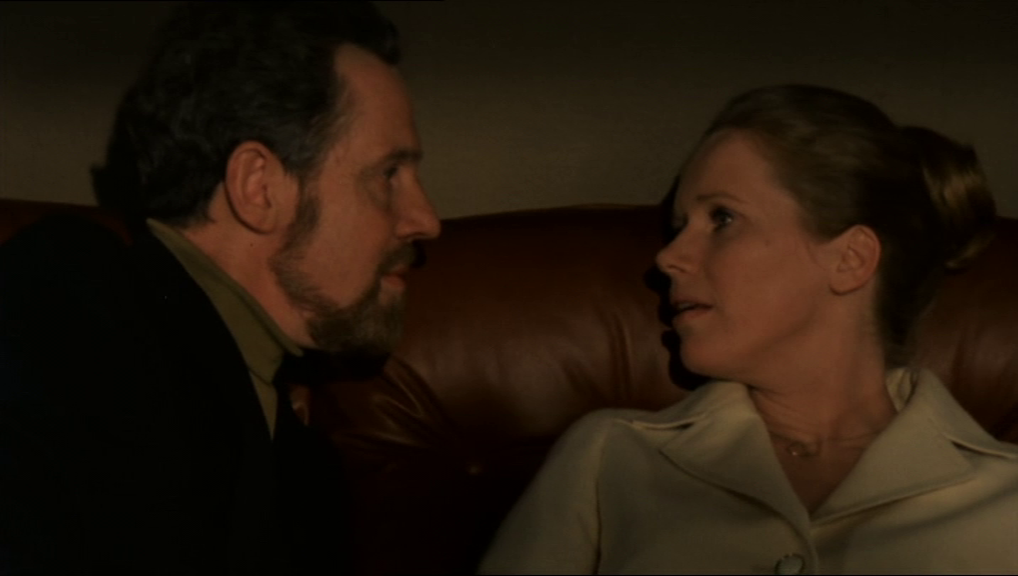

That comes to a halt in a deeply uncomfortable scene with Tomas (Erland Josephson), a doctor that he met at a party. As he starts to flirt with her, she becomes abrasively direct with sex to the point of rejecting his advances without him even offering sex. Ullmann unpacks this moment with subtle gestures and a command in her voice. She turns the tables and makes this moment from an act of flirtation to pure power play. But that even is doubtful: was she intentionally making him uncomfortable just because or did she misread the entire conversation?

We clearly see the latter, but what is more interesting is the room for doubt that Ullmann explores. perhaps the first moment where we overtly see the darkness of her sexuality. We see her but we do not really know her. But this does not muddle her characterization. Ullmann is using these moments to steer us into even engaging with her more. This is also a setup to what is going to happen next. Another question comes up with her character: what is her relationship with sex?

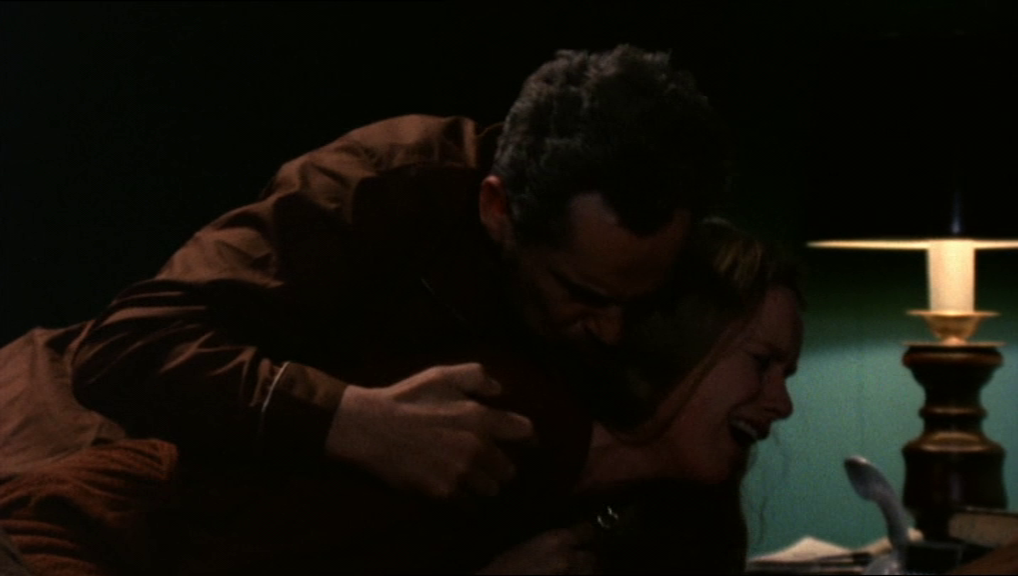

In a pivotal scene, two men break into the mental hospital and rapes one of her patients. She was almost raped too, but the attempt failed. This moment is visually strategic. Bergman refuses to let us see what was happening to Isaksson, filming the scene with a wide shot in a long unbroken take and with Ullmann mostly obscured from the camera. That does not make this moment any less merciless. On the other side of the frame, we see the patient already attacked. As an observer, we are helpless. With her face either far from the screen or dimly lit, Ullmann is physically present yet almost catatonic. Her shock is startling and palpable. This moment even furthers the complications that will unfold from hereon.

Later, Isaksson experiences a breakdown and confesses to Tomas that she wishes the attackers succeeded in raping her. From stoicism to laughter to outright breakdown, an explosion of clashing emotions ensues. To delve into the messy emotional aftermath of the attack is a bold move from Bergman. We see Isaksson try to sort out her emotions, albeit one that probably ended with more damage. Ullmann faces this scene head-on and dares to plot these beats with haunting clarity. Out of a moment that might have been trivial in the hands of a less skilled person, she finds the truth in it. While this scene feels very exposing, this is just yet another puzzle piece that Ullmann lays out in constructing this deeply troubled character. The preceding scenes of her being treated like a child complicates it even further. Does she really mean it when she said she was actually raped? Or is it a misconstrued expression of sexual frustration?

As Isaksson goes on a downward spiral, the film starts to employ nightmare sequences in extended sections to depict her psychological demise. While initially promising, the decision to use extended nightmare sequences to unspool Isaksson’s mental breakdown became laborious and overindulgent, as if Bergman had lost control of his own creation. They just feel superfluous, especially given Ullmann’s face that is expressive enough to illustrate her character’s turmoil. But still, Ullmann rises to the occasion and maximizes these moments. She gets a lot of closeups while externalizing the deep-seated emotions that we did not see beforehand.

In the climactic scene, Isaksson experiences a full-on breakdown as she recounts her past and unravels in real-time. Ullmann reaches for the depths of her character and excavates trauma, with moments where she even imitates several people from her past that may have contributed to her current mental state. Ullmann is exhausting to watch here: with her body language almost itching to be freed, her voice transforming from one person to another, her piercing cries bellowing right in front of us. Rarely do we cut away from this moment. Bergman does not let us escape from this psychologically claustrophobic moment. We stay with Ullmann’s face and we are left with no choice. All past questions faced. Trauma being confronted. Internal struggle externalized. A harrowing moment to witness, terrifying even, but nonetheless a captivating one.

Ullmann’s work in Face to Face is astounding, one that showcases not only her mastery as an actor, but her generosity as a human being in exposing herself in this manner. It is incredible how she managed to turn this film from an artistic exercise to a challenging exploration of mental illness. This is the second time that I have seen this film and my appreciation for her work continues to grow. And that is Liv Ullmann’s gift to filmgoers. She dared to go to emotional places that not even the rest of us would be willing to. Or to those who have already been there, she rises to the occasion, takes on these roles, and manages to give a face to the complexities of the human experience through the different characters that she has played.