To celebrate Doris Day's Centennial we're watching a few of the superstar's movies...

No matter how popular she was in her heyday, it's hard to look at Doris Day's lasting legacy and not think she's a tad underrated. Perhaps not as a comedienne or a songstress, but surely as an actress. Especially as a dramatic actress. While Day consolidated her stardom with many musicals and romantic comedies, her range went beyond such genres. She could as easily make her audience swoon and laugh as she could break their hearts and rile up adrenaline through pure suspense. So as we celebrate the star's centennial, let's appreciate the full breadth of her talents and shine a light on her brief stint as one of Alfred Hitchcock's (not so) icy blondes…

The mid-1950s represented a transitional period for Doris Day. True superstardom was still out of reach, though she'd been working in Hollywood since the previous decade. It wasn't for lack of trying on anyone's part. Warner Bros. had been casting her as their prime musical sensation, and Day starred in many a success. I'll See You In My Dreams broke box-office records while Calamity Jane gave the singer another tuneful triumph, her fourth No. 1 hit single. However, 1955 would see Day become a big-screen actress whose fame wasn't dependent on her singing career. That year, Charles Vidor's Love Me or Leave Me proved her dramatic chops, secured the public's adoration and the industry's affection.

Even the critics sang her praise, comparing her work to some of America's best stage performers. The analogy wasn't without merit seeing as Day truly is a force to be reckoned with in the role of Ruth Etting. Because of its stars and promotional material, Love Me or Leave Me might seem like bubbly entertainment, but the truth is somewhat different. In actuality, the film's the study of a toxic relationship, dramatizing years of abuse between Etting and her mobster husband. James Cagney got a much-deserved Oscar nomination out of it, and Day was probably close to making that year's Best Actress lineup. While that would have to wait until 1959, it was clear that Doris Day was an unstoppable force.

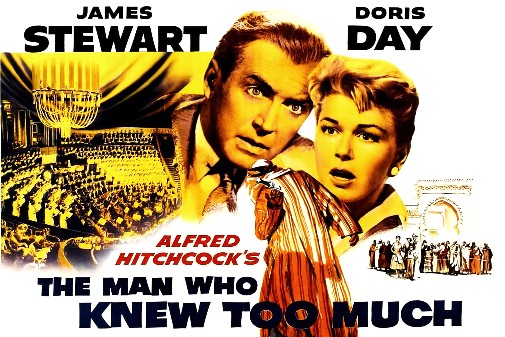

And yet, some still thought of her as a singer unfit for any role beyond musical jest. Such was her reputation as a musical comedy sensation that Alfred Hitchcock had to fight his producer Herbert Coleman when casting The Man Who Knew Too Much. The picture's a Hollywood remake of the director's 1934 movie of the same name. It tells the story of Dr. Benjamin McKenna and his wife, Josephine Conway, a former singer. While traveling in Morocco with their adolescent son, the American couple gets involved in an international intrigue. To keep them quiet about the plans to assassinate the British Prime Minister during a concert, the schemers kidnap their boy leading the parents in a tense pursuit, from Marrakesh to London.

Thankfully, Hitch won the quarrel, casting Day as Jo against Coleman's wishes. The role of a singing star trying to pursue a different life for herself present a curious meta-narrative, reflecting the actress's path out from the confines of the movie musical. In other words, she was perfect for the movie. In early scenes, when everything seems alright, her gaze is full of suspicion. Day keeps the proceedings light and airy, but she complicates the tonalities. As Jimmy Stewart playacts American naivety in his typical "aw shucks" demeanor, she negotiates tension. Their starkly differentiated approaches also create friction that unnerves, paranoia sublimated as a clash of acting styles way before we glimpse our first murder.

Perhaps because her presence suggests bland sweetness, Day's subtlety at playing psychological darkness always feels shocking. There's wrongness in the air whenever midcentury Hollywood's most effervescent screen siren performs gradations of unrest. The effortlessness she radiates in comedies twists itself into something close to naturalism when adapted for a dramatic text. Whether here or in the 1955 biopic, Doris Day feels disconcertingly modern. Indeed, as much as I appreciate Day's late-50s and 60s comedies, I wish she had worked more within other genres. Can you imagine what she could have done with a thorny psychological melodrama? In The Man Who Knew Too Much, she comes close, letting us see the tensions underlying the McKenna marriage.

Jo wants more children, but Ben keeps affably changing the subject when this is brought up, making every conversation a passive-aggressive minefield. Later, they speak of monthly fights and pill-popping tendencies, revealing more of their muffled joylessness. With smiles ever-present, they look like the perfect picture of marital happiness, but Hitchcock and Day repudiate the notion. Instead, they force us to look closer and discover the rot growing under the glossy surface. As the news of her son's disappearance comes out of Ben's mouth, their tensions play out in a more extreme fashion. Finally, Jo succumbs to a catatonic despondence. Sure, Day cries upon the initial shock, but her strategy is proved trickier as subsequent scenes unfold.

Looking at the actress in bed, her eyes vitreous and face relaxed, it's impossible not to feel the despair emanating from the screen, a cold panic that numbs and kills. She never does too much, nor too little, nailing Hitchcock's style on her first try. During shooting, it's said Day grew concerned that her director was more interested in technical matters than what she was doing as an actress. Confronting him about it, Hitchcock simply said, "My dear Miss Day, if you weren't giving me what I wanted, then I would have to direct you!" Looking at the picture, it's easy to see why Hitch had nothing to say to his leading lady. She was perfect.

As the narrative moves to London, Day's a master of underplayed subterfuge, acting out a particular gesture while silently confiding the truth to the camera and, by extension, the spectator. Look at how she fakes social pleasantries with mechanical tightness while her husband tries to make a call about their son's whereabouts. Some performers play interiority by emphasizing the external struggle to keep it hidden. Day, on the other hand, smooths over said struggle. To reveal her character's inner storm, she decides to divide the performance into two faces. One visage is reserved for the audience within the film, her scene partners. Another is only revealed to the spectator off-screen.

In some ways, this is the same methodology that made her such a famous comedic actress, polishing off all traces of effort while negotiating close complicity with her fans on the other side of the screen. Even in the peaks of emotional affliction, one can find a modicum of steeliness within Day's characterization. The first post-kidnap confrontation with the woman who took her son is a non-verbal wonder. Hitchcock frames her and Stewart in the same shot, once again creating unease out of their mismatched styles. He fidgets and demonstrates Ben's tension. She stands perfectly still, her gaze inflexible, an unwavering flash of accusatory blue. Magnetic, Day grabs the audience's attention and never lets it go.

As the movie's climax slowly approaches, The Man Who Knew Too Much bleeds out of words, leaving its leading lady bereft of her most trusted tool. Still, though robbed of her angelic voice by Hitchcock's murderous music, Day excels. Her voiceless terror is, in itself, a rhapsody of expression that proves that, in another life, Day might have been a fine silent movie actress. Jo reacts according to motherly despair, but there's more to it still. Like Kidman in Birth, the actress lets the music reverberate through her, becoming one with it until there's no difference between Jo's plight and the concert's thundering spectacle. At its apex, Day becomes an element of pure cinema, her scream the perfect finish to one of Hitchcock's most extraordinary feats.

However, the climax is not the end, not in this movie. After the assassination attempt fails, the McKennas still have to retrieve their child. In the script's own words, Day is asked to provide "a tranquil coda to conclude a dramatic evening," distracting a room of diplomats in a final attempt at rescuing her boy. And so, Doris Day sings the biggest hit of her recording career, the Oscar-winning "Que Sera, Sera." It's a soft lullaby, a children's song delivered to perfection by the star who shapes it into a hymn of maternal strength. It's the ideal ending to what, in my mind, remains Day's crowning achievement.

You can currently rent The Man Who Knew Too Much on multiple platforms.