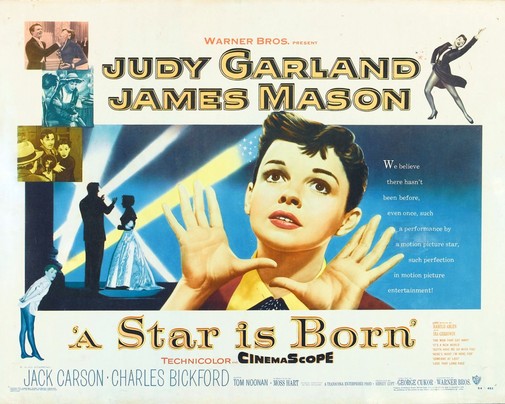

Team Experience is revisiting nine Judy Garland movies for her Centennial. Here's Cláudio Alves on the star's first Oscar nomination.

A Star Is Born is Hollywood's favorite legend about itself, a mythic middle point between propaganda and self-critique filmed four different times from the 1930s to the 2010s. Five, if one considers George Cukor's What Price Hollywood? since that was likely the basis for the '37 version. Though flexible, the story remains mostly unchanged throughout its interpretations. Norman Maine, an alcoholic star on the decline, meets Esther Blodgett and immediately falls in love, with the woman and her undeniable talent. Opening doors for her in the entertainment industry, he watches as she's rebaptized Vicki Lester and rises to the top, far surpassing him. After their wedding and an awards night, whereupon Norman ruins Vicki's moment, she considers giving up her career to take care of him. Realizing this, he kills himself, intent on saving his beloved from his downfall.

Though every A Star Is Born has its merits, the 1954 musical tends to be the consensus pick for the best iteration in no small part due to Judy Garland's performance in the titular role…

First, let's get most of the off-screen misery out of the way. The production of A Star Is Born '54 was a nightmare that effectively sentenced Judy Garland's Hollywood career to a premature conclusion. At the time, she had been ditched by MGM after decades of systematic abuse at their hands, including getting her hooked on various substances, destroying her self-image, and overworking the girl to inhumane levels. Though they were to blame for what Garland became, continuing to employ the star was proving financially unsustainable. 1948's The Pirate saw behind-the-scenes suicide attempts and was the first Garland vehicle to lose money. Then, as her health deteriorated, the studio had to replace Garland in three major productions. That, combined with the number of delays she caused, made it so that even box-office hits like Summer Stock couldn't recoup their inflated costs.

From a teen Vaudeville veteran to the fallen queen of Hollywood, Judy Garland was looking for a comeback when George Cukor's A Star Is Born started being planned. Warner Bros. was hoping that they could capitalize on her erstwhile popularity, promoting the star's return to movie screens after four years away from them. The production's initial troubles were unrelated to its leading lady, mostly centered on the new Cinemascope technology and disputes about the movie's tone. However, it quickly became apparent how difficult it was to deal with Garland's erratic antics. Cukor called his perpetually late, often intoxicated, always exhausted star unhinged and hard to sympathize with. Even after the shoot was complete, the problems kept coming.

Originally running over three hours, A Star Is Born was cut and recut, mutilated beyond belief to the point where some released versions muddled character motivations and story points. To this day, the movie exists in a bastardized form with many sequences made up of original audio running over production stills. Coming back to its troubled actress, A Star Is Born faced a promotional conundrum with Garland unable to do her share of work. With everything accounted for, it was one of the most expensive movies ever made, so, despite its popularity, it failed to generate any profit. Still, immense critical support pushed it to Oscar glory, netting six nominations overall. Judy Garland was the favorite to win Best Actress and was ready to do so even if she couldn't attend the ceremony. A camera crew waited for her acceptance speech by the star's hospital bed.

But of course, she lost. Grace Kelly was the one honored with the Academy Award, taking it home for her deglamorized efforts in The Country Girl. The industry's statement was clear – between the difficult star who kept losing them money and the new 'it' girl racking up the big bucks, they preferred the latter. Who can blame the voters? Well, I can, and so did several people back in 1955. Groucho Marx famously called her loss "the biggest robbery since Brink's," while Hedda Hopper speculated the final result had been historically close. In the end, the scene when Vicki Lester wins the Oscar was the closest Garland ever came to winning a competitive Academy Award - one of many painful ironies in A Star is Born '54.

During the shoot, Cukor pushed his actress to mine personal experiences, understanding that, when talking about Norman Maine's struggles with addiction, Garland was, in essence, talking about herself. It's thus relatively easy to reconsider the film as an ironic confession, both on the part of the industry that destroyed Garland and the woman herself. Yet, such straightforward readings rob the movie and its leading performance of their true complexities, their astounding qualities. To describe Esther/Vicki as the opposite of its performer and Maine as the truth beneath her persona feels cruel. It's also wrong.

If anything, the role represents Garland at her hard-working peak, a woman consumed by the need to entertain. She was also a star born to a different name than what she saw celebrated on the silver screen and movie marquees. That's one in a galaxy of connections between Vicki Lester, née Esther Blodgett, and Judy Garland, née Frances Ethel Gumm. Looking for a generous interpretation, one can say she is the best of Garland's professional history and none of the bad, indestructible instead of broken. More than Maine, Vicki and Judy are distorted reflections of one another. That's true in ways that 1954's Hollywood was aware of, and in ways it was blissfully ignorant.

Furthermore, the part allows the camera to document all aspects of Garland's screen persona and actorly approach. Every technique, trick, tic, and crutch are put to the test and on display, whether explored with loving adoration or twisted into transgressive versions of themselves. Going further still, by the end of A Star Is Born's indulgent duration, one feels as if they've seen Judy Garland play every permutation of humanity. She offers a sampling menu of all that Old Hollywood screen-acting had to offer, from funny one-liners to physical comedy, from a chanteuse's lovelorn sighs to a grieving woman's living hell. It's a Herculean effort, so much performance you feel squashed by its grandeur.

And yet, one shouldn't lose sight of the specific marvels within Garland's creation or the movie proper. While it's easy to be overwhelmed by such majesty, these achievements deserve appreciation beyond generalist praise.

For example, it's important to note that despite its musical glitz, every number in A Star Is Born '54 is diegetic, grounding the fanciful stylings in a realist register. Indeed, this dynamic subverts the precepts of what a big-screen musical was meant to be at the time. Instead of working as escapism, the movie is a tragic romance that befits (then) new trends in psychological storytelling. Rather than presenting a blissful fugue into a Hollywood dream, A Star Is Born is nightmarish, both a vivisection of the entertainment industry and the autopsy of a doomed romance. Nevertheless, it wants to have it both ways. The filmmakers and the characters themselves never stop celebrating the machinery of gilded lies, those celluloid illusions preserved by the blood, sweat, and tears of those who sacrifice everything for show business.

Notably, Esther's first significant on-screen action is to try her damned best to save Norman his dignity and keep the Tinsel Town façade going. So there she is, observing the drunk star making an ass of himself, a sly smile revealing rueful amusement. Adapting choreography to rescue him from the spotlight to backstage, her problem-solving is on full display, as is a sense of quasi-unconscious nerve. As soon as she gets away from the audience's eyes, look how Garland plays Esther's surprise at her own cold blood, that famous shy giggle manifesting for the first of many times across A Star Is Born. Norman is instantly fascinated, following the singer into the dark of a nightclub at closing time. There, he witnesses the full bloom of her powers. He falls for her, so does the camera, and so do we.

Presented all in one take, "The Man That Got Away" starts with Garland downplaying Ira Gershwin's lyrics, foregrounding the camaraderie between musicians after hours. Slowly, she dips her toes into the words' suggested emotion, looking simultaneously like a cerebral thespian trying to forge sentiment and a singer genuinely overtaken with longing. As the number advances towards its full crescendo, Garland negotiates the ever-shifting focus of her performance, playing up to the camera while adding little annotations where she breaks the spell and connects with her bandmates. At certain moments, it's like Esther can't quite believe such a big sound can come out of her petite frame and fragile demeanor.

It's a push and pull – one second, Esther's on the verge of tears. The next, she's smirking and winking, pleased at her showmanship and allowing it to exist in a wavelength of self-awareness. The puzzles and miracles of cinema about cinema coalesce in Garland's thrilling songstress, a perfect crystallization that's still far from her best scene in A Star Is Born. It's enough to take your breath away and restore your faith in motion pictures, even as it breaks your heart and steps on the pieces for good measure. More importantly, it reveals unspoken truths about Esther as an artist. It's not that she wants to perform - she needs to. The song illustrates this tantamount principle, and, because of it, her abandonment of longtime companions to follow an alcoholic's rambling assurances doesn't feel that selfish. How could it? It's like the choice between life and death. She chooses life.

Garland could be an over-demonstrative actress, but she was able to deliver disciplined shows of contention, holding back beneath placid pleasantness or a song's superficial beauties. A Star Is Born is a study of how and when to deploy unvarnished rawness, deploying the fireworks at precise points in the story and never too soon. Dealing with a drunken Norman, quitting her gig, and facing how much the movie industry finds her visually inept for stardom, Garland never indulges in self-pity. Instead, she handles each disappointment with fair bleakness, enough to make us feel for Esther's plight without letting it overwhelm the picture. Her nervousness is subtle, the shadow in the corner of a smile, the tremulous ring when speaking self-critiques. As a result, we never feel she's at risk of being broken by the system.

Look no further than the scene when Esther becomes Vicki. Repeating her new name with three different readings, it's as if we're watching her ponder how it tastes on her tongue. Going from revulsion to resigned determination, she gets over it in no time, and Garland takes us through the entire thought process. There's sturdiness to this woman, a backbone of steel acquired over many years, though it's not an overbearing quality to the point it muddies the potential for frailty. Esther signed up for all of this, clearheaded and reasonably lucid. She wants it and is willing to do the dirty work. It's as if Garland decided to repudiate notions of innocent corrupted, privileging maturity rather than naivete.

That same refusal to drown in melodrama follows her into Norman's downfall and their perilous union. Garland adamantly keeps her distance from whatever notions of victimhood the audience might want to project unto her. Indeed, for a characterization that culminates in heartbreak, the actress seldom plays the blossoming of romance as something especially magical. The attachment between Vicky and Norman is gradual and demanding from the word go, each actor playing courtship like a game of awkwardness and cautious acquiescence. She's charmed but wary, fully conscious of the fickleness of an addict's love while wanting to believe his golden promise. A woman giving in to hope, Garland lets us see how much Vicki's allowing herself to get intoxicated by Norman, her sentimental sobriety slipping. He's drunk on liquor while she's getting drunk on him.

"He saw something in me nobody else ever did. He made me believe it too." When first meeting Norman, Garland's Vicki is someone who used to be a dreamer but learned the hard way that dreams are the privilege of a few lucky bastards. Defeated, she's reborn under his affection, a phoenix rising into the heavens of celluloid, celebrity, and golden trophies. Vicki doesn't necessarily love Norman because he made her a star. She was a star all along. Garland's creation loves her man because of what she saw reflected in his adoring eyes, how he recognized something inside her and never wavered in that certainty. She loves him because, in a vaguely twisted way, he's her best spectator, maybe her biggest fan. In A Star is Born, there are times when it's almost as fulfilling to watch James Mason reacting to Garland's show-stopping numbers as it is to see them directly.

Not that one would ever want to be deprived of such entertainment. Case in point, consider the "Born in a Trunk" musical interlude, a film within the film that signals Vicki's big break and ascension to Hollywood's higher firmaments.

We're always watching Vicki, not merely Garland disconnected from her character. When we watch a real-life actress playing a fictional performer playing the "Born in a Trunk" starlet, the nesting dolls of performance reveal specific aspects of each one. This is most obvious when watching A Star Is Born after other Judy Garland vehicles. Vicki breaks more easily than her interpreter, allowing her vulnerability to shine through – something that is notoriously absent from most of Garland's work, even when one knows about the horror backstage. If Vicki breaks character more than Garland, the Trunk gal is even more prone to showing weakness, messing up her chorus girl routine with a very un-Garland-like clumsiness.

Still, she's a powerhouse, an instant star. When taking on the parts of dramatized actors, some performers invest so much in the behind-the-scenes work that they forget to take the show scenes seriously. Garland never makes that mistake. Even in peaks of dramatic acuity, every glimpse of Vicki's acting is electrified by Garland, showing us all she's capable of through the prism of another performer's singularities. Furthermore, you can see how Lester gets better at covering her intimate pains with outward glitz. By the point she's having dressing room breakdowns, not a shade of troubled inner-life shines through the perfected showbiz façade. Vicky is learning to compartmentalize as everything beyond the camera's gaze goes to shit. After all, the clown's painted smile is all that matters. As long as the tears don't wash it away, everything's fine.

Speaking ugly truths, Vicki confesses how love isn't enough to save Norman, though, in arrogant self-delusion, she thought it was. Garland reveals how the star hates herself for the failure, but we, the audience, know there's little she could have done. Norman was bound to fall from the Hollywood upper echelons, regardless of Vicki's rise, and nothing could stop his implosion. At most, their respective fates could be delayed – her rise, his fall – but never erased. That's what makes A Star Is Born such a perfect Hollywood tragedy - it's the sense of cosmic inevitability that transcends everything known to Man, love included. In another ironic twist, Garland's freckled makeup and clownish costume serve to salient the gulf between what the camera perceives and the internal realities of those it captures.

Maybe because it synthesizes the film's thesis, the backstage breakdown is usually considered the pinnacle of Garland's performance. However, two other moments rise above it for me. First, there's the Oscar incident and, then, a domestic song and dance number, the last attempt at cheering Norman up.

At the Academy Awards, Garland plays Vicki as if she's excited about the honor but can't stop worrying about Norman, right until he materializes and she freezes. The scene is a collection of brilliant actorly graces, a star's studied elegance colliding with absolute mortification. The moment is made more horrifying by how each actor plays it with a single-minded focus on their screen partner. Mason' Norman is utterly ashamed once he realizes what he's done, and Vicky is paralyzed like someone who recognizes her impotence and is just waiting for the nightmare to be over. Other actresses have played this same interaction with a wife's frazzled despair, but Garland is unique in her ability to keep control when playing someone out of control.

The living room showstopper is equally unimprovable, built entirely on Judy Garland's ability to summon a movie studio out of thin air. On a purely physical dimension, it's hard not to be awed by Garland's athleticism, the muscular verve with which she plows through the song, indicating Vicki's after-work exhaustion and her commitment to the bit. Genuinely funny and terminally delightful, she livens Norman up for a fleeting second, but as soon as the flush of entertainment passes, so does his despondency return. Her incandescent sense of triumph dims into nothing like a candle snuffed out. In the aftermath of a musical orgasm, the reprieve from suffering sours all it touches. It becomes something akin to lemon juice poured over an open wound. Her virtuosity was once a balm, but no more.

Now, it only hurts, for it reminds Norman of what he has lost. Maybe it signals what's at stake were he to drag Vicki down with him. Norman Maine is no monster – he wouldn't dare to deprive the world of Vicki, nor her from the world. But, then, it all ends - with a suicide, a noisy funeral, suffocating grief, and one final iconic line. The words are elementary on paper. Coming out of Judy Garland's mouth, they are insanely complex. "Hello, everybody. This is Mrs. Norman Maine."

One could throw that line away in a paroxysm of grief, but Garland infuses it with pride. Not a timid kind of contentment, however. On the contrary, it's a defiant act in the face of Hollywood's ugliest inhumanities. She leaves us with that note, regaining autonomy over her tale even if, at that specific moment, it means calling herself a wife first, a star second. It also means presenting herself as a stalwart survivor, both of Norman's disgrace and the machinery that got him there. She survived, and she won't let anyone forget it. Will she fade into self-effacing widowhood like some American Queen Victoria? Quite possibly. Or maybe this is just the start of her full glory. We can only hope so. Though, of course, for Garland in Hollywood, A Star Is Born was the beginning of the end.

At last, returning to the Little Golden Man That Got Away, I'd say Garland delivers the best performance ever nominated for an Academy Award and is a good candidate for one of the best performances in cinema history. Apologies for the hyperbole but facts are facts. If this isn't Oscar-worthy, I don't know what is.

You can find A Star Is Born streaming on HBO Max. The classic is also available to rent on many platforms.

More for Judy's Centennial here at The Film Experience:

- The Wizard of Oz (1939)

- Babes on Broadway (1942)

- Meet Me in St. Louis (1944)

- The Clock (1945)

- Easter Parade (1948)

- The Pirate (1948)

- Summer Stock (1950)

Tomorrow: Judgment at Nuremberg (1961)