We're revisiting the 1997 film year in the lead up to the next Supporting Actress Smackdown. As always Nick Taylor will suggest a few alternates to Oscar's ballot.

I’m betting that we (the public, spiritual types, film people, you specifically) have some thoughts about Ms. Goop. Some of these thoughts might be compartmentalized to certain aspects of her career, while others bleed over into a general patina of how one perceives her. We (the writer of this article) won’t and frankly don’t have the time to get into the grifter empire, the nepotism, her instrumentality amongst the many journalists and witnesses who helped to bring down Harvey Weinstein, Bosco’s awful 'Snatch Game', the lazy potshots from Knives Out, or her advice to combat the symptoms of Long COVID using a keto diet as she is currently doing, but know that these thoughts are in the back of our mind at all times when the subject of Gwyneth Paltrow is summoned into a conversation.

There’s plenty of opinions about her that one could have, but for the purposes of this write-up - a tribute of her resourceful, top-flight performance in Hard Eight that’s as worthy of recognition as anyone else in Boogie Nights the same year - let’s keep it simple and state, man, wasn’t she a fantastic actress when she wanted to be?

I doubt there’s any major desire to act even in the back of her mind, and who knows how much she looks back on the decade and a half of ambitious character work she left before devoting most of her time to narrating documentaries and standing in front of green screens for MCU films she can’t pretend to remember she was in. I’ve heard good things about her in The Politician, and maybe it’ll inspire her towards reigniting her film career someday. But all we have for now are the memories of what was, and Hard Eight is a stunningly good reminder of what Paltrow could do when she gave a damn.

By the time we first meet Paltrow, in the role of a cocktail waitress named Clementine, we’re already 20 minutes into Hard Eight. and have watched Sydney (Philip Baker Hall) and John (John C. Reily) meet each other for the first time at a coffee shop in Sparks, Nevada. The two meet when John is penniless, having lost all his money in Vegas trying to win enough money for his mother’s funeral. Sydney takes pity and gives John the tools to work the casinos and earn enough to bury his mother. From this fateful day we flash forward two years to find them lounging in a Reno casino. Sydney loves John like a son, and John admires his savior deeply. Just as Sydney took an interest in John, he’s intrigued by Clementine, who calls him “Captain” and has a mutual attraction with John.

Paltrow rewards that intrigue with a bruised, off-the-cuff moonglow quality that emanates from her like a candle. We quickly get the sense that Clementine matches John’s lack of sophistication, though like Sydney, her outlook and instincts are very much shaped by how long she’s spent hovering in the same place. Working late nights in casinos and moonlighting as a sex worker, Paltrow moves and talks like she’s been doing this for years. She knows how to flirt with customers without seeming insincere, how to give them her attention in a way that makes them feel seen, leaving them flattered and earning her a good tip. Sydney recognizes this, and is initially unsure how much their rapport is a mechanism of her job rather than an earnest bond.

When Sydney asks if she’s required to flirt by the establishment, Clementine responds with dry amusement and undisguised flickers of anger that no, she doesn’t have to flirt with her customers, but if she doesn’t her bosses will reprimand her for being rude and she won’t get tipped. She’s accepted the situation for what it is, which does not mean she is happy with it. Sydney fears being treated like the uncouth men she waits on, and wants to know why Clementine calls him “Captain”. She tells him the name comes from the way he always seems in charge. Sydney trusts her enough to accepts the nickname. Hell, maybe she is flirting with him and found the right way to make him accept it, but Paltrow doesn’t tell. Her apparent sincerity with him goes a long way, and Clementine’s rapport with Sydney (and Paltrow’s rapport with Hall) will remain vital to the film.

Later that night, the two get coffee together at an all-nite diner after Sydney sees Clementine leaving a motel room, her hair a bit messier and her lipstick slightly smeared. Clementine confesses she’s a sex worker, and floats between unpretentious explanations for why she’s hooking and anxiety that this discovery will make Sydney and John think less of her. Clementine’s dialogue is not completely devoid of a self-rationalizing bent, yet Paltrow frames this scene as an extension of the worn-out resignation from their earlier conversation about her flirtatiousness. As Clementine tells it, this is a standard that plenty of her coworkers are participating in to afford living in the city. She doesn’t have to, but she can’t get by otherwise.

Paltrow plays all of this with an immediacy that belies how frighteningly unknowable Clementine is. She doesn’t bother distinguishing Clementine’s on-the-clock or off-the-clock demeanor, and her in-the-moment earnestness is offset by a complete inability to plan things. Clementine gets only one scene where she is completely by herself, sitting and waiting in a bed she assumes is in Sydney’s hotel room for the man to come back. With a numb expression that Paltrow perches at the edge of some bottomless void, Clementine adjusts her outfit, grips the nylon on her right leg like it's a life preserver, and plays with her lips. Is she steeling herself for the question she’ll ask Sydney when he walks back into the room? Does she expect him to say yes? Does she think it might lead to something ugly for her (an ungliness that both Philip Baker Hall and Anderson have avoided in the depiction)? Has she actually calculated his answer, or is she so used to what normally happens in this scenario that she’s stopped thinking of him as a unique individual, now that he’s where other men have stood? Is the question even what’s affecting her, or is it something else entirely?

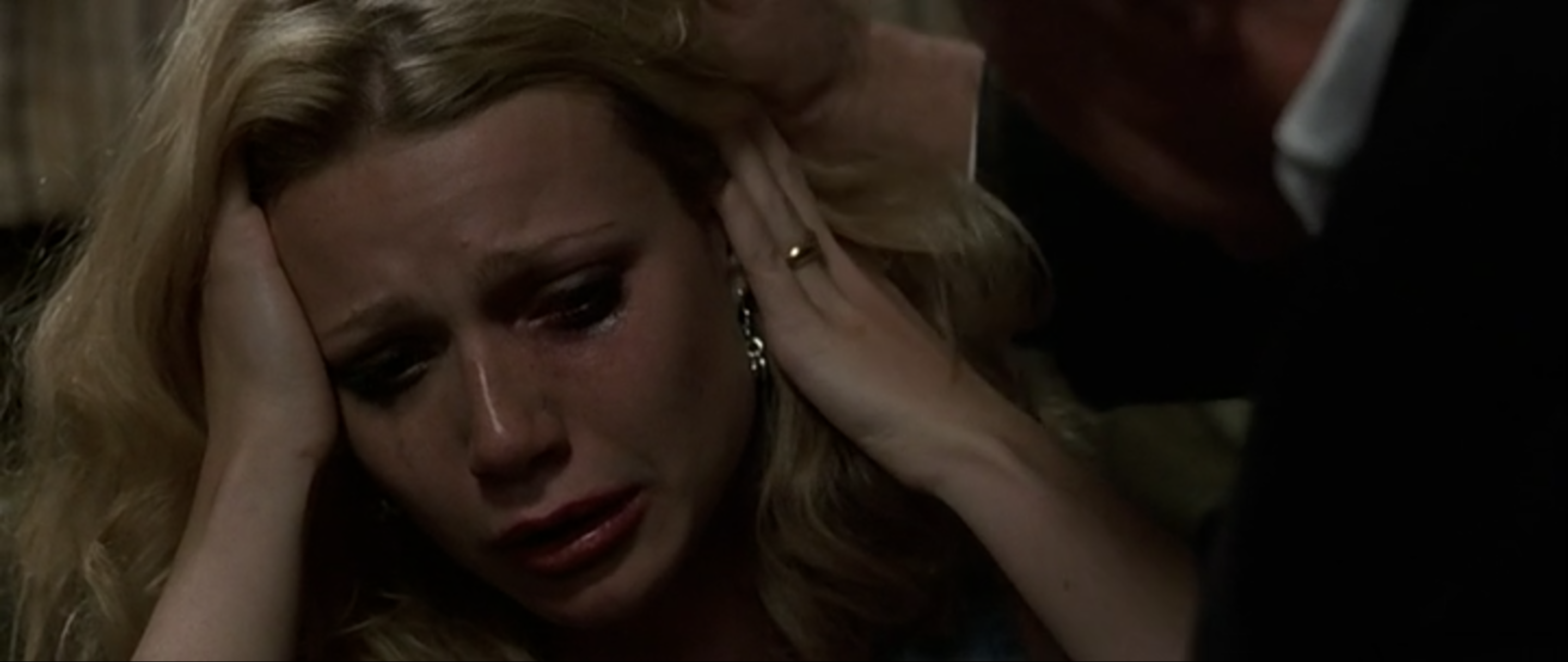

Where another actress might let a host of expressions wash over her face, specifying something about Clementine’s anticipation or revealing the character’s core, Paltrow conveys a sense of emptiness bigger than the moment she’s inhabiting. She refuses to overplay crudeness or alibi impulsive off-screen choices with wild behavior. Instead, Paltrow keeps us at an arm’s length from Clementine, holding firm in depicting her as someone who’s shrunk to survive the life she’s stuck in. When shit hits the fan later in the film, and Clementine is now in possession of an unconscious client and a new husband, Paltrow can’t even hold her head up as everything spirals around her. She sinks further into herself before lashing out at her would-be helpers, desperately trying to scrounge up any control in a horrible situation. It takes Sydney to help her hold her chin up and fight to finally get out of Reno, forcing her to move towards a real future.

Clementine’s goodbye to Sydney and promise to John that she’ll do better, both ring with bleary-eyed sincerity. Yet Paltrow’s final close-up is all about inward-facing contemplation, as if she’s finally safe enough to really start processing her new life. Does she feel happy? Trapped? Relieved to be somewhere else, regardless of how she got here? Is she still paralyzed by the past 24 hours? Does she now have space to grow, rather than shrink? The last shot we get of her is fairly cute, looking up from fogging up a car window and drawing hearts on it to wave at John, but the radical changes in circumstance that happen to Clementine every time she’s offscreen for more than five minutes still creates a sense of anxiety. We believe she wants to be better, but her uncertainty lingers as much as her resolve.

I love the adage that a movie is about the most interesting point in a character’s life. In the case of Hard Eight, I believe this is true for Sydney, whose name was the original title of the film. Clementine, on the other hand, ends the film on an open note of piqued introspection and genuinely new opportunities, and Paltrow plays her so arrestingly throughout the whole film that I would happily follow her into her own film.

For all the things Gwyneth Paltrow is remembered for - and at this point, I’m not sure how many people would or should lead with her bonafides as an actress versus the yonic candles - I hope her era as a serious, challenging actress is looked upon fondly. Her brilliance in Hard Eight is so different from her conwoman’s charm in Flesh and Bone, her painfully carved loneliness in Se7en, her sidelined fury in The Talented Mr. Ripley, and her funny, deeply sad turn in The Royal Tenenbaums. For all the praise her luminous, valuable star turn in Shakespeare in Love received, her knack for communicating such harrowing characters without flattening or valorizing them feels more representative of her portfolio. Even her own yonic candles can’t hold a candle to work like this.

Hard Eight is currently streaming on Hulu and Showtime, and is available to rent on most major platforms.