On this day, 233 years ago, revolutionaries stormed the Bastille, seizing control of the medieval fortress turned political prison, a symbol of royal authority over the people. The event is often thought of as the inciting incident of the French Revolution. This time of radical societal change, which lasted until 1799, represents one of the most critical points in human history, the endpoint to the early modern period. To mark the occasion, since 1790, France has celebrated the Fête de la Fédération, a national holiday commonly known as Bastille Day. As a self-described French Revolution nerd who's been obsessing over the subject since middle school, it's a pleasure to combine that passion with another immortal love of mine - cinema. What better way for a cinephile to celebrate the date?

So, without further ado, let's explore how filmmakers have looked at this chapter in history. There are countless approaches, of course, but I shall focus on ten examples, including THE FRENCH REVOLUTION AS...

…SILENT MELODRAMA

D.W. Griffith was no progressive, so his views of the French Revolution were informed by conservative values. In his Orphans of the Storm (1921), every shade of grey turns into black-and-white morality, and the picture's general message is a bullish demand for cooperation, the status quo forever deified. Thus, it's easy to discern an implicit commentary on the then-new Russian Revolution, adding to anxiety over the new changes of a post-World War I society. Of course, it's all very reductive, showing an infantile understanding of complicated history, but that's D.W. Griffith for you.

To make up for it, Orphans of the Storm is a lavish spectacle, its production values as heightened as the narrative's sentimentality. Moreover, Dorothy Gish is a lovely screen presence in her last film for the director, while Joseph Schildkraut is blindingly charismatic in the romantic hero role.

…OLD HOLLYWOOD STAR VEHICLE

Before his tragic death at 37, Irving Thalberg was MGM's wunderkind, a boy wonder who made the studio into the Old Hollywood jewel we know it as today. At the time of his demise, the producer was in the development stages of a new star vehicle for his wife, Norma Shearer. It was an opulent historical drama about Marie Antoinette, following her from her arrival in France to death by guillotine. Even as her enthusiasm for movie stardom waned, Shearer took her late husband's last project to completion. The result is a resplendent epic heavily informed by Stefan Zweig's biography of the French queen.

Begowned in some of Adrian's most extravagant creations, Norma Shearer delivers the performance of a lifetime in Marie Antoinette (1938), going from girlish innocence to a broken woman facing her end with stalwart grace. Though unsympathetic to the revolutionary cause, the movie's best scenes are found in its later passages, when grand spectacle fades to harrowing human drama.

…FILM NOIR

Like nearly all of the entries in this list, especially the early ones, Anthony Mann's Reign of Terror (1949) is pretty ridiculous as a dramatization of historical events. Nevertheless, the film's a showcase for the director's genius, not to mention the miraculous skills of cinematographer John Alton. The intersection of costume drama and film noir uses the historical setting to stage a tapestry of mounting paranoia, every frame another sublime nightmare of sharp light and inky shadows. Though the leads aren't outstanding, the supporting cast makes up for their lack.

Richard Baseheart is a monstrous Robespierre, Arnold Moss underplays Fouché's machinations to great effect, and Jess Barker is chillingly cruel as Saint-Just. Still, Beulah Bond, of all people, deserves to be called Reign of Terror's MVP. She only appears in a few scenes, but the actress makes a strong impression as a grandma facing off against the questioning of a ruthless officer.

…THEATER OF MADNESS

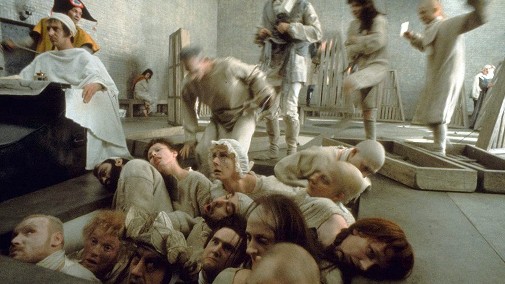

In 1964, Peter Brook directed a Royal Shakespeare Company staging of Peter Weiss's German play Marat/Sade. It's all set inside an asylum in 1808, as the Marquis de Sade stages a performance about Charlotte Corday's murder of Marat. Combining elements of Brechtian expression and Artaud's theories about the Theater of Cruelty, the show proved to be a sensation. Even nowadays, it's taught as a prime example of the 20th-century theatrical vanguard. The piece's transgressive nature reflects its themes, its historical purview of political upheaval, abject suffering, and class struggle, questioning the matter of revolution as change that's both collective and individual.

Three years after that original English-language production, after it had transferred to Broadway and swept the Tonys, Brook took the show from stage to screen. Marat/Sade (1967) is his greatest cinematic masterpiece, the kind of film that belongs in every list of best pictures ever made, not to mention a precious historical document for those who study Theater. Most of the original RSC cast returned, including Patrick Magee as the Marquis and Glenda Jackson as the madwoman who plays Corday.

…NEW HOLLYWOOD COMEDY

No list of French Revolution-related media could be complete without mentioning A Tale of Two Cities. However, one need not be limited to straightforward adaptations. Bud Yorkin's Start the Revolution Without Me (1970) takes loose inspiration from that Dickens classic, mixing it up with elements from Dumas' The Corsican Brothers. From this weird combination, a wild comedy emerges, one that's equal parts historical farce and a parody of the swashbucklers of Hollywood's Golden Age. Gene Wilder and Donald Sutherland star in double roles, playing two sets of identical twins separated at birth by an unfortunate mishap.

Two brothers went on to live as Corsican noblemen. The other pair, au contraire, grew up in squalor, becoming France's most dimwitted revolutionaries. When their paths cross in overlapped conspiracies, hilarity ensues. If anything, the story's mounting contrivance serves as fuel for the comedic fires, blazing in a crescendo until it ends in a meta-cinematic shoot-out. Not all the jokes have aged well, but it's difficult to resist the charms of Donald Sutherland at his most foppish or Hugh Griffith's tasseled take on Louis XVI.

…ROMANTIC FANTASIA

It's time for a confession. I'd like to say my fascination with the French Revolution started as a byproduct of an interest in history or my parent's influence (they both have degrees in history, my mother being a teacher). However, the seed from which this passion spouted was less highbrow. It was an anime called Lady Oscar or The Rose of Versailles (1979-1980), an adaptation of Riyoko Ikeda's seminal manga about the French Revolution, which combines real-life characters with fictional melodrama. The TV series' protagonist is an aristocratic woman raised as a man to be an officer, eventually becoming part of Marie Antoinette's royal guard.

Though it could be called a kid's show, it's probably one of the most politically complex works in this tenner, acknowledging the need for radical violence while contemplating the human cost of such violence. Jacques Demy's live-action feature adaptation of the same manga maintains these same themes and general plot while losing much of the narrative complexity. What can you expect when the anime is around 980 minutes and the film a mere two hours? In any case, they're both good examples of queering history, using fantasy to explore complicated truths.

…SOCIOPOLITICAL HISTORY

If you're searching for the best dramatization of the French Revolution as it happened, then look no further than Robert Enrico and Richard T. Heffron's two-part epic. The French Revolution (1989) is a gargantuan thing, running over five hours in its complete version, with great attention paid to historical accuracy and a multifaceted portrayal of events. It neither shies away from the revolutionaries' cruelty nor villainizes their efforts, extending a humanistic empathy towards every person involved. Mayhap it's not very exciting as dramaturgy, but it's catnip for history nerds such as myself.

Moreover, fashion-wise, this is one of the best depictions of the period from 1789 to 1794 in France, paying particular attention to how style reflects politics and class, personal values, and cultural beliefs in constant flux. The cast is an international marvel, though none of its stars can justly call themselves the protagonist. The French Revolution is far too collective in spirit for that. Regardless, some performers deserve special praise like Klaus Maria Brandauer, Andrzej Seweryn, and Jane Seymour as Danton, Robespierre, and Marie Antoinette, respectively.

…COSTUME DRAMA TRASH

I may think of myself as a discerning moviegoer, but sometimes bad films emerge as guilty pleasures. Such is the case of The Affair of the Necklace (2001). This deeply mishandled costume drama tells a fictionalized account of the scandal involving Marie Antoinette, Jeanne de Valois, the Cardinal de Rohan, and an exorbitant diamond necklace originally commissioned for Madame DuBarry, Louis XV's mistress. The script is a hodge-podge of skewed fact and wild fiction, the casting a clash of great inspiration and incompetence beyond belief. Who thought Hilary Swank was the right choice to play an 18th-century schemer refashioned as a romantic heroine with a traumatic past?

Thankfully, a handful of strengths mitigate the guilt of those with a soft spot for such sudsy trash. First, Joely Richardson is a beguiling queen, playing the character with alienating aloofness and a tragic sense of social myopia. Second, Milena Canonero's Oscar-nominated costumes are a dream of 1780s glamour, while the hair and makeup turn often modernized trends into accurate stylings that still look beautiful. Finally, the film features one of David Newman's best original scores, full of bizarre references that somehow coalesce into a coherent soundscape.

…A MOVING PAINTING

When it premiered in France, Éric Rohmer's The Lady and the Duke (2001) caused a stir. Telling the story of Scottish royalist Grace Elliott during the time she lived in revolutionary France, the film is a harsh depiction of the Terror as seen through the eyes of an aristocrat in peril. Some saw it as a reactionary picture verging on royalist propaganda. Yet, a dryness to Rohmer's presentation circumvents dogmatic advocacy, concentrating on intellectual conflicts and the dramatization of historical facts as derived from Elliott's memoirs. There's no hiding the selfish subjectivity of the protagonist nor how brutal the revolutionary effort could be.

In the end, it's one of the most political depictions of these events on-screen, inviting reflection rather than promoting a closed conclusion. Beyond that, Rohmer's approach is further defined by risky aesthetic gambits, like the use of painted backgrounds into which the actors were digitally superimposed. The effect is startling, further illustrating the action as something distant, as removed from our present as oil paintings hanging on museum walls. I also have to mention the incredible costumes, which reconstruct the 1790s with a historian's eye for detail.

…PSYCHOLOGICAL PORTRAITURE

Benoît Jacquot's Farewell, My Queen (2012) concerns the last days of Marie Antoinette in Versailles. The limited time frame conveys a sense of urgency, rattling unrest that touches on everything, infecting fear as far as the eye can see. The lensing adapts the precepts of 21st-century European realism to a period setting, tarnishing the Versailles splendor with hand-held chaos, crash zooms, and deliberate roughness. This is not a film besotted with the tragedy of fallen royalty. Instead, it's told from the perspective of the queen's reader, a beautiful young woman intertwined in an erotic liaison between Marie Antoinette and her favorite, Gabrielle de Polignac.

Above all else, the drama revolves around unspoken yearnings and power dynamics, asphyxiating circumstances, and psychological acuity. While the taste for realism feels at odds with some design choices, the cast is excellent enough to sand down the film's more overt imbalances. Léa Seydoux is brilliant as the protagonist servant, while Diane Kruger is a thorny miasma of self-centered contradictions in the queenly role. This might be the German actress' best performance, maybe even the most fascinating portrayal of Marie Antoinette on the big screen.

There are many other French Revolution-themed movies and series worth remembering. Consider Wajda's Danton, Renoir's La Marseillaise, or my beloved Marie Antoinette by Coppola. Perhaps next year, I can return with another list to celebrate Bastille Day. Meanwhile, please share your favorite films depicting The French Revolution in the comments.