By Glenn Dunks

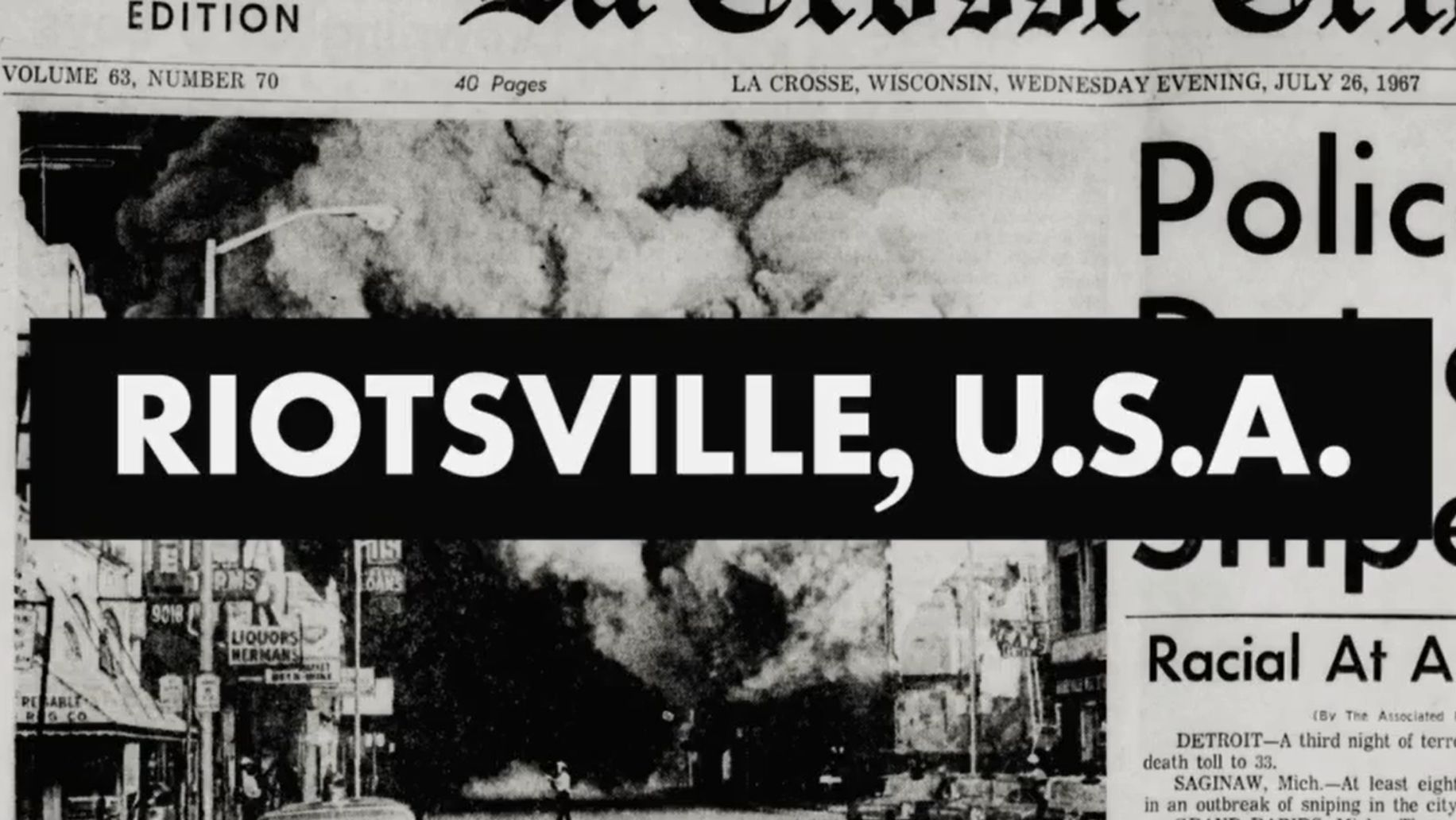

Sierra Pettengill’s Riotsville, U.S.A. begins so strongly. It makes a striking first impression with the usage of an old government film taken of a fake town built on a military base that is being used to train soldiers on how to handle a riot. The entire film, we are informed in an opening title card, will be told using such archival government footage as well as television news coverage. This particular footage is from the 1960s as protest and activism began to take hold of the public, particularly those in predominantly African American communities. In one of the more depressing sights, black soldiers are regularly shown in such footage throughout portraying such (so called) rioters; asked to loot and threaten. The humiliation they must have felt is palpable...

However, like Pettingill’s last film, The Reagan Show from 2016 (another all-archive doc), Riotsville, U.S.A. doesn’t really do much with this fascinating footage. I thought this footage was going to be the introduction to a denser narrative, but that never comes to pass.

After a while of watching this video with interjections from other sources, it ceases to be interesting. Repeating as it does, occasionally with some fairly uninvolving and flatly spoken narration by actress Charlene Modeste. It is a missed opportunity. As I watched, a recalled The Atomic Café and wished for some of the wit in editing of that documentary classic, or just some of its energy. It feels half complete. I kept wanting to ask, well, where’s the rest of it?

There were several of these “Riotsville” townships set up across the country. A stretch of built storefronts on a fake road no longer than a standard city block in any small rural town. These exercises—glass is shattered, whitegoods stolen and put into trucks!—are gawked over by a crowd of old, white men in military uniforms and regalia. Yet again, the saddest such moment comes as a black soldier play-acting at being a protester cries out that his arm is being dangerously winged backwards and we the viewer can’t tell whether he’s really being injured or just very good at performing. The crowd laughs nonetheless. It’s quite a sight.

Such moments ought to build up to something with a bit more to say. But unfortunately, they are dragged out far too long. While additional context isn’t needed to understand what we’re seeing (that much is pretty clear), some sort of historical reflection would have been appreciated. Beyond the narration, anyway. This is a situation where talking heads would really amplify a documentary. Or even voices overlayed to tell us something beyond fairly rudimentary essay. The footage does say a lot. It doesn’t take much to notice the language being used in this footage is similar (if not outright identical) to the same conservative dog whistles of today like “outside agitators” to reference black people and left-wingers. It also doesn’t take much to notice that, yes, instead of spending money on improving equality across housing, jobs and the minimum wage, billions are embedded into police forces to militarize their outfits and riot control to control the masses. They are valiant points, but they’re made quite early on without much deeper exploration.

When the film strays from this type of footage, it finds itself with a bit more vigour to its storytelling. While that of the 1968 Republican National Convention is fairly well known and has been covered elsewhere, it is nonetheless an interesting passage that adds colour to Riotsville’s larger narrative. This is exactly what they trained for and yet. A detour into the publication of the 1967 Kerner Report is among its most fascinating passages. A performance two-thirds of the way through of Jimmy Collier and Rev. Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick performing protest song “Burn Baby Burn” on national television is beautiful. I wanted more of that to build a texture.

Pettengill and editor Nels Bangerter make odd decisions with the material they have got. Why, for instance, is there footage of rockets being fired other than it’s there and I guess they had the material. It seems completely irrelevant. There are moments that are as if extracted from something far more abstract or even experimental, but which appear misplaced. Bangerter especially has been able to craft impeccable films out of archive footage such as he did with Kirsten Johnson’s Cameraperson or Jason Osder’s propulsive Let the Fire Burn. I’m just not sure what they were trying to do here. A really neat short film would have been a more appropriate use of this material, highlighting perhaps the fantasy of the riot in these young male participants, or perhaps reflect on the angry young men of today and those of the Vietnam War era who once got shipped off overseas but whom today are on the internet raging against Black Lives Matter. These are topics that bubble around the edges of Riotsville, U.S.A. but which the movie seems eager to leave as ephemeral.

And none of this is helped by the score, a brooding and sonically murky mix of bleeps and bloops and droning, ethereal whooshing. I see such potential in the material, but I cannot help but feel this is a movie that expects power because of the material rather than anything that it actually does with it cinematically. It’s a film both obtuse and obvious at the same time. It is a polemic that stops short.

Release: In cinemas from Friday the 16th of September.

Award chances: It has proven otherwise popular so I would expect some critics prize nominations, but this isn’t the sort of movie that is typically with the Academy’s forte so a shortlisting would be a bit of a surprise to me.