Killers of the Flower Moon starts in death, but not of flesh or person. The Frontier is no more, the West has been won, and the Track of Tears travailed when the Osage tribe gathers to mourn a way of life. Their traditions, their beliefs, their language are moving into the twilight, so they bury a sacred pipe and give themselves a symbol to weep over and express unsurmountable grief. As if listening to the lament, the earth responds. Black oil bursts from the ground, a geyser of wealth for the People from the Middle Waters brought to this Oklahoma barrenness after settlers pushed them asunder and away from the Great Plains. A pittance place once thought worthless reveals itself a treasure, and, overnight, the Osage Nation becomes the richest per capita population in the world.

So starts Martin Scorsese's latest opus, a title that, even within the context of his hallowed filmography, feels like a monumental achievement…

In rite and Robbie Robertson rhapsody, Killers of the Flower Moon anticipates an opening flurry of archival footage, the most contextualization Scorsese will allow into his epic. After that, talk of headrights, 1920s politicking, white guardianship over Native fortunes, and inheritance laws shall be presented with little to no explanation. It's an all too rare show of respect from a Hollywood filmmaker to their audience's wits. Then again, in most regards, this particular director doesn't want to make things easy for the viewer. After all, for over 200 minutes, he reconfigures the truth of a nation's Genesis and offers his spin on its original sin, showing the white hands that built an empire of spilled blood on stolen land.

With it comes an accusation of complicity, a finger pointing outward from the screen. Not even the comforts of genre precepts will save you from this reckoning, as Scorsese and cowriter Eric Roth have reshaped David Grann's homonymous non-fiction about the murder spree that saw dozens of Osage people dead at the hands of their white neighbors between 1918 and 1931 – a Reign of Terror orchestrated by cattleman and apparent friend of the Osage William K. Hale. Grann's work unveils the mystery by offering incremental clues into the murders, culminating in FBI man Tom White's investigation of a conspiratorial network barely below the surface of polite society.

However, Jesse Plemons's cowboy-like lawman is a secondary figure in this adaptation.

It's so easy to picture the book becoming commonplace procedural that Scorsese's repudiation of the form must be acknowledged as the radical gesture it comprises. There's no occluding of what, who, where, or when. And, to a certain extent, the why is easy to see, plain for all but the most obtuse or naive. The director will rub your face in it, insisting upon the unmasking of this virulent racism that breeds entitlement under the banner of manifest destiny. How becomes the point, turning an American mystery into the quintessential American tragedy. Moreover, by offering the murderers' point of view so promptly, the scheme shocks through its openness.

The obscenities of history feel all the more apparent because, under Scorsese's lens, they operate closer to light than shadow, brazen from the onset.

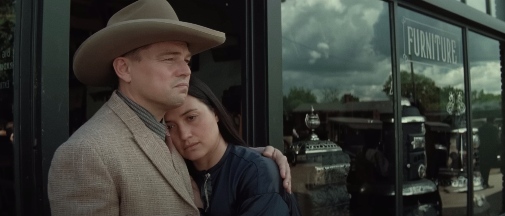

And yet, the narrative doesn't necessarily revolve around Hale's machinations. A mystery turned tragedy, vicious to the bone, Killers of the Flower Moon is also one of the year's thorniest "love" stories. Pivoting from one of the book's least explored figures, Scorsese circles back to the Osage's new status quo in the aftermath of World War I, as Hale's nephew, Ernest Burkhart, returns to the States after serving as a military cook in Europe. Though the real man was an attractive youth untouched by middle age, Leonardo DiCaprio plays him as a stain-toothed remnant of what once might have been a handsome man.

Looking like a weathered Cagney caricature, Ernest's face is perpetually caught in strained and stenuous twists that befit his spirit. Of all the protagonists in Scorsese's oeuvre, he most resembles Kichijiro from Silence and The Irishman's Frank Sheeran, all weak men who should be handled with caution, for they are dangerous despite it all. And so, buffered by his uncle's power, we see him become a driver for hire, crossing paths with Mollie Kyle, an allotted full-blood Osage whom Hale encourages Ernest to pursue. Though the courtship might be prompted by familial pressures, DiCaprio and Lily Gladstone play the growing attachment between the two with genuine affection, complicating our reading of what's to come.

She, in particular, speaks with pragmatic shrewdness about their bond, acknowledging he wants her money while trusting there's a kernel of real love deep within that man with the coyote grin. If not for the advent of violence, Killers of the Flower Moon might have thrived as the study of a loving marriage intersected by greed, shaped by racial inequality and economic disparity. But that's not to be, or, at least, not solely that. In no time, death has spread her wings over Mollie's family. First, her sister Minnie perishes to long-term illness, a fate shared with many others in the Osage Nation. Then, one horrible afternoon, Anna, another sister and their mother's favorite, disappears without a trace.

Soon after, her body is found in a ravine, killed by a shot to the back of the head. More murders occur at a steady pace, a nightmare without end in the middle of which matriarch Lizzie Q. also departs from this plane. In one of the many instances when Scorsese follows the tenets of Osage faith beyond what some might classify as magic realism, we see the old woman welcome the omens of her end and, at the moment of death, return to the ancestors who wait for her. You can guess what happens to Reta, Mollie's sole remaining sister.

Behind this horror, Hale plays the part of the perfect white ally, exuding paternalistic comforts as the self-anointed king of the Osage Hills.

Proving again that he's never better than when under Scorsese's direction, Robert De Niro lets the camera find the atrocity in the mastermind's actions while foregrounding the façades that keep him at the top of the Fairfax food chain. Watching the master's old muse share the screen with the new is a pleasure that defies description, with both actors articulating a vision of the banality of evil that's nearer to the ideas Arendt put forward in Eichmann in Jerusalem than anything in Glazer's The Zone of Interest. Through Ernest's systematic capitulations and complicities, the process through which wickedness is normalized appears written in blood across the screen.

The camera witnesses how each prejudice-supported reasoning cascades into further rationalizing evil, new transgressions setting the stage for future iniquity. One horrible action is justified, so the next increment of evil doesn't feel far off or too horrendous to consider. Let the sin pile on sin like snow before an avalanche, and you can do the most heinous things while still couching them within notions of acceptable behavior. When a whole society sanctions it, the breeding ground for corruption becomes so volatile anything seems possible.

As we grow to question Ernest's awareness of his own actions, the camera sees through it all.

At one point, Scorsese and DP Rodrigo Prieto grow so bold as to depict Hale's influence in terms of Biblical damnation. Regard the white devil as he looks upon his demons, those mindless lackeys busy doing their master's bidding. Fire and brimstone burn the air until it wavers like water, our vision boiling in this brief poem that cuts through any attempt at escaping guilt with a mighty strike. Many such moments abound in Killers of the Flower Moon, the movie pausing for minutes of plotless contemplation. Another example occurs much earlier, an inverse of Man's relationship to Nature. Instead of fiery exploitation, that scene beckons a respectful silence amidst thundering roars.

These are precious variations that Thelma Schoonmaker peppers throughout. Overall, Killers of the Flower Moon moves at breakneck speed through its complex history, but these peaceful interludes stop it from being unrelenting. That's not to say the film is concerned with being fun, differing from many of Scorsese's most popular titles in that vital aspect. Violence, when it happens, isn't spectacular either. Instead, it's dry and crude, ugly in a dull everyday manner whose casualness will send chills down your spine. The extended runtime further drains the possibility of easy entertainment, settling for a heaviness that starts at the gut and slowly makes its way up the throat. By the end, you can hardly breathe.

By the end, there's also no closure and certainly no catharsis. How could there be when so many cases remained uninvestigated, let alone solved, justice never served? How, when there's no end to the Osage's struggle beyond the Reign of Terror into our day and age? They persevere and thrive, but the scars of injustice will never heal in the ways a Hollywood ending would require. All that's left is that nauseating feeling chasing you out the theater. The film feels tired and beaten down, dragging you to grieve along with the victimized characters and their stalwart descendants, the screen a conduit for collective mourning in similar fashion to the axe burying from the prologue.

Some might regard this as a failure on Scorsese's part when, in fact, it is one of the film's greatest triumphs.

Its most important victory, however, is how Killers of the Flower Moon negotiates a study of white man's evil and Ernest's forfeited soul with a celebration of Native people. This manifests in the attention paid to accurately depicting the Osage culture of yesteryear, with production designer Jack Fisk, costume designer Jacqueline West doing some of their best work with the help of a veritable battalion of Indigenous artisans. Language-wise, it's commendable how parts of the film are made ineligible for all who don't speak Osage, the intermittent subtitles privileging an insider perspective rather than facilitating outsider spectatorship. And then, there are the formidable Native actors, from Cara Jade Myers' unmoored anger to Tatanka Means' sly deception.

But of course, nothing can compare to what Lily Gladstone accomplishes, delivering Scorsese's 21st-century answer to what Dreyer and Falconetti's Passion of Joan of Arc, and maybe even the director's own Scenes from a Marriage. Her face carries the weight of immense responsibility, personifying a people's sorrow while also delineating the specificities of Mollie's person, her attachments and contradictions, her pain, yes, but also her strength. It's no wonder that criticis worldwide have been besotted since Cannes, with many applauding the actress' ability to interpret her character's crescendo of bereavement into anger. Still, she's all the more impressive when illuminating ephemeral joys, the petty frustration of an unfavored daughter, the respite of one afternoon's erotic folly. With DiCaprio, Gladstone delivers movie magic, the kind that's only possible when stars collide and chemistry ensues. Together, they keep you at the edge of the seat as husband and wife second-guess what they know about the other and, in her case, the limits of trust.

Even if only for its depiction of Mollie Burkhart – including the acknowledgment of the form's limitations to do her justice - Killers of the Flower Moon deserves to be considered one of Martin Scorsese's foremost masterpieces.