Some actors thrive through mimesis, reaching for realism when performing. In cinema, they bring the actuality of everyday life to the screen, psychology and material terms. Or they replicate others like straight mirrors. Since midcentury developments, that approximation of off-screen life has been standardized into what most recognize as "good acting." It's the mainstream, the rule, the de facto way of doing things. But is it the only way? I would think not and have grown to appreciate those who step outside those lines, whether deliberately, through their director's influence, or by mere accident.

When done right, embracing fakery may feel more honest and insightful than the attempt to copy - realer than real, truer than truth. All this to say, I love Natalie Portman at her most artificial and absurd…

For years, Natalie Portman wasn't one's idea of a great actress. She started young with excellent reviews in Léon: The Professional but soon fell into a trap of perceived incompetence. Most folk don't regard her stint in the Star Wars universe as especially good, and even her solid turns in the likes of Where the Heart Is and Cold Mountain revealed her limitations as much as they proved that, in the right circumstances, she could act. Thus contextualized, Mike Nichols' Closer felt like a fluke, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to shine in an ideal for Portman's specificities.

It earned her a well-deserved Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination. Yet, at the same time, it didn't dispel a general consensus that she wasn't all that. Still, looking back, her best moments in that film feel like a signal of what's to come, an early indicator that Portman was best when transcending notions of conventional realism. A striptease conversation with Clive Owen persists in the memory, not because the pink-wigged pixie drips with authenticity. Instead, it's the performative nature of the scene that stands out, how Portman articulates a game of make-belief cloistered within another characterization.

An ordinary mirror no more, the actress reveled in the chance to clash reflections. In Black Swan, she got to shatter them for a director most interested in examining the jagged edges pinked with blood. The cracks are Aronofsky's focus, but they aren't what I most prize in the Oscar-winning performance. A mirror's effort to stay whole fascinates, as do instances when Portman's ballerina is acting, whether for herself or others, when she's subsuming her neurosis to play the on-stage swans. It's the theatrical gesture in dreams and the self-regard before a vanity, the perplexing brittleness of a final dive.

What a pity that her career post-victory seemed calibrated for stardom and commonplace prestige with a detour into Malickland for some unconvincing abstraction. By a miracle, this path took her to Pablo Larraín, and, at long last, the world got to see what Portman could do with the right vision. As if playing a theoretic deconstruction of biopic performance, she's mannered to the point of grotesque as the former First Lady, the gulf between thespian and role ever-present, stark and impossible to ignore. One is always aware of Natalie Portman within this Jackie, so much so that the friction becomes the point of the exercise rather than its failure. It's the opposite of disappearing into a role.

Mike Nichols made Portman a mirror looking into its reflection. Aronofsky studied the cracked surface. Larraín reconstructs the shatters as a polyhedric sculpture, every edge showing a different angle. In more painterly terms, it's a feat of cubist portraiture with all the possible perspectives coexisting on the same plane, flattened for screen projection but vivid nevertheless. Think about that glorious passage when the moment of assassination is invoked, tears spilled and voice trapped in reliving grief. But then she disconnects from that emotion and proclaims not to smoke while enjoying a cigarette. It's as startling as it is brilliant.

Jackie is performing for numerous audiences, and so is Portman, their artifices combined so that we get to examine History as a myth in construction, a collage necessarily diverged from lived experience. If you can't imagine this is how the real person behaved, that's fine, but it's also missing what the film offers, its games and wildness. Jump to 2018, you've got two other gems of unconvincing humanity in Annihilation and Vox Lux. Again, the brilliance lies in the exertion of actorly muscles, effort plain to see, whether extrapolating alienation from beyond or a pop star's reinvention of the self with a crazy accent to match.

Yes, maybe this is me rationalizing being enthralled by "bad acting," finding purpose in the mess that entertained me. But, some things shouldn't matter when examining art or, at the very least, should be flexibly considered. What matters isn't an adherence to set rules, ordinary dichotomies of good taste, or, to an extent, the artist's intention. What should matter is the final film, the unfolding untruth on screen, and how it provokes reactions of curiosity cum revulsion, how it inspires reflection and shocks new ideas into being. When tapping into artificiality, Natalie Portman is one of Hollywood's most fascinating stars.

Even she must be aware of it to some extent, having championed May December into existence as its producer and leading lady. It was Portman who supposedly brought the project to Todd Haynes, putting into motion this twisted take on the Mary Kay Letourneau scandal. She plays Elizabeth, a TV star aspiring to serious actressing, who goes to Georgia on a research trip for her next project. Twenty years after the fact, a movie is being made about the pet shop employee who started a sexual relationship with her tween underling. After jail, Gracie married Joe, with whom she had children, complicating a bond born out of what most would classify as abuse. Elizabeth will be Gracie on screen.

Within its kaleidoscope of excused predation and whatnot, May December forms a troubling portrait of its three central personalities. At times, it feels like each actor is playing within a separate movie - so, while Julianne Moore and Portman inhabit a campy perversion of the serious topic, Charles Melton punctures the audience's understanding by illuminating the story's human cost. It's the kind of movie that will coax you into uncomfortable laughter, make you feel at ease with the lark, and then pull the carpet from under you. May December acts like a cascade of contradictory impulses at odds with the character's desire for tidy explanations and a peaceful status quo.

The fundamental facts of this tabloid fodder reside in a gray area that its protagonists can't abide, nor can the society that created them or the industry ready to cannibalize into indie film Pablum. There's no easy way out of the conundrums proposed, and how the actors work like puzzle pieces that won't fit is part of the "fun." Portman and Moore, in particular, are playing two sides of the same coin, manipulative entities that weaponize white womanhood and apparent sexual fragility, their projected helplessness a crucial tool in their dealings with Melton's Joe. But, of course, for as many similarities, they aren't close. Elizabeth and Gracie are miles apart.

And that applies to how the actresses embody their roles. Moore plays Gracie like a real person, all lisping self-delusion under the microscope, finding a litany of details with which she gives access to Gracie's interiority while guarding parts of the woman from us, maybe even from the character herself. On the other hand, Portman is more conceptual, like a parody of Liv Ullmann's Elisabeth Vogler that's less eerie but more obviously vampiric. I know that, during certain scenes, I felt the urge to go all Cate Blanchett in Notes on a Scandal, screaming "you're a fucking vampire" at the screen. A fucking vampire and a mirror, of course.

Many scenes in May December are staged around such objects. And they do invoke a sense of Persona through the looking glass, tawdrily shot like an artsy soap opera, digital footage with post-production grain on top. Even the image quality is a wannabee deception in this imitation game!

That aesthetic falsity is reflected in the gap between Gracie and the Elizabeth-made facsimile that appears at the end of May December. That is the fulcrum of Portman's work. Her feeble-voiced Elizabeth copies gestures with studied, über self-conscious, poses, highlighting the superficiality of mimicry all along. Every interaction is a chance to add new assets to her repertoire, akin to ChatGPT accumulating data points for its AI creation. Only she's almost human, as much as a screen construct can be, while also representing a conflagration of ideas on the very notion of acting. It culminates in memorable scenes that might be the best examples one can get of Portman's weird brand of brilliance.

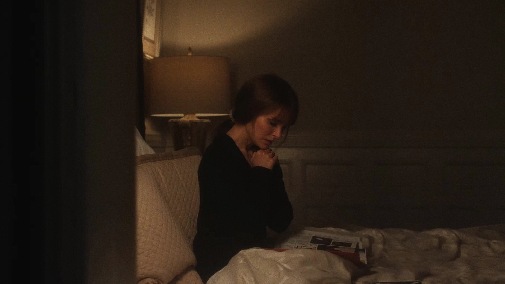

There's the final interaction with Joe when a piece of correspondence is paid for with the illusion of intimacy. The actress has never been as cruel as when she rebuffs Melton's lost soul, delivering the world's hollowest reassurance before stabbing him with "this is just what grownups do." Later, as she reads the letter to her mirror image, Haynes has Portman deliver the monologue like a performance whose construction's caught in media res. She spends a good part of it adjusting the angle of her mouth, twitching facial muscles in the way a malfunctioning android might. It's unnerving and hilarious, humanity inverted into a black hole – the void staring back.

As Elizabeth, Portman's the actor of all actors, a camera in the flesh and the funhouse mirror. In that role and beyond, she's the queen of artifice. All hail the queen!

May December is currently in theaters, enjoying a limited release before it drops on Netflix on December 1st.