Each weekend Nathaniel we'll be discussing a movie requested by you! SPOILERS ahead so if you haven't screened this on Netflix do that first.

The idea was to kill myself, not feed the damn fish.

Who is the most f***ed up character in Alfred Hitchcock's Marnie (1964)? The answer is not as simple as it appears. The titular ice queen blonde (Tippi Hedren) is sexually frigid, terrified of lightning, a compulsive liar, a serial thief, and disassociates almost instantly at the sight of the color red. She has so many issues she's a full series of crazy. But while Marnie is a loner she's hardly alone in her own film when it comes to needing serious amounts of therapy...

Where was Louise Latham's Best Supporting Actress nomination?

Where was Louise Latham's Best Supporting Actress nomination?

Mark Rutland, her boss / captor / husband (Sean Connery at peak Thunderball hotness), probably looked sane to moviegoers once upon a time (aka 1964) but he's not of sound character or mind either: impulsive, shifty, amoral, manipulative, sexist, enabling, also a liar... and rapey, too.

Then there's Marnie's ailing mother Bernice (an impressive turn from Louise Latham) a life-long liar and guilt-ridden former sex worker. To up the competitive ante of "troubled" on display, Bernice is also judgmental, avoidant, repulsed by her daughter's touch, and passive aggressive about any and all maternal expectations. Even her homemade pecan pie is weaponized to withhold love rather than give it. Even at film's end when the truth is finally out, and Bernice has declared that she does actually love her daughter she still can't give that love out, shooing away her daughter again.

Get up Marnie, you're aching my leg.

With all of these complete psychological messes vying for screen time Mark's sister-in-law Lil Mainwaring (Diane Baker) comes across as positively well adjusted. It's all relative of course. Her big (terrific) scene, for example, is like Red Flag Word Salad...

Lil: I have absolutely no scruples. I'd lie to the police or anything... I'm just offering you my services: Guerilla fighter, perjurer, intelligence agent.

Mark: You seem to be growing up Lil. I expect what we should do is find you some young man. What's your type?

Lil: I was waiting for you. I'm queer for liars.

Lil is trying to raise Mark's cool temperature with that last insult but Baker's performance is charismatic and skilled enough that you also know it's true.

To love Marnie (1964) as a whole, a divisive picture within Hitchcock's treasure-trove of a filmography, might actually depend on sharing Lil's kink. Are you queer for liars... and, thus, Marnie itself?

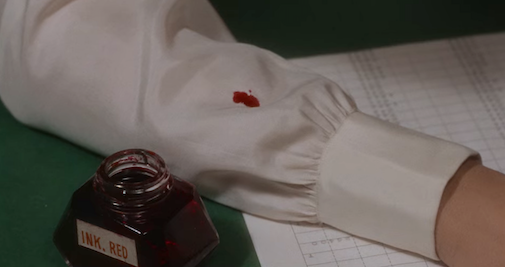

I personally struggle with this 1964 picture which was only a modest success upon release. Though it has collected ardent fans since, its qualities are easier to intellectually and aesthetically admire than to be emotionally invested in or excited by. Hitchcock's films always provide the former and his classics also provide the latter. Once again the filmmaking is top-notch. Was there ever a filmmaker better than Hitchcock at shooting places, items, accessories, costumes, and making them not just characters but fetish objects? The camera (cinematography by Robert Burks, in the last of his Hitchcock collaborations) consistently zeroes in on things like keys, vaults, bags, doors, guns, desks, money, written instructions, phones, and of course colors and costume elements. Many of them take on the weight of Chekhov's gun and you know they'll go off eventually which is half the fun.

Hitchcock's films sometimes get too plotty (Marnie definitely is) but he's a supreme visual storyteller. You can play "Best Shot" with any of his movies and have a ball. Here are my three personal bests from Marnie...

Bronze: This dreamlike shot of Marnie, disassociating as her new husband kisses her is visually thrilling -- how did they shoot this given the movement to the bed? -- but it's also too disturbing to be a "favourite" shot as its easy to interpret the moment as a rape scene.

Who's the dish?

Silver: The first third of Marnie is all set up and Lil is the last main character that we meet. Her introduction is simple enough on the surface but there are a lot of moving pieces given the plot and the interpersonal dynamics which are all forming in this one scene. This shot which "ends" her introduction is brilliant. By entering the office Marnie happens to be staring at (this is Marnie's POV) Lil becomes the temporary obstacle. She's blocking Marnie's view of the vault with all the delicious money in it and she's also talking to Mark Rutland (the boss) who we cannot see or hear in this shot. With the door splitting the frame, Mark and also Mark's motives and also Mark's feelings about the women in his life (both Lil & Marnie) are literally made opaque.

Cheekily, Lil closes the door on us and, thus, Marnie. It's as if she knows we're all staring.

Gold: You could -- and someone surely did -- write thousands of words about Marnie's most bravura sequence when our serial thief, thinking she's alone, makes her move on the Rutland vault. She doesn't know a cleaning lady has entered the office. Hitchcock doesn't quite give this scene the Rope treatment as there a few key edits but he holds this particular shot for an agonizingly fun length of time as we fear that our icy amoral "heroine" will be discovered and we also wonder when she will realize she's not alone. Just as exciting as the shot composition is the choice of the sound. This is the one key sequence where there is no score at all so it's about listening to the mop sloshing on the floor and wondering if Marnie will hear it... or be heard if she doesn't step carefully away from the scene of the crime.

Maybe lose those high heeled shoes, Marnie?

Speaking of shoes. All the close-up granted fetish objects -- like that vault which we see multiple times -- do come back around and pay off. But there's little that's truly thrilling about the resolutions (apart from the entirety of this scene which begins, continues, and ends perfectly). So when the film comes to a close, it just kind of ends, risking a flatness that rivals the matte paintings that frame Bernice's Baltimore street where Marnie was so traumatized as a child.

Decent women don't have need for any man. Look at you, Marnie. I told Miss Cotton. Look at my girl, Marnie. She's too smart to go getting herself mixed up with men. None of 'em!

Would it help if Marnie (and Marnie herself) were queerer? It's easy enough to "read" the protagonist's pathologized lack of interest in sex as coming from a place of either asexuality or sapphic tendencies than from childhood trauma. Still the film, not to mention Tippi Hedren's uneven star turn -- never really indulge a queer reading in the way some of Hitchcock's greater films (Rope, Strangers on a Train, Psycho for example) and more psychologically adventurous actors do. Though attempts at remaking Hitchcock films are usually giant wastes of creative energy, Marnie might just be the movie that someone should take another stab at.

Marnie's place in Hitchcock's canon is also troubled by sheer chronology. After four consecutive widely beloved films that are often considered masterworks (Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho, and The Birds) -- a prolific hot streak that has only rarely if ever been equalled by another auteur -- Marnie, can't help but pale in comparison. Hitchcock only made four more movies after this. They're not entirely without magic (especially 1972's Frenzy) but, as with the best moments of Marnie they're just that... moments. The masters last five films have flashes of hot red genius that widen your eyes and quicken your pulse. But like Marnie you come to your senses too quickly, never fully transported but only temporarily jolted alive.

Previously: Babette's Feast (1987) and Dick (1999)

Next weekend: Fatal Attraction (1987)