Born Maximillian Oppenheimer in 1902's Germany, Max Ophüls chose the pseudonym to avoid embarrassing his father as he pursued an acting career in theater. He'd change paths along the way, finding purpose in directing actors rather than reveling among them. Moreover, the paternal humiliation was never to be beyond the scandalous nature of theater since the man who would one day make tracking shots his calling card was a virtuoso. As the roaring twenties gave in to a new decade, Ophüls' ability would help him transition from the stage to the screen, where he began as a dialogue director at UFA.

But of course, being Jewish under the Nazi regime was deadly, so the director fled from Germany to France, stopping by Switzerland and Italy...

When France fell, Ophüls fled again, finding refuge in Portugal before leaving for the US. There, championed by writer-director Preston Sturges, the polyglot cineaste found work, though his position in the industry always felt ephemeral. Ophüls' late-40s work thus represents something of a Hollywood limbo, untethered from the rest. Compare to the French films he made after returning in 1950, before his premature death in 1957. Those are usually regarded as the peak of his artistry.

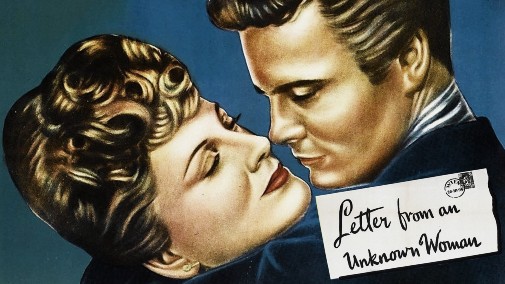

I tend to agree with such notions. Still, if asked to name my favorite Max Ophüls film, I must point to one of his American efforts. Although to be fair, it's the most European of the lot, a sort of midpoint in the auteur's evolution - Letter from an Unknown Woman, which premiered in New York exactly 75 years ago.

Adapted from a Stefan Zweig novella, the film finds its setting in the impossible elegance of turn-of-the-century Vienna, beautifully recreated by art director Alexander Golitzen and costume designer Travis Banton. Not that you will find much splendor in Letter from an Unknown Woman's introductory passages. It starts on a rainy night, ink shadows embracing three men in a carriage. They're well dressed, white ties and top hats the lot, but while their tone is jovial, the conversation feels fatalistic. Something is bound to happen come morning. Something that might bring the end of Louis Jourdan's caddish, ever so handsome pianist, Stefan Brand.

As he ascends the stairs to his apartment, raindrops glisten like silver glitter over his cape, and the camera follows. The movement is akin to that of a feline stalker, stalking across the well-appointed hallways, keen attention married to cold disinterest. Coffee and cognac shall be the man's companions tonight, his lonely servant packing luggage for a hurried escape. Whatever awaits Stefan at dawn, he doesn't plan on being there to take responsibility. Despite the ticking-clock nature of the scenario, these scenes unfurl in a state of near-hypnosis. We're cradled by the roving frame, rain pattering, strings weeping faintly, on the soundtrack.

Music shall be the conduit of much despair in Letter from an Unknown Woman, starting now, when the sudden jolt of sound brings our attention to the piece of paper in Stefan's hands. It's a missive from St. Catherine's Hospital, curling letters spelling out, "By the time you read this letter, I may be dead." No wonder the score stops on its tracks, and so does the camera still itself. It takes a deep breath, swallowed dry. Another disruption is that confidence, so effortlessly projected by Jourdan – it's gone. The musician and his audience are set for a night of confession and remembrance. As one pours over the text, Joan Fontaine's voice narrates the tale of poor Lisa.

Pushing in and out of focus, dissolving into the past, the film brings us to the memory of a girl's second birthday. Everyone has two: the day of their physical birth and the beginning of their conscious life. In Lisa's case, the latter happened in the Spring of her teenage years, one day when a horse-pulled van stopped in front of her building, beautiful things coming from its insides - harps, a piano, detailed landscapes to decorate the walls and gilded volumes to furnish bookcases. Fontaine's eyes spark with youthful curiosity, a pretense of childhood that convinces despite its overt artifice. With enough sincerity, a lie will sound like truth. And, after all, illusion is often kinder than reality.

Don't you want to get lost in it? Moreover, if any character deserves some kindness, it's Lisa Berndle, her soul sacrificed to love and passion, falling for those sophisticated objects and then for the music that scores her everyday life, echoing from the apartment above. The first time Stefan crosses paths with the youth, a pane of glass separates them, the window a materialization of the immovable barrier between the two. And yet, no crystal distortion could ever disguise the contrast in gaze. To Stefan, she's nothing. To Lisa, he's the world's greatest wonder.

Though we experience these days gone by through her writing, Ophüls' camera is wiser than his protagonist, repudiating the idea of merely replicating her subjectivity. The frame will always consider Stefan's nature while allowing Lisa's lovesick delusions to exist without contradiction. Part of it is the flush of melodrama so gorgeously realized by the craftspeople behind the camera. But a great deal of the magic comes from Fontaine. She articulates these differences between the character and the audience's perception across the evolving portrait of a girl growing into womanhood.

In the letter, three meetings shall be detailed, with Lisa becoming more elegant each passing year, convinced she can mold herself into someone Stefan might treasure. Her obsession, as expected, remains invariable. It could be cruel if not for Ophül's gentility or how the silver screen radiates affection when framing the star. And so, time flows, unrequited love remaining that way as if some cosmic rule of the universe. With its period specificities and focus on everyday routines, Letter from an Unknown Woman is small in scope, but its passion suggests something bigger than life, bigger than man.

It's divine ambrosia that kills the mortals foolish enough to drink it. But in Lisa's case, we sense she might disappear from this plane if she doesn't take it to her lips. So great is her love that a soul and its yearning become synonyms. What is she if not the devotion dedicated to a man for whom she's a slippery non-entity, infinitely forgettable? To stop would be to disappear into nothingness. Then again, Lisa seems content in living limbo-like, forever on the threshold of her happiness, existence frozen in the form of a winter wonderland. According to her, during the most aching romantic outing in film history, a snow-covered park is more beautiful than one blooming with flowers.

The roses of one's imagination will always be better than the true spring blossom. Even when maturity sets in, and we rediscover Lisa as a married woman with a child, that idea persists in every measured movement, each gesture. Fontaine's voice indicates the sophistication of one who learned to curate herself into the perfect society wife. She's learned contentment but doesn't believe in it. Pay attention, and you'll perceive how hollow this joy is compared to that stolen evening with Stefan in the snow. A glimpse at the opera shatters the facade, for Lisa never stopped drinking her poison.

Such masochism, such madness! It could frustrate or drive the viewer mad, but it doesn't. Instead, it hurts, sentimentality and formal precision hewed to the shape of an icepick which the film attacks, plunging it into our hearts. Through it all, the unknown woman remains fascinating, as if daring us to know her agonizing depths. Indeed, when considering the martyrdom of Lisa as portrayed by Fontaine and Ophüls, it's easy to understand why it has fascinated great writers of film theory and criticism with a focus on femininity and feminism - Gaylyn Studlar, Tania Modleski, Molly Haskell, Angelica Jade Bastién, to name a few.

I can't claim to be able to explore Letter from an Unknown Woman with equal intelligence or wit, their insight. However, I couldn't let the opportunity pass by to wax rhapsodic about this one of my favorite films. Caught between a swoon and the surrender to tragedy, the work is the ultimate testament to Max Ophüls's style and unique talents, his formalist proclivities contained by the restrictions of American studio filmmaking, and the public's demand for good old weepie. Regarding Joan Fontaine, she was never better than here, delivering the performance that, in a just world, would have been the one to earn her the Academy Award. Oh, Letter from an Unknown Woman, how I love thee.

Letter from an Unknown Woman is currently streaming on the Roku Channel and FlixFling.