At the 42nd Academy Awards, the Best Original Screenplay category was a rarity of historical importance. You wouldn't know it in 1969, but all nominees would be studied for years to come. Whether seen as seminal works in their author's careers or cultural milestones with much to reveal about the society that produced them, the films form an illustrious bunch, going from Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice's pop psychology to the revisionist brutality of The Wild Bunch. The winner was Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, a western which has inspired queer readings for over half a century though it was far from the queerest picture in the race.

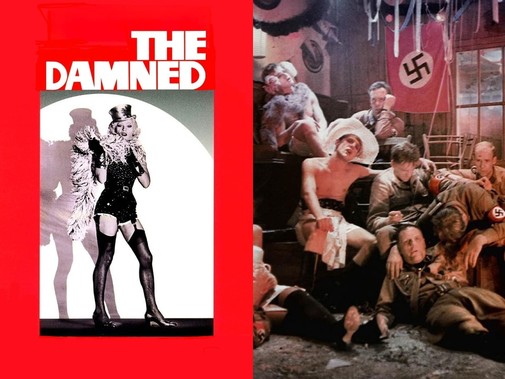

That would be Luchino Visconti's The Damned, marking the start of his German trilogy, the international metamorphosis of his cinema, and the most open expression of gay sensibilities in his oeuvre to that point…

From Senso to The Innocent, Luchino Visconti treated his aristocratic characters as a collector might handle prized butterflies. They're skewered still and flattened down by a plane of glass, the better to appreciate painted-like wings. Oh, but there are limits to the metaphor, the director prone to do more than just jab a pin through the humans in his scripts. Instead of a needle puncture, he often preferred the scalpel slash, his films dissections. From the opposite direction, there's empathy despite the vivisection, the contradictory compassion of a man who was all contradiction.

Born Luchino Visconti di Modrone, Count of Lonate Pozzolo, The Damned's writer-director was that obversion of a communist nobleman. Going further into the wonderland of incongruity, Visconti considered himself a Catholic until his dying day despite being openly queer. As an artist, he was one of the sires of Italian Neorealism, yet his most famous works renounce documentary-like depictions to strive for operatic grandeur, melodrama another of his passions. These conundrums extend to the man's identity as a European, national affinity, and cultural fixation out of sorts.

Like many a Mediterranean princeling wanting to affect above his Latin origin, perchance a Marxist yearning for proximity to the philosopher's motherland, Visconti prized his family's Germanic ancestry. He loved German culture and its Austrian sister, Goethe, Mahler, Wagner, the nostalgia of Zweig and Thomas Mann for a dying empire. Attraction led to fascination as that nation, rechristened Weimar, seized itself into ruthlessness with the rise of the Nazi party. Visconti went there in the aftermath of the 1933 political frissons but, unlike his ancestry, the director rarely referred to this trip. Still, it left a mark, firebrand.

Maybe he saw Germany as fellow paradox. Think of the love for purity, youth, power, the past's exultation, beauty made politics, the nominal banner of socialism, handsome virility elevated to a society's essential value. Yes, it's terribly easy to imagine Visconti recognizing parts of himself in Hitler's empire. But, as ever, there's contradiction, for violence was anathema to his conceptions of justice. The regime's extermination efforts of culture and peoples, its hatred of difference unforgivable. For the likes of Visconti and his beloved Mann, Nazism was the best of Germany inverted into its worst.

On a queerer note, the 30s were also when Visconti's relationship with German-American photographer Horst P. Horst prompted the Italian to accept his sexuality, an identity targeted by the Nazis. Experiences sutured together like some hideous Frankenstein monster, Visconti's Germanic obsessions always enlivened his queer sensibilities. And so, it would be with his German trilogy, though it didn't begin by being German at all. Macbeth was the starting point, the British Profumo affair as a real-life basis of adaptation. The endpoint is Hamlet, tempered by the Krupp family history.

The Krupp patriarch was an industrialist who Hitler relied on to finance the war effort, architect of such systems as the appropriation of prisoners to forced labor, turning the regime's victims into its engine. In The Damned, Dirk Bogarde plays Friedrich Bruckmann as an in-film representative of Alfred Krupp, a 20th-century Macbeth with his own Lady in the form of Ingrid Thulin's Baroness Sophie Von Essenbeck – industrialism and aristocracy as lovers, a demonic union in service of the greater evil. But, of course, If Friedrich and Sophie are the Macbeths, her son, Martin, is Hamlet. He would be played by Visconti's then-lover, Helmut Berger.

As the auteur's interest shifted from the couple to the young man, so did The Damned metamorphize into something closer to Shakespeare's Danish tale. If one wants to continue this literary path, Visconti's narrative has affinities to the Bard's historical cycles, parallel lines of family strife and History traced. This is something that those close to Visconti recognized as one of the man's putative faults when considering Germany. His vision was that of an outsider, romanticizing reality out of shape, making it myth. Such were Horst's objections to this folly. Indeed, he refused to watch The Damned.

It's no surprise, then, that the 1969 epic could be described as the most operatic of Visconti's films, perhaps even more operatic than the operas he directed on stage. That's why the English title The Damned is such a vexation, the original Wagnerian name Götterdämmerung preferred. This is the twilight of the gods, the earth's end, a chthonian apocalypse dressed in Nazi uniform. Fittingly, it starts in hellfire, the Essenbeck's steelwork empire a blazing industry, echoing those future fires that will soon incinerate books and human bodies.

There's another fire to consider in the text, one that codifies the first of The Damned's four acts. This primary movement in the quartet is the Reichstag's burning, our story starting on February 27th, 1933, when the Nazis' attack on the Parliament building colored the Berlin sky fire glow. It kick-started a propaganda machine that justified the culling of the party's enemies, both within and without. For the Essenbecks, however, it's background noise to an evening of celebration, the pater familias' birthday party when all the clan gathers 'round its scion, Baron Joachim, who'll be dead before the sun rises.

The news from Berlin arrives in the middle of a variety show for the still-living patriarch, intrigue having polluted the air with musty conspiracy. Children read poetry, and a chaste youth plays the cello, nothing too shocking. Certainly not enough to dispel the soap opera clouding the spectator's mind. It's the perfect time for Visconti to cut through all with a shot of queerness: Martin honors his grandfather by dressing in Marlene Dietrich drag and singing like the Blue Angel, the Essenbeck theater transformed to cabaret. Henceforth, family will be synecdoche for History, succession struggles in reflection of Germany.

In tandem, desire shall complicate every possible reading of the material. Not that one should presume a direct equation between depravity and decay, queer sexuality and evil like many critics have done since 1969. Take Martin, for example. His drag performance announces the dawn of queer sensibility in The Damned's twilight world, he's perceived with dangerous lust by the camera and even the narrative's guiding hand. However, beyond his first scene, every sexual foray tends toward the heterosexual. Not only that, Visconti places him as a male aggressor perpetuating venal violence against women and girls.

While Friedrich and Sophie act on their plan to shoot Joachim, the night's waning hours find Martin molesting the little Thalmann sisters, whose father shall be framed for the Baron's murder. It's a traumatic twinning like the birthday party and the Reichstag fire, the lovers plotting to take control of the steelworks while unknowingly leading Martin down a path of opportunistic radicalization. Furthermore, while Martin's hunger grows voracious and malignant – he rapes a Jewish girl who later kills herself - so does Nazi power grow in size like a cancerous mass spreading to every recess of the German organism.

He'll be soon assimilated into the sickness, but that twist won't be a sign of hedonism taking over. The opposite happens since, as destructive as desire might be, it's not inherently wrong. Certainly not comparable to Nazism. The regime in full bloom isn't sexual or desirous, seduction a trap, and nothing more. Its lure, typified by the SS costume, makes the men wearing it beautiful, beacons of erotic magnetism whose wantonness has been redirected to violence. Queer culture's fetishistic relationship with Nazi imagery has long been analyzed but seldom has a director elevated the cult of beauty to the realm of cosmic force cum damnation as Visconti does here.

Returning to the narrative, for Martin to become the perfect SS princeling, he shall be both beautiful and divested of desire, the inversion of his first scene. Sex, to him, is weapon only. One can even perceive his final punishment of Sophie – raping her into suicide like the Jewish girl - as his way of exterminating whatever queerness might have resided within him. She's the one who bedecked him in Dietrich garb, and the SS shall destroy the woman who dares feminize the masculine. Destruction through fucking, Martin's initial inklings of gender rebellion sacrificed at the altar of macho tyranny, his Oedipal complex curdled into hatred.

"You've subjugated me with your wigs and your lipsticks " – a piece of camp dialogue for the ages and the final station of Martin's arc, so horrible and extravagant, barbed madness teetering at the edge of absurdity as all good melodrama should. It's queer opera, alright! Ah, but this glorious mess still has so much more juiciness, and I want to sink my teeth into it. Before the end of this long essay, two scenes must be considered still. They are the peak of The Damned's queer provocation: gay orgy as heaven and straight marriage hell, the Night of the Long Knives sequence and the matrimonial climax of Sophie and Friederich, third and fourth acts respectively.

Though it's the film's most dialogue-less passage, the Night of the Long Knives was the first thing to be shot and fully scripted, Visconti's priority. In it, the SA "brownshirt" troops are depicted as enjoying a queer bacchanal before their bloody end, complete with cross-dressing galore. Within The Damned, the orgy comes closest to being a dream rather than outright nightmare, defying the aesthetic parameters the film constructed earlier. It also defies cinematic ideas of Nazi sex, including those depictions in The Damned's copycat children – Salon Kitty, The Night Porter, Lili Marleen.

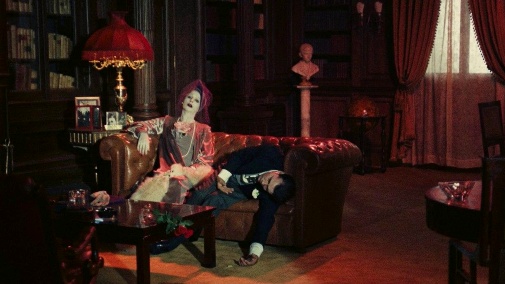

Part of it is that the male bodies are presented in a crescendo of disrobing, putting aside their stormtrooper trappings to achieve a purer state, a German body before its notions of purity curdled into hate for all that was divergent. Nakedness in the languidness of passion is then gunned down by uniformed masculinity, the fetishistic attire a death omen. In a poem of monsters butchering monsters, Visconti's spell of queerness has invoked strange grace. In contrast, the Essenbeck-Bruckmann wedding is graceless down to the bone though its content is much less outwardly depraved than what came before.

Heterosexual marriage is no happy ending but Nazi ceremony, diabolical rite. Powdered a ghostly pallor, near phosphorescent when cloistered within her dark palace, mother Essenbeck is no longer one with the living. She's gone beyond, Hamlet's matriarch like her first husband, a haunting upon this Teutonic Elsinore. Visconti has said that The Damned ends where Nazism begins, an erotic flirtation where the uttermost hetero tradition is the sign of a world left numb to sex of any kind – another atrocity for the count. How bizarre that this queer pandemonium would earn Visconti his only Oscar nomination, be his only film to turn a profit. Maybe the public and the Academy were more adventurous then. Perhaps they were madder. I think they were inspired.

The Damned isn't currently streaming anywhere. However, Criterion has a fantastic edition of the film, beautifully restored and as besotting as ever. Occasionally, it pops up on the Criterion Channel, so be on the lookout for Visconti's polarizing masterpiece.