As nominees, presenters, and other attendees arrived on the red carpet for the 63rd Academy Awards, they were met with righteous commotion. ACT-UP members picketed the ceremony, holding banners decrying universal inaction when over 102,000 people had already died by the modern plague of AIDS. During the festivities proper, activist David Lacaillade, who had found his way to the audience, stood up and shouted invective against the proceedings, demanding action and calling those who do nothing hypocrites. AIDS Action Now! Sadly, there seemed to be very little in the way of open solidarity inside the Shrine Auditorium.

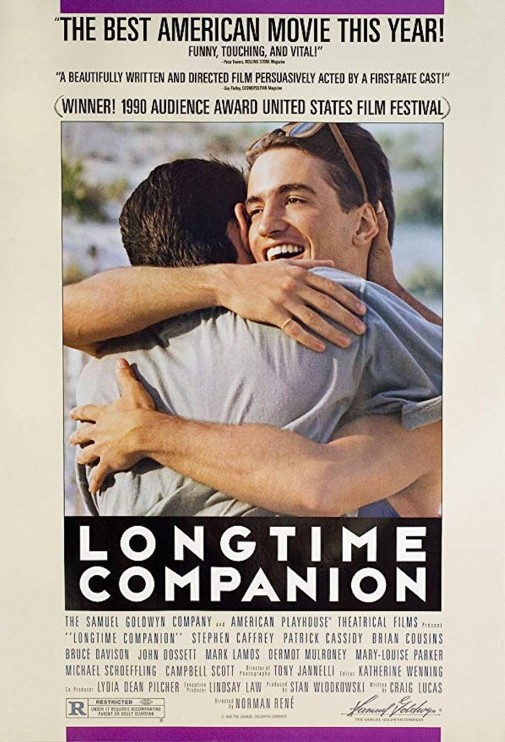

Earlier, protestors offered button pins emblazoned with "SILENCE = DEATH" to the folk walking the red carpet. Most people declined to wear them, but Bruce Davison was one of the few to don the message. He was also the rare example to wear it all ceremony – some people took them down before the opening monologue was through. Davison was present as the sole nominee from Longtime Companion, the first mainstream feature to depict the effects of AIDS in the gay community. Walking into the Oscars, he felt a heavy responsibility pressing down on his shoulders. In his own words, the actor was "carrying the torch for the people represented in this film"...

Early in the ceremony, when Brenda Fricker came on stage to present the fourth category – Best Supporting Actor – the torch-carrier would lose the prize to Joe Pesci in Goodfellas. Still, his achievement is worth remembering, and Longtime Companion worth celebrating.

Directed by Norman René from Craig Lucas' original screenplay, the film details a little bit less than a decade in the interconnected lives of gay men living between New York and Fire Island at the onset of the AIDS epidemic. Openly queer, Lucas drew inspiration from his lived experiences when writing the script, looking back to the trauma of his then-partner succumbing to the virus in the crisis' early years. A sense of authenticity underpins every scene in Longtime Companion, from its purview of libertine abandonment before gay Armageddon to its depictions of a community trying to rationalize an invisible threat, mortal and infectious, ruthless.

In intention and execution, it's a piece of humanistic portraiture, aiming for a collective sense of character rather than some Pablum hero's arc. René and Lucas aren't so much examining individual tragedies as tracing the convulsions of a community attacked by vicious pathology, by a society that'd rather witness their deaths than do anything to prevent them. Its very title reveals a mighty purpose, uncovering those rich existences brushed under the rug by conservative media. Back in the day, The New York Times wouldn't directly recognize a gay man's partner in their obituaries, choosing to offer the euphemism of longtime companion instead.

That's not to say the picture's perfect or inoculated against negative assertion. Representation-wise, while the white gay community is given its moment in the sun, every other racial and gender denomination under the queer umbrella is left in the shadow. If one were to judge the New York 80s queer scene just by watching Longtime Companion, they'd be justified in thinking it was almost exclusively white with no trans people around. But then, one must consider the specificity of POV, taken from the filmmakers' direct memories instead of a broader investigation outside their bubble. Would it feel as authentic if it stretched beyond those personal parameters? Maybe not. Maybe it'd be a whole different movie.

Then there's a more recent preoccupation with identity-based casting which paints new issues over old canvases. I'm referring to the contemporary effort to have marginalized people play themselves for the camera rather than having their stories told by outsiders. After all, a considerable portion of Longtime Companion's main cast identifies as straight, including Academy Award-nominee Bruce Davison. Pointing this out doesn't invalidate his incredible work. Indeed, I wouldn't trade his take on Longtime Companion's David for all the world's riches. It's too staggering to begrudge, beautifully articulated, played according to a tenet of empathy.

So, let's celebrate Davison's performance and the film from which it came. To follow Lucas' nifty structure, the character's journey is divided between the narrative's episodic stops, one day for each year, snapshots both brimming with generosity and a surprising lack of mercy. It all starts on that day when twenty pages deep, The New York Times reported on "A Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals."

July 3, 1981

Longtime Companion begins in summery ebullience. On a beach at dawn, a jogger runs alongside the foam outline of crashing waves. The sun is ideally placed to paint ocean and sky in the same shade of pink-tinged cyan, a postcard of 80s Fire Island in living color. No sooner have the titles started unraveling, Campbell Scott drops trow and jumps into the sea, a shapely ass welcoming us to the world of the movie. Though there's no evidence of this, I like to think this was the actor's way of showing his father the middle finger. During his 70s heyday, George C. Scott wasn't shy about sharing his homophobic views.

But we're not here to talk about Scott Sr.'s bigotry or Jr.'s performance as personal trainer Willy. In the cross-cutting montage of city slickers and vacationers, René introduces his cast of characters, including Bruce Davison as an affluent middle-aged gay man having a gaggle of gay friends over at his and his partner's beach house. David and Sean are hosts to Willy and John, the older men exuding the blue-blooded airs only the filthy rich can master. The contrasts don't end there since, unlike the others, David seems to take the NYT news story with an added note of seriousness. Even in his case, however, it's easy to brush aside dark omens to enjoy the hot sun.

Lounging on the beach, a glass of white wine in hand and opera playing on a handy boom box – has anyone looked gayer? Later, during a bustling tea dance, we see Davison playing the part of the wiser gentlemen trying to keep up with the younger crowd, the responsible adult amid partygoers. He still tries to convince himself he's having a good time, but maybe the pretense can concede to reality. Some drinks in, making sounds is on the table, inhibitions abandoned for the ecstasy of sharing joy with friends, making them laugh a merry riot. It's a sunny Elysium before the descent into hell, a last glimpse of smiles before sorrow, a community before disaster hits.

April 30, 1982

John is sick, taken to the hospital with pneumonia, and only David and Willy are there to visit. Davison exudes patrician airs sitting in the hospital waiting room, but the scene is not about class dichotomies, intrusions and whatnot. Instead, one feels the contradicting tensions of a comforting friend whose words say one thing and nervous hands another. As the details of John's condition become clearer, the sibilant hiss of panic starts to cram its way into line readings, squeezed tight through a performance of projected confidence. Those wavering notes of composure make a savvy picture of stalwartness in the face of crisis. But of course, this is just the beginning.

June 17, 1983

A return to Fire Island recalls the carefree notions of the first chapter. Only that tone now feels gossamer-thin, fragile on the verge of collapse. Playing host, David personifies the subtle unease, hollow smiles galore as moralistic talk infects the holiday chatter. As before, he'll occasionally capitulate to actual glee, like when celebrating Sean's success as a soap opera scriptwriter. Sadly, the bloom of delight is short-lived, wilting before the next sunrise. At night, an argument breaks between the lovers, Sean suspecting he might have 'it.' The scene's a beautiful piece of acting, a pas de deux where one dancer keeps evading Lady Truth who's prancing across the hall. Their crash is inevitable.

September 7, 1984

Sean is sick and confined to a hospital bed. Still, things could be much worse, and a temporary recovery seems on the horizon. Congregated around the patient, David and other friends give in to gallows humor. Davison looks natural with that mask of unwavering support, automatic smiles at the ready, and a veil of solidity draped over one's soul. It's the façade of a supportive loved one who's helpless to stop the incoming horror. Carve a hole in the wall he erected, bigger than glory so the whole body can pass through. On the other side, you'll see a desperate man, hands turned claws, nails breaking bloody as he tries to keep a hold of fledging normalcy.

March 22, 1985

Hospital rooms abandoned, the ailing Sean has deteriorated to dementia, David turned writing partner as he tries to control the uncontrollable. Talking about his lover's potential blindness, it's astonishing how Davison keeps calm, direct. The man who once could barely conceal his nerves in the waiting room has grown carapace so much stronger than that other crumbling wall. It's a hard-won development, only achieved over months of constant struggle to keep afloat. When, during a stroll in the park, a confused Sean urinates in public, Davison surprises once more with how he plays the incident with little in the ways of melodrama.

There's no need to be demonstrative or call attention to the pain felt by those who witness their love's demise on the sidelines. Thus, pragmatism crowns David's head, not quite beatific. Filmmakers and their cast feel more interested in portraying humans than anointing saints.

January 4, 1986

Catatonic, Sean has one foot in the grave already. As for David, he's now sharing caretaker duties with an at-home nurse. The business of cleaning his lover's diapers is performed with dry, no-nonsense efficiency, potboiler shock pushed aside as the daily ritual is repeated for the camera with no particular fanfare. There's something different here, as the viewer soon finds out. After long-suffering years keeping his lover alive, David is ready to let go, to permit Sean the end of his torture. "It's Ok. You can go" is a line reading for the ages, starting casual but breaking barely, a strangled vowel at the end. Just for that, Davison deserved his nomination.

In fact, this is the clip the Academy chose to play during the Best Supporting presentation. Not that it's especially loud in that fashion so usual for awards clippings. You'd expect Davison to savor the moment, making it a showcase for emotional pyrotechnics, but he sacrifices self-indulgence in service to his character. Disciplined, it feels searing honest, restraint pulling the viewer forward to the blade held, straight out erect, by the film. Come into the metal and bleed, hurt, pierce yourself silly, self-evisceration as one's ticket to communal catharsis. After that ordeal, the newspaper term longtime companion feels even crueler, a barbed euphemism, so little signifying so much left unsaid.

May 16, 1987

David died, the world lives on. It's a testament to Davison's portrayal that Willy's eulogy makes perfect sense with our conception of a man we only got to know for a short hour, a swift six years.

September 10, 1988

Still no David. He only lives in his friend's memories, a reminder that you are what you give away.

July 19, 1989

Davison's absence is still felt, his David a creation likely to follow the viewer after the credits roll. We see him in a beachside epilogue, when all the ghosts party with the living, reunited in a Fire Island paradise of the imagination. We say farewell, dreaming of a world where the epidemic never happened.

Pardon the addition of some dates, but I think they are essential. The list is, by no means, expansive or wholly comprehensive. Still, it should get the idea across.

May 20, 1989

Actor Pete Evans was Craig Lucas' old friend, the two sharing many experiences dramatized in Longtime Companion. Afflicted by AIDS, he was supposed to play Sean but was too fragile when filming started. He was 38.

October 14, 1989

Michael Carmine played the small role of Alberto, with whom he shared the damned disease. He died at 30, never seeing Longtime Companion with a live audience.

December 3, 1990

During the Fire Island shoot, hair designer Joe Dal Corso recognized a house he used to share with half a dozen other friends. They were no longer living, and Dal Corso carried the same AIDS-related prognosis. Friends would be rejoined a little over a year after Longtime Companion's world premiere at the 1989 Mill Valley Film Festival. He was 41.

March 4, 1992

It's been rumored Néstor Almendros was meant to be the cinematographer of Longtime Companion but couldn't commit to the project due to AIDS-related complications. I couldn't confirm this through primary sources. However, it's notable that one of the Spanish cinematographer's friends and mentees, Anthony C. Jannelli, took on the responsibility, making it his feature debut as director of photography. Almendros' situation worsened still, and he died at age 61.

May 24, 1996

Director Norman René discovered he was HIV-positive between pre-production and the start of filming on Longtime Companion. He was 45, an oft-ignored figure of New Queer Cinema who brought gay lives to the mainstream, their fight, plight, joy, and resilience enshrined in Hollywood history.

Longtime Companion isn't streaming anywhere at the moment. However, finding a full version of the film uploaded on video-sharing sites is easy. Here it is on Youtube!

More 'Queering the Oscar'