Vast wild landscapes dominated the latter half of my second day at TIFF. First came Nikolaj Arcel’s The Promised Land, fresh off its Venice premiere and inflated by high expectations. Then, it was time for Snow Leopard, the last completed film of Pema Tseden, the remarkable Tibetan director who dedicated himself to expressing his country’s specificities on the big screen. He died in May at 53, leaving behind a body of work that felt like it was just entering its golden age with titles like Jinpa and Balloon. And so, an air of mournfulness enveloped the screening of his leopard-loving film, a poem of snowy peaks and the beasts that share them...

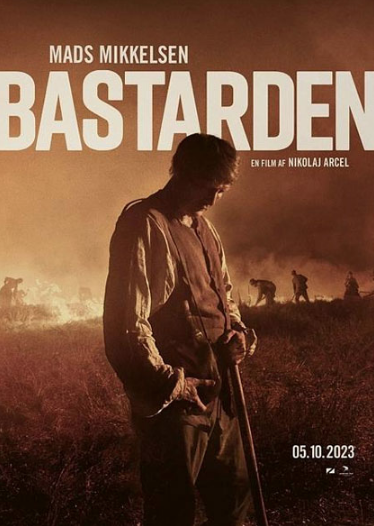

THE PROMISED LAND, Nikolaj Arcel

Mads Mikkelsen stars as Ludvig Kahlen, a destitute soldier of German origin who, in the mid-18th century, ventured into the Jutland heath, bent on cultivating the wilderness that had, so far, defeated every attempt to tame it. The vistas Arcel and DP Rasmus Videbaek capture are among the year’s most indelible images, evoking the feel of some classic Western displaced by around a century and an ocean, a sense of violence permeating every inch of \barren beauty. It’s certainly a step up from the director’s last Mikkelsen-starring period piece, A Royal Affair, that, for all it could boast about, couldn’t count great visual storytelling among its merits.

Still, the ghost of that film persists in distracting ways. Though inspired by a true story, The Promised Land takes its cues from Ida Jessen’s novel "The Captain and Ann Barbara," a romanticizing of history that bends it out of shape and into some unfortunate clichés. The screenplay by Arcel and Anders Thomas Jensen doesn’t do much to help matters, culminating in a villainous aristocrat like A Royal Affair’s King Christian 2.0. Simon Bennebjerg doesn’t necessarily help, though it’s possible to see why some would call him the picture’s MVP. In contrast to Mikkelsen’s stone-faced stoicism, the villainous turn has its charms, careening into anachronism and flamboyant sadism with no care in the world.

Overall, the film is impressive, verging on epic, but rather stolid in its conclusions. While classicism of this sort is to be celebrated, one risks the fate of being too old-fashioned for a project’s own good, curtailing a promising premise with unneeded tropes, cheap sentiment in communion with barbarism framed to shock rather than to provoke. I can’t say it’s a failure by any means, but it left me relatively cold after the praise it got at Mostra, including from The Film Experience’s own Elisa Giudici. Still, the flick is well-positioned to score for Denmark at the 96th Academy Awards. Right now, it’s among three finalists, with the submission revealed on September 26th.

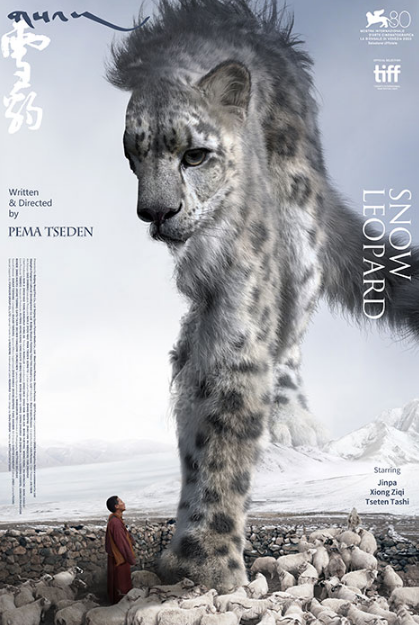

SNOW LEOPARD, Pema Tseden

From the unforgiving green expanse of Jutland to an even harsher environment, we go now to the Tibetan mountains, where deserts of rocks glisten with pearl snow and diamond ice, lakes freeze like mirrors under the sun’s golden glare, and beautiful creatures cohabitate with their human neighbors. At least, that’s the best-case scenario. In this particular story, the peace between species has been broken after a snow leopard jumped into a sheep pen and slaughtered nine treasured rams. We arrive at the scene through a local television team called to report the case, led by the beleaguered farmer’s younger brother, a holy man nicknamed the snow leopard monk.

In Beckettian fashion, the story revolves in circles with no resolution in sight, the ram’s owner refusing to let the predator go even if, as a protected endangered species, that’s against the law. It further oscillates between tones and registers with the assured abandon of a master filmmaking trying out new tricks and perfecting old ones. The use of long takes in the central portion of the narrative, for instance, evokes real-time realism while still offering perfectly composed frames, a quasi-Spielbergian technique with an art film twist. Passages more focused on the reporters are full of comedy to add to the farmer’s anxiety, phone calls from a distant girlfriend always on the reporter’s mind.

Still, the picture’s most exciting material happens in the threshold between the monk and the leopard’s POV, unfurling a strange bond that crosses into mysticism, man’s magnetic pull to a more natural and purer cosmos. In these scenes, realism goes out of the way along with its photographic precepts, replaced by high-contrast monochrome courtesy of DP Matthias Delvaux. It looks oneiric, sublimated into a not-so-unforgiving paradise where CGI animals roam through what look like living paintings of stone shadow against the brightest moonlight. It threatens kitsch without ever crossing the line, staying within the bounds of visual splendor so acute you can’t help but stare in awe at the screen.

Though it doesn’t reach some of the director’s previous peaks, Snow Leopard sings a beautiful swan song if Tseden’s unfinished last feature – started after this one completed post - never sees the light of day. It’s a sad state of affairs, but so is life, in and out of the screen. Judging by the philosophical ethos running through this film’s silvered veins, one feels the artist would want us to take the situation with a good dose of hope. And so, that is what one shall do, applauding one final poem of the wilderness in all its cold, crystalized glory.

On a final note, all the big cat shenanigans in Snow Leopard made me miss my pet terribly. I’m coming back to you, Maggie, right after TIFF!