The 48th Toronto International Film Festival ended last Sunday, but this coverage continues. Even so, it's time to bring things to a close, so here's the last batch of reviews, all capsules because we're running out of time. They span five continents and a dozen nationalities, comprising a trip around the world through the vehicle borderless vehicle of cinema. Directorial approaches are as distinct as the cultures depicted, from meta-cinematic musings to modern noir, from magical realism with a spring on its step to the slowest of slow cinema. Still, all the works deserve your attention. They are shining gems that prove how, despite assertions to the contrary, cinema isn't dying. At TIFF, it's alive and thriving…

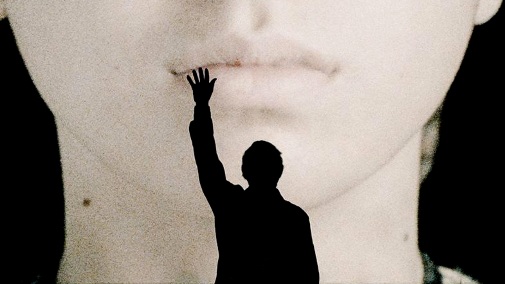

CLOSE YOUR EYES, Víctor Erice

Miracles haven't existed in movies since Dreyer died, but Víctor Erice's latest comes close. His first complete narrative feature since 1992's Dream of Light finds the Spanish master considering the case of a disappearing actor and the erstwhile friend, colleague, and director who looks for him almost twenty years after the fact. What starts as a detective story through celluloid archeology becomes a study in memory, whether it's the fragility of the human mind or the particularities of film as moments frozen beyond death. Though clocking at nearly three hours, Erice's Close Your Eyes flows smoothly, a river of remembrance with currents of deep feeling, a wave of overwhelming wonder that crashes into a finale for the history books. It should sit comfortably beside Dreyer's Ordet and Tornatore's Cinema Paradiso in that account, a sorrowful poem for the seventh art that goes beyond the quaint love letter to reach something deeper, more terrifying than strictly comforting. If nothing else, seeing Ana Torrent again through Eríce's camera is pretty miraculous.

JE'VIDA, Katja Gauriloff

In post-war Finland, Sámi culture faced a state-sponsored dereliction as board schooling was enforced on its youth. In those institutions, children were taught to sever ties with their northern roots, accepting the supposedly warm cloak of Finnish and tossing aside their Sámi rags. In the 1980s, these indoctrination academies were closed, but the damage done to two generations was irredeemable. Director Katja Gauriloff confronts the cultural genocide head-on with her character study of Je'vida rebaptized Iida by the settler authorities. The film, shot in splendorous black-and-white, begins in the depths of grief, as sister and daughter plunder through a dead woman's belongings. For Iida, the process beckons traumatic memories of what she tried to forget. For the younger woman, it's a mystery whose answer remains out of reach. Through flashbacks, Je'vida untangles a ghost story where painful memories are the hauntings of the present time, calling for their lost lamb whose soul was hardened by loss and assimilation.

WOODLAND, Elisabeth Scharang

In 2020, writer-director Elisabeth Scharang survived a terrorist attack in Vienna that claimed the lives of four civilians and injured 23 others. Drawing inspiration from her own experience and Doris Knecht's novel Wald, she conceived a film in which Marian, a city-dwelling journalist, retreats to the Lower Austrian country where her family used to live. The ruined little house by the woods doesn't even have electricity, yet it's rich in whispers of Marian's childhood, a world she left once upon a time to pursue her dreams. Seen as a pariah by the locals, we observe how the writer endures a troubled healing process, PTSD corroding sanity while anger prevails over despondency. Though one might suppose the premise would induce an acting-focused exercise, Scharang is interested in the formalistic possibilities of the forest, letting an expressive sound design dictate rhythms and cuts while DP Jörg Widmer negotiates a bold color story somewhere between subjective realism and stylization. Despite an abrupt conclusion and a stubborn resolve not to linger in trauma but rather its consequences, Woodland represents a paean to self-imposed solitude that, in the end, still acknowledges that we can't do it all alone.

GREEN BORDER, Agnieszka Holland

Breaking from the televisual style that has marked some of her recent work, Polish auteur Agnieszka Holland plunges into the depths of the European refugee crisis, rendering the forest-bound border between Poland and Belarus as a swampy inferno in abrasive monochrome. Her purview encompasses various experiences, starting with a Syrian family and a woman running from Afghanistan who think they'll have an easy time crossing into the EU before their hopes are pulverized under military boots. Later, the camera pursues a Polish guard, complicit in these crimes against Humanity, before finding a civilian turned activist in the face of injustice. Showing the best and the worst of people, Green Border is a harrowing watch that, at times, reaches levels of despair that will make you want to close your eyes and cover your ears. Still, we should look on and confront the truth, including a daring coda whose point may be hard to swallow for some. For this work, Holland won the Jury Prize in Venice but now withstands governmental attacks from the Polish right-wing state. Like the DGA and the European Academy, I stand with Agnieszka Holland. Do you?

LA CHIMERA, Alice Rohrwacher

Perpetually dressed in a crumpled linen suit, Arthur is a former archeologist recently out of jail who makes his living by heeding the call of Etruscan artifacts buried deep within the Italian landscape. The procurement of antiquities forms its own underground economy in Alice Rohrwacher's La Chimera, offering a vision of 1980s Tuscany where everyone's gaze is fixed on the commodification of the past for present profit. Even so, mercenary intent isn't all, and melancholy hangs over the protagonist as he yearns for a lost love and interrogates his role in the grave-robbing trade. Shot in beautiful 16mm by Hélène Louvart, La Chimera is the kind of film whose tactility is so acute one feels like it's possible to reach out and graze the pictured textures, be it the wet soil cradling Etruscan treasures or Josh O'Connor's scruffy chin. Such palpable qualities help set the stage for a final descent into magical realism when yesterday's spirits come a-calling, and we're reminded how, one day, the earth beneath our feet shall be our resting place. What, at first, might seem like meandering absurdities escalates to a poignant ending. Suddenly, every one of Rohrwacher's ideas slips into place, emotional clarity overwhelming as La Chimera breathes its last breath.

BANEL & ADAMA, Ramata-Toulaye Sy

In a Senegalese village where reality and folklore intermingle with no barrier in between, Banel and Adama live an all-consuming love story. So much so that, when duty calls and their intentions diverge, it's as if the apocalypse is near, the fabric of our world rupturing in what might be divine punishment or the plague of a climate crisis. Tradition dictates that Adama must become village chief in succession to his father, but Banel bristles at this, wanting to leave a community that imposes responsibilities she doesn't want to take. Specifically, the young woman does not wish to become a mother. Clashing in sotto voce while their surroundings crumble into dust and rain refuses to come, theirs is a tale where right and wrong are hard to define. Such ambivalence stems from writer-director Sy's respect for ancestral culture even as she questions its effect on the individual who won't conform. Flowing by in 87 minutes, Banel & Adama has all the ingredients for a melodrama but is shot like a primordial manifestation of forces far bigger than us, with Amine Berrada's cinematography rising to the occasion – it's maybe the most beautiful of the entire festival.

MAMBAR PIERRETTE, Rosine Mbakam

After a thriving career in non-fiction cinema, Cameroonian director Rosine Mbakam makes her narrative debut in Mambar Pierrette and, in the process, delivers a masterpiece of African Neorealism for the 21st century. Her documentarian roots are in full display, as she uses non-professional actors to detail some hellish 48 hours in the life of the titular character, a seamstress in Douala played by the director's cousin. This is not mere indulgence in working-class misery, however, with Mbakam paying homage to her character's labor in meditative rite before it all comes crashing down on her. Even then, fortitude prevails, humanistic values and tenets of sisterhood rising above the tides of misfortune. As expected, when it rains it pours, but Pierrette keeps her head barely above water, struggling to stay afloat but steadfast in her resolve. In some ways, Mambar Pierrette feels like a repudiation of similar narratives where suffering is the point. Because, in Mbakam's vision, hardship may be frankly depicted, but there's also defiance in how the filmmaker treasures the small joys of every day, illuminating resilience and strength, odd humor, gorgeous fashions and all.

KANAVAL, Henri Pardo

From the Caribbean to Canada, little Rico's journey is an odyssey that starts on the night of Haitian Carnival, when you don't know who is who and spirits walk among the living. That fearsome evening, in the winter of 1975, a boy witnesses his mother's brutal attack at the hands of anti-communist forces, shocked out of his reverie into nightmare before being swept away from it all, across the Atlantic to a new world. In Chicago, Rico and Erzulie stay in uncomfortable stasis, ultimately embarking on another journey into the snowy recesses of Québec, way up north. While running for their lives, the pair discovers their safe haven might be nothing of the sort, racism and xenophobia a new enemy darkening their days. Director Henri Pardo struggles to find the period specificities in the story, but he's agile in conflating fact and fantasy, dipping his Kanaval into magical realism as an umbilical cord between the displaced youth and the home he left behind. The myths of Haiti shall prevail in this inhospitable land, providing an anchor and a safety net, an everlasting hope that won't be snuffed out. At TIFF, Pardo received the Amplify Voices Award for Kanaval, and considering his bracing picture, it's easy to see why.

LIMBO, Ivan Sen

The settler perspective has long dominated cinema, the seventh art suffering the symptoms of a colonial disease spreading from our historical past to contemporary times. Still, some artists offer a corrective through their work, such as Aboriginal Australian filmmaker Ivan Sen, who, in Limbo, goes to the outback in search of a new form of film noir. The camera follows Travis, a weary detective investigating a cold case in the deserted town of Limbo. There, he uncovers the ghost of genocide and the remnants of centuries-old grief, a system that scarred an entire community with an evil that prevails, undefeated and undeterred. In story, the film recalls Bad Day at Black Rock, but Limbo's style is too unique to allow such a simple analogy. Working as his cinematographer, Sen contemplates an empty landscape violated by so-called progress, broken rock and cavernous gulfs as far as the eye can see, ready to consume the incautious traveler. He shoots in high-contrast black-and-white, taking full advantage of the widescreen frame like few filmmakers in our modern conjecture. It's criminal how Limbo has been ignored since premiering in Berlin - it deserves better.

MIMANG, Kim Tae-yang

In Korean, Mimang has many meanings. It can be the act of wandering, unable to make sense of ignorance. Other interpretations say it's being unable to forget what one wants to forget, while a third definition states it means searching far and wide. Embracing all these readings and offering a fourth possibility, novice director Kim Tae-Yang proposes a beguiling exercise in closely observed mundanity, juxtaposing the changes in the lives of two old friends with Seoul's constant metamorphosis. It took four years to shoot Mimang, mainly around the historical neighborhood of Jongno, through which the cityscape reformatted itself, reminding us of the transient state of everything. A street destined for architectural revolution is like human joy that can curdle overnight into anguish. And yet, for all its sad musings, this is a gentle picture imbued with a delicate warmth, constantly exposing the silver lining of heartbreak. It's also exquisitely shot, using telescopic lenses to condense subject and background, often revealing the city through gradual focus shifts as the characters walk away. Watching Mimang, I felt the solipsistic delusion that the film was made just for me, an intimate present passed from filmmaker to audience.

EVIL DOES NOT EXIST, Ryusuke Hamaguchi

After the triumph that was the epic-sized Drive My Car, Japanese auteur Ryusuke Hamaguchi recedes into smaller-scale storytelling with Evil Does Not Exist. Initially conceived as illustrative filmmaking to fit a track by composer Eiko Ishibashi, the project grew into an idiosyncratic piece whose apparent slightness conceals true radicalism. Wandering through the woods, the camera considers the Mizubiki Village, whose peace is about to be disrupted by intruders from nearby Tokyo. There are plans to turn the forest into the site for a "glamping" tourist retreat, entrepreneurial capitalism in contradiction to the community's way of life. Tackling myriad interests in opposition to each other at a glacial pace, the director weaves a mood piece where opposing perspectives intertwine before unraveling it with a mystifying ending that, a week later, I'm still trying to process. One thing's for sure: nobody will be indifferent to master Hamaguchi's final gesture, a shocker whose ultimate meaning might depend on the viewer. Simmering in a pool of ambivalence, the conclusion demands active engagement and is all the better for it – cinema as a conversation between the screen and the audience.

INSIDE THE YELLOW COCOON SHELL, Pham Thien An

How can this be a feature debut? Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell must be one of the most assured pieces of its kind, announcing the arrival of a new master into the stage of world cinema through a rigorous film whose every shot is a beguiling wonder. Vietnamese director Pham Thien An is the genius behind it all, telling the story of Thien, a young man whose existence is thrown out of its axis when a freak accident takes the life of his sister-in-law and leaves him as her son's caretaker. From Saigon to the depths of rural Vietnam, we follow along as his quotidian bleeds into regret-laden memory, reverie unleashed, and grief setting a path toward transcendence. Frames within frames abound in the film's carefully constructed journey, often joined by choreographed movement that distends and contracts time, diluting our perception of reality even as it presents an uncut version of it - like his character, the director is a magician of sorts. And so, we wander by Thien's side, hypnotized by this slow cinema exercise into a trance that only breaks in watery catharsis. It's the kiss of aqueous silence before the credits manifest the cineaste's farewell. Awe-inspiring is one way to describe Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell, but it doesn't seem enough. Nothing seems enough to describe this masterpiece, this revelation.

I hope you've enjoyed my TIFF adventure and coverage. Stay put for a final installment, with some imaginary awards by a jury of one.