Oscar voting opens today, and, for once, some of my favorites are poised to thrive on the nomination ballot. Because of that, it might seem overkill to write FYC pieces, those love letters by another name. Even so, as it's a time for advocacy, I shall articulate why some of the year's best cinematic achievements deserve to be recognized as such. Today, I find myself inspired to make the case for Lily Gladstone, a virtual lock for a Best Actress nomination who might win it all. And to think some said going lead would ruin her Oscar hopes.

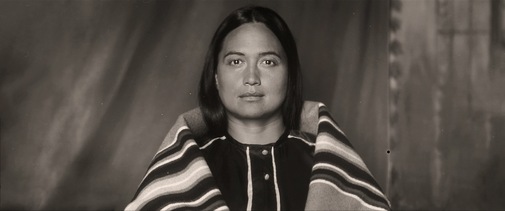

As Mollie Kyle in Martin Scorsese's Killers of the Flower Moon, she breathes life into a dark chapter of American history. Gladstone illuminates the tragedy of a woman and people betrayed, forsaken by individuals who claimed to love them and systems who exploited them under the guise of protection, brutalized by greed and white supremacy…

Before Killers of the Flower Moon ever reaches the tale of Mollie Kyle, a history of cultural schisms and great sorrow has already been established. Perhaps more important to the matters of performance cum character study, it reaches Fairfax, Osage County, through the foot of Ernest Burkhart sometime in the aftermath of World War I. The real-life figure had established himself in town years before enlisting, but Scorsese and co-screenwriter Eric Roth adapt fact to better suit their dramatic intent. Returned from service under military authority, Ernest is quick to fall into another such system of renounced responsibility with his uncle, William Hale, the self-proclaimed King of the Osage Hills.

Despite this trick of structuring befitting the film's trickster noir aspirations, Scorsese made sure his audience met the Osage people before their wealth and before this fool is lectured on them by an autocratic relative. In doing so, the viewer is even more predisposed to notice how the older man presents his information. He describes them as "sickly people. Kind-hearted people, but sickly people." Words dripping with condescension, he projects false grandfatherly affection by repudiating prejudicial dismissals of their character. "The Osage are sharp. They don't talk much (…) Just because they're not talking don't mean they don't know everything about everything." It's a sprinkling of sugar to mask the taste of poisoned gin.

And yet, this warning regarding silence is a fair point. In the book on which the film is based, David Grann mentions how white people were prone to interpreting Native people's taciturn nature as a sign of dumbness, mayhap even soullessness. They used it as another tool in rationalizing hate, justifying their prejudice and its dehumanizing conclusions. So, while we might want to turn away from everything Hale says, the Devil sometimes speaks truth as part of his ploy. Certainly, we shouldn't take on the Osage silence as a sign of inferiority. In Scorsese's late cinema, silence is a multifaceted idea that can be as terrifying as it is ennobling.

Indeed, when adapting Shūsaku Endō's Silence, the director would have done well to remember its value. In that production, narration is a constant, verbalizing what the actor's wordless work had already telegraphed.

This redundancy remains my greatest issue with a film I otherwise love, so I feared a repeat of it going into Killers of the Flower Moon. But Scorsese has chosen a different approach. Hale and Ernest reveal who they are in their lies and half-truths, quickly talking themselves into a corner of the audience's moral judgment. On the other hand, Mollie is permitted to exist in her silence without needing to have everything inside her explained through text. In a beautiful beat of paradoxical filmmaking, this doesn't preclude Gladstone from talking over the moving image. When we finally meet Mollie, she's speaking to us in voice-over narration, a privilege no other character gets.

While there's great depth in silence, I can't complain about being introduced to Gladstone through one of her key weapons as a performer – that melodious, measured voice of hers. Hearing it now, so directly, will make its progressive absence all the more intolerable. But what about what's said? She delineates the fate of her people over tableaux of death, the brutality of killing contrasted with the victim's repose under funeral rite. At times, we even glimpse the murder happen as she declares the case shut by authorities and deemed suicide. There's such exhaustion in the sound of her telling, a bone-deep sorrow in every syllable. It's like a slap when her entrance leads to "I'm Mollie Kyle, incompetent."

It's the first line she speaks within the film's reality, engaging another person rather than the camera and the audience beyond. The language is blunt, an act of self-humiliation demanded by the powers that be, a formality in the racist system she inhabits. However, though the act is denigrating, both Mollie and Gladstone keep their dignity. It's a powerful introduction that beseeches the viewer to read into the words unspoken, the poise and passive resistance of Mollie. Notice how she swallows any objection against the man who's got her fortune under his thumb. At the end, there's a suggestion of a smile, some placid performance of acquiescence that'll put the white authority at ease.

To him, it corroborates her incompetence and childlike helplessness. To us, it's a knowing, unknowing smile, a façade of serenity that's more strategic retreat than capitulation. Even more than her oft-silent and silenced words, Mollie's smiles are a precious commodity within Killers of the Flower Moon and help erect the arc of her undoing, resistance, survival. Early in the picture, they're more common, even if not always sincere. She seems honestly content at Osage ceremonies, but those grow fewer and far between as the Native population is violently cut, their customs gradually receding into the background, unseen. Even when her sickness worsens, Mollie still smiles in Osage ceremony and Christian church.

Her genuine smiles reach her eyes. Her polite ones never do. It's a distinction that becomes obvious when, after that bit of painful bureaucracy, the viewer gleans the first meeting between Mollie and Ernest, working as her cabbie. She doesn't take his offered hand getting into the vehicle as she'll later do, a sign of early reticence when dealing with this white man, new in town and thirsty for riches. But as the ride continues and more rides come after, she relaxes, perchance amused by Ernest's dimwitted openness and bad jokes. Whether it's a smirk in the rearview mirror or a face-to-face grin, Mollie is gratified by the man's presence. What he looks like to us is immaterial as long as Gladstone can convey the layers of attraction falling into infatuation.

He's simple and boyish, flat-footed clumsy, so open about his mercenary intent that the unsubtlety tastes like accidental honesty. Even if the viewer can't appreciate it, she sure can. He counterpoises the innate seriousness of the responsible daughter we'll know her to be, the put-upon sister who's stalwart and believes diabetes will take her before her time. Furthermore, Ernest's dimwitted blasé nature almost seems to give her security. She's smarter than this lazy man whose lack of substance will mean he's not as likely to run around or walk over her. Or so the movie's Mollie would think. The character flaws that make him an agreeable partner are central to his evil. So, though her smile is knowing again, in the broader context, she doesn't know what she's getting herself into.

From the car to church and back again, to her house, where they have a first date of sorts. I'll be honest: this after-dinner sequence is my favorite passage of Killers of the Flower Moon, maybe of the entire cinematic year, culminating in a demand for quiet while the sounds of nature clamor over the smallness of Man. But there's more to it, such as the ways in which their interaction develops the chemistry that arose in their car-riding scenes. And new depths come forth. Please pay attention to a hint of resentment in Mollie's expression when mentioning her mother. It's nothing but a side-eye, just a slight movement, a touch of anger to be echoed later when facing the older woman's displeasure. The actress fleshes out a personal history beyond the film's narrative, expanding under its frame.

Though saturnine, Mollie reveals much about herself in a conversation that, on paper, might feel like a two-sided interrogation. But Gladstone plays it like a candid negotiation of intimacies with a potential beau. As a performer, she's excellent at acting attraction and fondness, suggesting the depth of emotion the text eludes. In my eyes, it's not a script deficiency but rather a trust in the actress. Through Gladstone, we see Mollie letting him in, little by little. And there's yet another reality making itself known on the margins of these scenes - she likes to be wanted. More specifically, she likes to be wanted by a white man and all that promises. Kissing in the car, she'll contemplate how his pale hand looks over her darker skin, and Gladstone lets a note of wonder intrude upon Mollie's sensible voice. If there's a facet of fetishization to his desire, she lives with it in a most familiar compromise.

The scene of the sisters talking about their men after church is another crucial moment of lightness before the shadows close in and snuff all that's joyful out for good. It tells us what we need to know about Mollie's complicated feelings for Ernest at the onset of their romance. This time, it's not something to be gleaned from performance notes and context clues – it's plainly stated in the text. She likes his blue eyes and finds him handsome, even as the sisters disagree and see more beauty in his brother. Sure, Mollie recognizes his mercenary wants, his desire for money, but she appreciates his supposed need to settle. She sees him as a coyote she can tame or live with regardless. It's the pragmatism in her. It's the naivete. These are confidences shared between sisters in the Osage tongue, laughs and gentle teasing lacing their communion with warmth and familiarity.

When death comes knocking, the memory of that temporary happiness will be lemon juice poured over an open wound.

First goes Mollie's sister, Minnie, and Gladstone refuses to underplay grief. She cries, shouts, and breaks apart, sharing the pain across the camera and the screen. Then, Anna is dead – killed – and seeing her body, Gladstone conveys Mollie's horror as near catatonic. There's the idea she's going to throw up, but the actress plays the sickness like something kept barely under control. As an autopsy out of one's worst nightmares gradually manifests, Gladstone disconnects Mollie from what's happening. At the height of affliction, she covers her ears and rocks, a traumatized woman trying to lull herself into an impossible peace.

In a new confession to the viewer, Gladstone's voice speaks of an anger consistently sublimated in stares and the tension of maintaining composure. Throughout tribal council and attorney talks, Scorsese and Schoonmaker keep cutting back to the actress' face as other characters talk over Mollie, examining the visage of one who's losing everything. "This evil around my heart comes out of my eyes," she says, and we can see it plainly. She's a body wrecked by sickness, a spirit consumed by paranoia, and in this nightmare of an existence, Ernest becomes her support. It's a horrifying reality, but that ugliness doesn't make it any less accurate. The filmmakers don't overexplain, they let you absorb the treacherous emotional web of the characters and make your conclusions.

Part of it is an admittance of our limitations when looking at history. We have records of Mollie and Ernest's relationship, but the truth of their hearts will always be unreachable. The film lets us get close while denying the arrogance of presuming to expose all of their mysteries. And yet, how could we be closer to the film characters than in the secrecy of their bedroom, watching how the husband assuages his wife's pain with sweet lies and untruths he might think true? Right after questioning the man's love, Mollie will smile and allow herself to get pulled into an erotic embrace. Fueled by the actors' chemistry, this portrait of spousal harmony is both affecting and infuriating, for it looks like love but surely can't be. Let that thought eat you from the inside out.

At this point, smiles have become rare to the point one questions if they're really there whenever the camera catches them. At the doctor's office, for instance, Gladstone is a bottomless pit of caution when talking to the medicine men, only ever trading in softer expressions with Ernest or their children. The actors establish different levels of trust as if building a house of cards to be brought down most terribly when Mollie finally accepts the misplacement of her heart. But there's a long way to go until then. The first suspicion explodes in the only argument we get to see between the married couple, when a weakened Mollie tries to reject the doctors' insulin injections. Mostly verbalized in un-subtitled Osage, we don't need the words to understand the rhapsody of doubt and fear roaring between the actors.

Scorsese trusts you to pay attention to her tone and face because her ultimate, wordless resignation is where the cinematic "truth" lies. She must believe Ernest when he proclaims his love, that the medicine is for her health, that he'd never hurt her. What else can she believe? That she's powerless and her whole life's a lie? That she let herself live with the murderer of her kin? Like a displaced preamble to Mollie's last scene, Scorsese and Gladstone invoke the possibility of guilty feelings beyond Ernest's conscience. Part of her ultimate acceptance, taking the injection like her husband wants, is also a consequence of exhaustion. At a certain point, one grows tired of fighting. Better to give in than keep speaking up for oneself and suffer just the same.

It's easier to capitulate than inspire hatred in the only person still there for you, loving you. There's a movie's worth of marriage stories happening in one scene, a tale of conflicting self-delusions and despair in the face of abuse. Now, I know I am bringing a lot to the proceedings as someone who read the book beforehand, got intrigued by Mollie Kyle's story, and has a personal history that might echo through portrayals of toxic relationships. However, I also believe one must credit the artists at hand for inspiring such reflection. Despite what others have criticized about the film's decentralizing of Mollie, scenes like this make a thousand thoughts rattle in my head and feel, if only for a moment, that I got Mollie or at least Gladstone and Scorsese's version of her.

Outside the chamber drama, death keeps coming, and with each funeral, a part of Mollie erodes away. Rather than play an anesthetized stupor, Gladstone continues to let grief affect the character in ever-growing waves. Each new loss is a crack in the foundation of her personhood, her poise. Even the ghost of a demise yet to happen seems to sneak up on Mollie. It's the unspoken tension Gladstone exudes in the presence of William Belleau's Henry Roan, a childhood fiancé according to Osage tradition. When news of his demise reaches her, there's no surprise or shocked reaction. Instead, there's a pause, a question - "Was he murdered, or did he kill himself?" Tears come first, but they dry quick, but the proffered doubt lingers. The sound of her words may not reverberate on the soundtrack, but it sure does inside the viewer's head.

As does the scream she lets out when Mollie's final sister dies in an explosion. While the camera keeps its distance, Gladstone wails and crumbles, as if daring us to look away or cover our ears. It's sorrow and it's fury, tangled up and aflame, doused in gasoline for good measure. Maybe because this scene is so lacerating, Scorsese lent his version of Mollie a shred more agency than the real woman had in life. Her trip to Washington to appeal to the government for federal intervention in the Reign of Terror is fictitious. However, it lets us consider Gladstone's characterization at the height of despair but still active enough to take action. As the poisoned insulin takes its toll in the following hour of film, we'll fondly remember a time when Mollie could do such a thing.

At church, proclaiming she's afraid of being in her own home, Mollie almost looks lost in some somnambulistic daze. Gladstone contains a horror film within Killers of the Flower Moon. This could be an Ethel Barrymore situation with all the stodginess that entails but instead reads like an existential apocalypse, visceral to the nth degree. You have to admire the complete surrender of Gladstone to Mollie's physical decline; the corrosive nature of Ernest's love manifest in undeniable visual terms. It's sweaty and disjointed, far from notions of idealized martyrdom. One could expect another conclusion from the Catholic mind of Martin Scorsese but, just like in Silence, Because, we're made to see there's no inherent nobility or spiritual valor to suffering. It's pain and pain alone.

On the brink of death, Mollie's rescued by the FBI men after Ernest's arrest, and we see glimpses of her recovery, lost in the flurry of montage. From the physicality of someone learning to walk again to a supervised reunion with her husband on a field, the woman's marital trust starts to seem obscene. In any regard, it's upsetting to witness, and one begins to search for clues of wariness in Gladstone's portrayal. They can mostly be spotted by comparison, by weighing her tone in scenes past, such as when Mollie asked Ernest if he feared his uncle during their dinner date. Now, when she asks similar questions, a new keenness emerges, her stare more doubtful, eye contact wavering slightly. These are the dying embers of trust. Watch them die when Ernest Burkhart finally admits to his crimes on the stand.

Throughout the film, Scorsese and Schoonmaker have used Gladstone's muted reactions as a central factor in the film's storytelling strategy. At points, those reactions gained another value as one came to sense certain moments as manifestations of Mollie's perspective. Take the wandering camera peering at white people's faces at the train station and during baptism, paranoia given film form. Take the fiery interlude that comes across like a Witch's Sabbath, hell on earth as envisioned by the Christian imagination. And here we must remember that Mollie, not Ernest or Hale, is the one whose spirituality is more in tune with the camera both because of her Osage tradition and Catholic faith.

At the final trial scenes, the image cuts to Mollie at precise points, confronting us with her own confrontations – not just with the culprit, but with the facts, with her ignorance of what was happening. The flashbacks to Anna's death are as much the killer's mind as Mollie's imagination, harrowingly couched in the image of her gently putting a pillow under the killer's head. Then, her eyes are fixed on him during Ernest's second testimony. Even when the prosecutor brings the jury's attention to Hale, the cutaway to Mollie reveals her eyes never leave Ernest on the stand. Judgment, hope crumbling, love rotting away within her steely gaze beneath a shroud of unshed tears. She only ever wavers when he proclaims his love. Gladstone's Mollie can't stand to stare at that love anymore.

Thus, we come to Mollie Kyle's last scene in Killers of the Flower Moon, a culmination of Lily Gladstone's performance and final testament to her shattering achievement. For me, it's sublime.

Entering the room, Scorsese's lens observes us as it tends to do. She's the most beautiful person in existence. She's the Virgin Mary in Osage blankets. Her words cut through his panicked babbling like a hot knife, sizzling as Mollie reminds Ernest of their daughter when he only asks about their white-passing son. Instead of steeliness, Gladstone works within a register that's almost too soft for comfort, a despondent exhaustion that's never been so pronounced, not even near death's door. Something broke inside Mollie, and it's dolorous to hear, to see, to experience. Hers is a symphony played in minor key, reaching the most desperate coda as Mollie asks her husband if he has been poisoning her with the injections.

This, right here, is the final destruction of their bond, so central to Killers of the Flower Moon. It's not Mollie giving him a chance at redemption, though. It's Mollie coming to grips with the reality of his hollow love, that this is a man for whom nothing's sacred, and what that means to her as a devout Catholic whose feelings on guilt and blame, on salvation, are shared by many of Scorsese's heroes and lost souls. Ernest's denial is worse than his admission. It takes away the possibility of truth to their supposed union, because it spits in the face of their vows, their devotion sworn under two faiths. As an epic draws to its close, Mollie is the last person standing and wrestling within themselves, for she's the only one capable of examining one's soul and existing within the silence.

Lily Gladstone keeps it inside, a storm of disappointment suggested by her gaze and little else. Serenity prevails, even if only on the faintest of surfaces. Her physicality is as quiet as her symphony, minor-key and stately, still haunting despite it all. And in memory, her performance shall remain colossal, a cathedral.

Disdainfully looked down by the camera and the woman he swore to love, Ernest is left alone, and Mollie exits stage left. There's no absolution, only a dark tale to tell and imperfectly share, to reckon with for perpetuity.

In this exhaustive analysis, I hope to have explained what makes me love Lily Gladstone's portrayal of Mollie Kyle so much. Moreover, I hope you glean how that portrayal is constructed not just by the actress' work but by a whole network of textual and directorial decisions, precise cutting, and framing. I believe that, though many writers I admire think otherwise, Mollie Kyle in Killers of the Flower Moon is one of the year's best and most fascinating creations. Honoring the historical person is a responsibility so great as to be unreachable, and Gladstone, Scorsese, and all others did an admirable job. At the very least, they created great cinema. Feel free to disagree, but I must remain faithful to this truth of my own.