No two people feels the exact same way about any film. Thus, Team Experience is pairing up to debate the merits of this year’s Oscar movies. Here’s Lynn Lee and Cláudio Alves on American Fiction...

LYNN LEE: Hi Cláudio - looking forward to a friendly fisticuffs (is there such a thing? at TFE, yes!) on American Fiction, one of my favorite movies of 2023.

I have to admit I'm a little self-conscious about ranking it so high in a year filled with noteworthy films. It wasn't a cultural behemoth à la Barbenheimer. It's not the work of a known auteur or a rising one; it doesn't have the weird-cool vibe of a Poor Things or the wistful-cool cachet of a Past Lives. Visually, it's not particularly interesting. Thematically, it follows in the footsteps of other, similarly themed movies about Black artists confronting racial pigeonholing and stereotypes - from The 40-Year-Old Version to Bamboozled all the way back to Hollywood Shuffle - but made significantly more palatable (I won't say diluted) for mainstream audiences...

Indeed, for an indie film, its appeal is squarely what I call "audience award" appeal - broad, easy to enjoy, satirical but not too edgy. The kind of middlebrow movie your average film festivalgoer or moderately liberal, educated American viewer would feel totally comfortable with, maybe even pat themselves on the back for enjoying. Ok, so then why do I love it? Three simple reasons:

1. It's really, really funny - no other movie I saw last year made me laugh so much. The humor starts out pretty dang broad, but develops more nuance as the film goes on and becomes as much a character study as a satire of American cultural gatekeepers (if not more so).

2. By the same token, the film skillfully modulates between the satire and the emotional drama - even tragedy - of the protagonist's "real" life. Not only does it play successfully in both registers, it connects them in such a way that each half of the story provides revealing commentary on the other. I haven't read Erasure, the Percival Everett novel it's based on, but for my money Cord Jefferson does a brilliant job transferring to film what I assume is Everett's main narrative/metafictional trick: using the satire as a vehicle for the upper middle class black family drama he actually wants to write about.

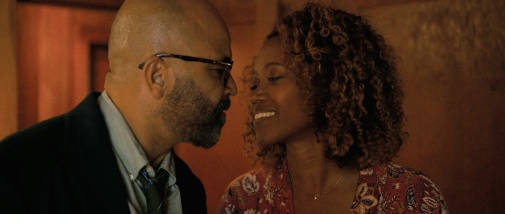

3. Jeffrey Wright. Best performance of his career - he was made for the role, and the role was made for him. The rest of the cast is terrific as well - this is true ensemble acting at its finest. Like the film as a whole, the characters run the gamut from comic to poignant, and everywhere in between, and yet the whole thing feels remarkably cohesive.

There's my gauntlet. Now tell me why I'm wrong - but at least please tell me we can agree on Jeffrey Wright?

CLÁUDIO: We can agree on Jeffrey Wright, who'd be my winner pick out of that Best Actor lineup. Indeed, I love almost everyone in the cast, with one notable Oscar-nominated exception. Since I'd like to start with some positivity, I'll shout out my two favorite turns beyond Wright's multi-layered curmudgeon. Despite not looking at all like Wright or any other actors playing her family, Tracee Ellis Ross makes us believe the sibling relationship and all its complexities in the brief time she's on-screen. If we feel the impact of her absence, it's because Ross left such an indelible impression. And then there's Erika Alexander, a true revelation despite the decades of work behind her. At times, I yearned for a film solely about the relationship between Monk and this new paramour who brings such light into the movie yet never feels idealized or flattened, having ample wiggle room to modulate tone and leave with a sting that hurts.

Maybe because I was so besotted by Wright's work and chemistry with the likes of Ross and Alexander, I was also disappointed every time the film abandoned its family melodrama to, once again, focus on its outdated, defanged satire.

I read Erasure, and part of my dislike of American Fiction stems from that. The book is squarely fixed in time as a piece born from industry observations and cultural touchstones of the 80s and 90s. It's also much more biting, daring to name real authors, to explore the thorniness of Monk, make stabs at political commentary beyond the issues parodied in the success of My Pafology, the legitimateness of writing models, the web of compromises between art and commerce, etc. It does it all through remarkable structural gambits that play with literary form in ways this film isn't even interested in translating or just exploring in film idioms.

I can't argue with your first point since the success of comedy is so personal and subjective, and I agree with that third point up top. However, I find myself at odds with your second reason and incredibly frustrated that Cord Jefferson may be about to win a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for his writing.

LYNN: I defer to your knowledge of Erasure, though what you say sounds consistent with what I've read about it elsewhere - that it was very much in response to particular literary phenomena at the time (e.g., Push), and that it's more acerbic and more meta than the film. I disagree, though, that those differences make American Fiction's humor toothless or somehow less relevant. First, even if the particular cultural triggers that inspired Erasure are from a quarter century ago, the broader questions are just as timely, indeed timeless: what is "authenticity" in an ecosystem where both the gatekeepers and the creators are driven primarily by what sells? What standards and what compromises are acceptable?

The film's cheapest laughs are obviously at the expense of the (white) publishers and even crasser Hollywood execs blinded by the dollar signs in their eyes (though I admit I guffawed loudly at "Plantation Annihilation" and Monk's entire first meeting with Adam Brody's producer), but there's a deeper irony here that's embodied in the gradual erosion of Monk's superiority. I liked that his convictions are challenged by those he considers himself superior to, whether consciously (Issa Rae's rival author) or subconsciously (Erica Alexander's love interest). The movie, at its core, is really about Monk's coming off his high horse, to great comedic and dramatic effect.

As for the novel's structural devices, I'm curious how you think they could have been better transferred to film. I'm envisioning Charlie Kaufman-like shenanigans, and not convinced they would have enhanced my enjoyment of the movie or the evolution of Monk's character. But then, a little meta goes a long way for me; as it is, my main reservation about American Fiction is its ending, which comes off to me as a bit of a narrative cop-out. As a nod to Erasure's framing, it does feel inadequate, even half-hearted.

Finally, on a more positive note, I'm glad we both agree on (most of) the acting. But I'm going to push you a little on Sterling K. Brown. While he wouldn't make my own best supporting actor lineup, I think he's very engaging and adds both warmth and humor to the family dynamic. What about his performance do you dislike? Is it that he's not convincingly gay, or that his coming out is used for comedic effect? Does his character even exist in the novel?

CLÁUDIO: Cliff is in the novel, though much of his character is contained within flashbacks. So, Brown had a similar challenge to Ross, needing to suggest a complicated family history that the film keeps off-screen. Only, I don't think he solves the problem. Instead, Brown comes off erratic, a script mechanism rather than a proper character. And yeah, I think the film's portrayals of queerness are broad to a detrimental degree. Maybe not Brown's performance alone, but the context within which Cliff exists. Those two coked-out twinks wearing speedos to a wedding are eye-roll-inducing. In a film whose premise stems from questioning racial stereotypes commercialized to a white audience, the use of gay stereotypes for a straight viewer is almost self-contradictory, verging on plain hypocrisy.

LYNN: No argument on the gay stereotypes of Cliff's two beach house "guests" - it's a lazy joke the movie didn't need. Unlike you, though, I don't think the thinner writing of Cliff diminishes Brown's portrayal of a character who, in a different way, seems as lost as his brother. The part of the ending that does work is the reconciliation of these two, joined by their mutual recognition that they've both still got a lot of work left to do on themselves.

CLÁUDIO: I definitely agree that the best part of the ending(s) is the hint of reconnection between the brothers. Still, I can't help but wish for a version that earns that emotion more fully, through a characterization of Cliff that actually rings true.

Regarding datedness, it's more than the fact Erasure is a response to cultural objects of its time. I'd argue Push, among others, is still a relevant touchstone in 2023 and should have been named like it is in the novel. Percival Everett's Monk is much more of a satirical hack than the one in the movie, and that portrayal allows him to be in dialogue with works he despises but the reader might not. It risks alienation in a way the film never does. Indeed, American Fiction is eager to make the viewer comfortable, pretending to confront when it really just coddles.

But the dated-ness extends past those references. Simply put, Everett conceived his novel within a specific milieu of the academic and literary worlds at the time of writing. Apart from a cringe-inducing opening, American Fiction barely glances at Monk's particularities as an Academic and starts with a teacher-student interaction that feels false, almost disingenuous. And then, the apparatus surrounding the Stagg R. Leigh persona is weirdly anachronic, with nary a mention of social media and the new ways authors have to sell themselves. The publishing industry has changed in the past two decades, but Cord Jefferson doesn't seem to think so.

LYNN: Huh, I thought the opening scene was spot-on in capturing how out of step (though not necessarily wrong) Monk is with his times. That classroom interaction, followed by his meeting with the concerned faculty afterwards, efficiently sketches the main outline of his character, which Wright spends the rest of the film filling in so ably.

CLÁUDIO: Honestly, it's probably impossible to make a faithful adaptation of Erasure that keeps its structural devices. The book is peculiar, including the entirety of My Pafology, mixing essays with epistolary passages, and at one point even having the fake Leigh as our commanding perspective on the real Monk. That said, I'd expect the film to be more playful than it is, transforming from scene to scene. Do the wild swings in cinematic terms, break stylistic idioms and destabilizing the viewer.

The two stabs at something like this – the My Pafology writing session and the multiple endings – feel too little too late. In the latter case, it's like the cop-out incongruence you describe. And even then, formalistically, everything is so damn uninteresting. The filmmaking is solid but never more than that, lacking in audiovisual boldness throughout. This material deserves boldness.

LYNN: Your last comment on boldness encapsulates our differences. You think American Fiction goes out of its way to make its viewers comfortable rather than challenging them. I don't actually disagree with that, I just have the obverse reaction: I'm impressed Jefferson was able to make a prickly story go down so easily and breezily. Could he have taken more risks? Sure. But would the end product have been as coherent or, frankly, enjoyable? I keep thinking of Bamboozled, one of Spike Lee's best and most underrated films. It's hilarious and incendiary and very angry in a way that Jefferson clearly isn't.

It also goes off the rails at the end, when Lee runs out of narrative options other than to literally kill off his guilt-racked, self-hating protagonist. (That option is played, instead, as a joke in American Fiction.) Jefferson's satirical vision is gentler and more tolerant than either Lee's or Everett's. In some ways, that makes it a more effective vehicle for the underlying message: the Black American experience contains multitudes, which have little to do with preconceived notions of marketability.

CLÁUDIO: It's interesting that you bring us back to Bamboozled as a point of comparison because that's a much better film in my eyes. Moreover, it sparks discomforting notions, that defies and forces deep thought in ways that American Fiction never even approaches. Jefferson's film got some chuckles out of me, but it never made me reconsider anything about its themes, nor did it leave me reeling with what I'd just watched. If anything, it confirmed things I already thought, like the aforementioned pat on the back. And I don't usually want a pat on the back from cinema, especially that which announces itself as a political object, as a provocation.

That may be why I felt the melodrama portion of the picture felt richer. Sure, the socio-economic specificities are underexplored, but there's more honesty in any given Alexander-Wright exchange than in the whole literary industry plotline. But even then, the audiovisual aspects aren't any better. What did you think of that facet of the film? Are you as annoyed with the Oscar-nominated score as I've seen some folks? I liked the music, though not enough to nominate it.

LYNN: Oh, I'm not going to bat for the visuals. Form's definitely following function in that department - there are some funny sight gags, and a reasonably thoughtful evocation of the Ellison family's fraying privilege, but nothing to write home about. As for the music, I'm the last person to ask; I'm not even joking when I say that I remember, on average, one film score a year. This year it's Poor Things (plus maybe that recurring motif from May December, which isn't even an original theme). It certainly isn't American Fiction, although I did revisit the soundtrack when it got that surprise Oscar nod. It's a pleasant enough nod to Monk's namesake, I guess.

But as I indicated at the top, aesthetics aren't everything. I love American Fiction for the characters, the acting, and, yes, the writing. I love its comic energy, its humanity, and its expert control of what in lesser hands could have been very discombobulating tonal shifts. (It's no coincidence that I mentally pair it with another favorite of the year, The Holdovers, for very similar reasons.) It's crafted to please, but not to pander. That's a hard balance to strike, and one that's becoming increasingly rarer in our current filmscape.

CLÁUDIO: We'll have to agree to disagree on that pleasing vs pandering dichotomy. I know I came out of American Fiction feeling more pandered to than necessarily pleased. Still, I'm glad others can find so much to love in a work that obviously meant a lot to its makers. Cord Jefferson's Spirit Awards speech was proof enough to make me less hostile toward a potential Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar win. Still, going into the 96th Academy Awards, I'll be rooting for Wright from the American Fiction team and no one else. If only Erika Alexander had been nominated.

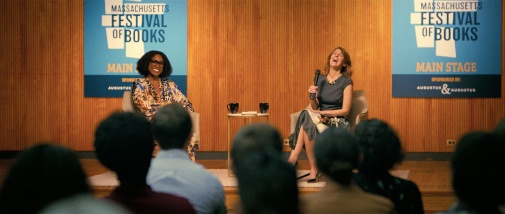

LYNN: Jefferson's definitely been a natural on the Q&A circuit, which is buying him a lot of goodwill - interesting to see if it's enough to sneak one trophy away from the Oppenheimer juggernaut. Though if it makes you feel better, Cláudio, I'm pretty sure Oppenheimer is taking Adapted Screenplay in its march to Oscar dominance, which means American Fiction likely walks away empty-handed. For actor, Cillian Murphy is looking increasingly inevitable; only Paul Giamatti still has a sliver of a chance for an upset. (In my dream world, Giamatti and Wright would tie for the win.) I just hope AF's nominations and any clips they show at the ceremony are enough to induce more people to see the movie - to appreciate Wright's performance, if nothing else. May it bring him many more meaty, funny, three-dimensional leading roles!

CLÁUDIO: Hear, hear! May the world wake up to the genius of Jeffrey Wright, even if it’s through American Fiction. The man has what it takes to be a leading man movie star, so let’s start giving him the opportunities he deserves.

Previous Split Decisions: