Apologies for the delay in what was supposed to be the Almost There series' glorious return. Since the Oscars are less than one week away, let's see if I can get things back on schedule, starting with a look at one of the season's most disappointing "snubs." When May December premiered in Cannes, many singled out Charles Melton's performance, starting a narrative with great potential. Here was a Riverdale heartthrob making his way into the big leagues, proving he could go toe to toe with such awards-winning stars as Natalie Portman and Julianne Moore. Sadly, not long after a Gotham victory, Melton's campaign lost steam, victim of his film's failure to secure industry support, and he ended outside of AMPAS' Best Supporting Actor ballot…

Inspired by the Mary Kay Letourneau scandal, May December isn't a direct dramatization of the real-life story. Instead, it's another of Todd Haynes' experiments on the complicated relationship between cinema and truth, depiction and exploitation, the medium's limits and its vampiric properties. Keeping faithful to the director's past projects, it's also a sudsy melodrama dripping with meta-textual analysis and a certain air of obscenity. Many have debated if it's right to call May December a comedy when it depicts such serious issues, but part of the film's game centers on that discomforting dynamic.

Working from Samy Burch's Oscar-nominated script, Haynes makes the viewers squirm in their seats. Moreover, those deliberate dissonances in tone extend to how he manages his leads. As Elizabeth, a classically-trained trash TV star trying to gain indie film cred, Portman is the mirror as hungry void, a carnival looking glass dripping with artifice. As Gracie, the Letourneau stand-in, Moore walks the line in the middle of stylization and self-delusion. She feels dangerous and more psychologically "real" than the woman studying to play her. Finally, Melton plays Joe, Gracie's underage victim grown into her husband. He's the human cost to the women's cruelty, the pain beneath the camp.

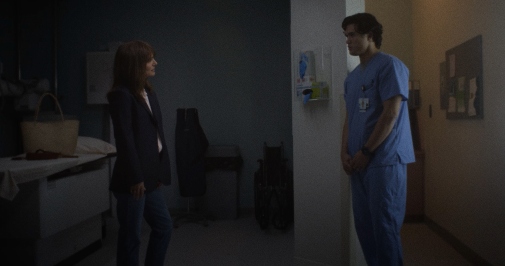

He's also a beacon of bruised naturalism within May December's melodrama, a contrasting force that punctures the stylistic construction of everything and everyone else. Melton enters the film like an adolescent in a grown man's body, hunched like a kid with bad posture trying to make himself smaller. It's as if he senses the camera's gaze and shies away from it. Toward his wife, he's deferential in the way a boy reacts to his mother's command, an uncomfortable gesture that signals all that's wrong with their marriage from early on. However, when Elizabeth shows up, the performance of adulthood takes center stage over the insecurities of arrested development.

Shy and soft-spoken, his is a detailed characterization that spends the film's first act as an object to be spied upon, examined, dissected from a distance. The closest we get to Joe in these early passages are silent moments caught up in an anonymous text chat, or the glimpses into his work with butterflies. There's a gentility to his touch but also an air of comfort that's conspicuously absent whenever he's with company. Such contrasts, primarily manifest in the actor's physicality, give us enough information to see through the illusion of Joe and Gracie's domestic idyll. For example, his passive demeanor in a family dinner shared with Elizabeth plays like some hushed perversity, a subtle disruption in sync with Haynes' disruptive direction.

It's not just body language, either. Trying to talk with the actress by himself, Joe is all broken sentences and clumsy deflection. His eyes are constantly circling about, looking for somewhere to look that's not the woman's visage. Whether in the driveway or the workplace, his face is as nervous as his voice, denouncing how Joe perceives the interactions to be somewhat illicit. And yet, when the pair's stares connect, we find ourselves witnessing a lamb seeking comfort in the lion's leer. It's horrifying to think so, but Melton performs Joe as more comfortable seeking affection from the opportunistic stranger than he is with his father. When together with the older man, it's all saturnine stoicism.

The developing chumminess with Elizabeth – best seen when Joe talks about his butterflies or walks the dogs – is juxtaposed with old tensions reaching a breaking point between husband and wife. Consoling Gracie in the middle of a breakdown, he's reticent, quasi-timorous. At the same time, one gets the impression such scenes are commonplace in the home, to the point the consolation is akin to a well-rehearsed performance. Here, he's a kid giving solace to a crying maternal figure. He's the boy forced into premature adulthood – the man of the house – who never got to grow into that role. I hesitate to use these words, but Melton plays Joe like somebody fundamentally broken. This story is his tragedy.

Listening to how others describe Joe within the narrative, you also understand his part as a recipient of people's expectations and presuppositions. The quiet confidence others project onto him says more about them than the man himself. Even when being a father to his kids, you sense a camaraderie mixed with unsureness, more typical of a big brother than a patriarch. It's heartbreaking to watch Melton navigate through these truths, these contradictions, coming to an emotional boiling point in the film's last act. It starts with Joe sharing a joint with his college-bound son, a scene on the verge of farce if not for the undercurrent of horror, including the way this kid seems more mature than his father.

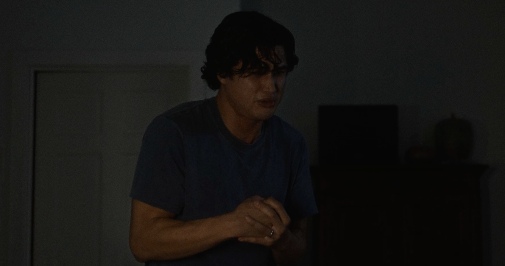

On a purely technical level, Melton aces the intoxication, making us keenly aware of how much Joe is trying to be serious and articulate his feelings as words escape him. Lost in the transition of laughter into sob, his earnestness hurts. Later, alone with Elizabeth, that sincerity manifests again. But now, it collides with insincerity made flesh, and a love scene unfolds like a trap. Portraying Joe's carnality stuck in a teenager's abruptness, Melton sets the stage for one catastrophic afterglow awakening, when Elizabeth hits him with the year's most lacerating line: "This is just what grownups do." There's no genuine feeling, no pity from the actress, or even a basic understanding of what he's going through. So, Joe crumbles.

Words come out of his mouth like water from a misshapen teapot, stops and starts, glugs and splashes. At home, breaking apart for Gracie, Joe's body begins to seize as much as his tongue, stuck in pleading positions and bereft of any support. With his rawness, Melton punches through all the film's many artifices and confronts us, the audience, his fists bleeding. Actor, text, directorial tone, and audiovisual setup function in symbiosis, even when they are contradictory between them – a miracle of bruising cinema and Melton's craft. Coming down from that for the character's last sequence, one's left lost, yet aware of the façade Joe puts on for his kids who are moving on with their lives while he remains stuck. Hopefully, they will have the future Gracie took from him. When no one's looking, he cries, and we are intruders once more. It feels wrong to look, but we can't look away.

Beyond regional critics honors, Melton's biggest get was a Gotham Awards victory against such strong competition as Best Supporting Actress juggernaut Da'Vine Joy Randolph. He was also nominated for the Critics Choice Award and Golden Globe, hitting two of the big four precursors. Later, he was also nominated for an Independent Spirit Award, which would have meant nothing once upon a time. However, they're very Oscar-y nowadays. AMPAS didn't follow suit, nominating five other men over Melton. They are Sterling K. Brown in American Fiction, Ryan Gosling in Barbie, Robert De Niro in Killers of the Flower Moon, Mark Ruffalo in Poor Things, and likely winner Robert Downey Jr. in Oppenheimer. Though I consider him a lead, I'd say Melton is superior to the complete quintet. I even prefer him to the five Best Actor nominees.

May December is streaming exclusively on Netflix.