Since 1939, Gone with the Wind has been re-released countless times in American theaters. This year, it's enjoying another of those on April 7th, 8th, and 10th to celebrate the picture's 85th anniversary. While defined by gross politics and a nostalgic view of the Confederacy that was already cause for contestation by some in the 1930s, it endures as a symbol of Old Hollywood craftsmanship at its peak. Indeed, it's difficult to think of a production that better exemplifies the sheer ambition of the studio system, its grandeur, and stunning spectacle. Technical ingenuity abounds, as does an eye for powerful imagery. It's so beautiful that some of its shots endure as cultural artifacts, even when divorced from their origin.

Today, I want to celebrate one aspect of its splendor near and dear to my heart – the costumes by Walter Plunkett. Specifically, I've given Scarlett O'Hara the same treatment Bella Baxter got, and ranked her ten best looks…

Walter Plunkett started his career as a movie extra in the 1920s, having abandoned his law studies to pursue a life in show business. By 1927, his professional path had moved to behind the camera, as he got his first costume credit for RKO's Hard-Boiled Haggerty. He'd later serve as Head of the studio's Wardrobe Department, rising in prominence as one of the industry's experts in period costuming. That being said, you shouldn't look for historical accuracy in the American movies of this era, as they privileged glamour above any adherence to fact. Whether as an aesthetic or artistic movement, realism wasn't to be found in Plunkett's pictures.

And, honestly, I'm not complaining. Let cinema be a dream factory, a fountain of fantasy that can show us the impossible, worlds that never were and never will be. That didn't stop studios from advertising their travels into the past as authentic, though. That was Plunkett's assertion when talking about Gone with the Wind. He first read the book under Katharine Hepburn's recommendation and grew to love its sprawling narrative. When David O. Selznick started preparing a big screen adaptation, the designer offered his services right away, getting the job primarily because of his work on George Cukor's Little Women.

Unlike most productions, however, this one stretched for years in development. So much so that Plunkett had time to go South and supposedly research extant garments, fashion plates, and testimony from people who were alive during the Civil War. He even had talks with the book's author, Margaret Mitchell, getting her permission to deviate from her sartorial descriptions. If not, Vivien Leigh would have worn little other than green and mourning black throughout the movie. Don't get it wrong, there are still a lot of emerald shades in the final cut, but it's combined with other colors and their symbolic portents.

Despite support from the author and Selznick's assurances, Plunkett was almost usurped, as the producers were unhappy with his sketches for Scarlett's wardrobe. By 1938, there were plans to bring designer Muriel King into the production so she could create Vivien Leigh's wardrobe in contrast to Plunkett's work for the other characters. Thankfully, the first costumer eventually gave the bosses what they wanted, a spectacle that met all their demands – authenticity be damned. What ends up on screen is a negotiation between fact and fantasy, resulting in a skewed vision of the past. It's what 1939 (white) audiences wished their history was. What could be more appropriate for Gone with the Wind?

In total, 5,500 costume pieces were created from scratch for Gone with the Wind. Their construction cost over 150,000 dollars, while their laundry and maintenance came up to 10,000. A troubled production meant not everything reached the near-four hours edit, with some of Vivien Leigh's costumes forgotten on the cutting room floor. Nevertheless, her Scarlett O'Hara models more than twenty individual ensembles, from 1861 ruffles to 1873 pseudo bustles. It's an extensive wardrobe, dripping with narrative significance and flourishes. Picking just ten outfits was a tough task, and my list would probably differ if you asked me another day. For now, here are my picks for Scarlett's finest fits.

10) GILDED GLAMOUR

Though it features in promotional material for Gone with the Wind, this Gilded Age wrapper is barely visible in the film. Vivien Leigh only wears it once, after Scarlett and Rhett Butler's wedded bliss has started souring into something nasty after their daughter's birth. Stylistically, the scene is all about invoking the character's past, making us reflect on how much the protagonist has evolved. Though maybe she hasn't. The tightlacing getup echoes an earlier scene with Hattie McDaniel, though the virginal white of youth has given place to gold. The wrapper itself – a type of clothing meant to be worn in domestic intimacy – is reminiscent of yet another moment in Scarlett's spotted past.

Notice the shade of green velvet and its contrast with yellow gold. You'll see the same combination later on the list, though it'll be for a much less luxurious piece. She once wore curtains when trying to deceive Rhett. She now dons French fashion as his wife. But, even beyond that connection, the green is vital for Scarlett's character. It's the visual cry of her Irish heritage, a source of pride her father instilled in the woman from a young age. From there, it becomes a leitmotiv in Plunkett's designs, associated with greed, envy, capital, and the character's rebellious nature. In other words, green is the color of self-assertion within Gone with the Wind's narrative and Scarlett's conception of her own identity.

09) AN ICONIC END

Scarlett O'Hara starts her screen journey as the picture of Southern prosperity, crinolines exaggerated to proportions they never had in real life. She ends it in a more streamlined silhouette, reminiscent of 1870s bustle gowns, though not especially ostentatious as those garments could be. She starts in white and finishes in black, innocence to maturity and optimism broken into a more pragmatic hopefulness. The bolstering of nostalgia is almost completely gone for her final moments, abandoned and left to consider the cost of lifelong selfishness. Just once she seemed in reach of redemption, punishment fell down from the heavens.

She's in mourning, as she is in many parts of the film. Sometimes, it's in honor of dead husbands she never cared for. On other occasions, black denotes the loss of a daughter or a friend. The way she wears it varies, too, reflecting character change as well as the ways of fashion. Early on, Scarlett is a peacock forced to behave against her will, hiding the bright plumage beneath insincere modesty. Here, however, her sadness is genuine, and the camera renders her outfit like a black hole. Apart from the angular lines of shoulders, high neck, and miniature bustle, no detail survives the void. Well, there's that cameo brooch, which is oversized and in classical style. It denotes wealth but also makes her look like a museum piece, an object created for a time that is no more.

08) WIDOW'S WEEDS AT THE BAZAAR

This style of mourning is much more in line with Scarlett's self-interested character. In a brattish tone, she complains about needing to adhere to the social codes expected of widows. She can't wear color or jewelry, can't go to parties or other social events. And yet, here she is at a charity bazaar in bustling Atlanta, paired with Melanie for company. As sister to Scarlett's dear departed husband, she's also in mourning, providing a good contrast for how Walter Plunkett styles the two characters. They're both in demure black taffeta, which I believe is meant to suggest the crepe textiles preferred for widows in the 19th century.

However, Scarlett can't help but pull focus. As if exaggerating her sorrow, she's even more covered up than the pious Melanie, gloves hiding the wedding ring she proffers to the Confederacy cause following her sister-in-law's similar donation. Then there's that incredible bonnet, tied with a long bow in the front and capped by an even more extravagant veil in the back. The transparencies allow us to see a snood – such hairnets would become popular in the early 40s because of Gone with the Wind – and makes for a flurry of fabric when she dances through the crowd. The contrast between her and the other women is stark, a morbid vision of unrepentant transgression.

07) SOUTACHE AND STUFFED BIRDS

I've poked holes in Plunkett's affirmations of historical accuracy so far, but here's a costume that does owe much to documented fashions. The fit of the bodice is still defined by 1930s tailoring, and the hat is similarly inclined. However, the suit is a fantastic piece taken almost wholesale from fashion plates and period photography. The combination of light blue cloth covered in black soutache is characteristic of the time, and even the acid yellow details can be correlated to the popularization of Aniline dies in the second half of the century. But of course, like every Gone with the Wind costume, there's more to it than superficial accuracy.

The palette suggests Scarlett as a peacock -again!- at a moment when the new Mrs. Kennedy is starting to flaunt her wealth, and the stuffed birds on her chapeau further that impression. She's also a businesswoman, and the costume reflects that by appealing to notions of masculinity. Notice the white starched collar, how it underlines her new status, feeling more akin to a 1930s men's shirt than an 1860s lady of means. That said, the horizontal configuration of the soutache across the bodice links Scarlett to the men of her time. Specifically, it evokes the braiding that decorates military uniforms. Even if the war is over, Scarlett's battles continue.

06) "I'LL NEVER BE HUNGRY AGAIN"

The simplest of Scarlett's costumes is also the one she wears most often. In the middle chapter of Gone with the Wind, Vivien Leigh dons the print cotton piece, starting with early scenes as a nurse in Atlanta to later events set in Tara in the early days of Reconstruction. To be accurate, there are two outfits made from the same fabric - the dress and a simpler bodice with fitted sleeves from armscye to wrist. This one feels more powerful as a design, primarily because of those sad poufs around the shoulder. Without proper filling and upkeep, they look deflated, ghosts of a past frivolity that's now unsustainable. It's visual short-hand.

The skirt also drags, for it was made to be worn over hoops and petticoats. Without them, the hem pools and brushes the dirty ground, fading fast and tattering along the way. As for the color, it gets muddier as the days go by, as if bleached by the sun, tinted by soil. At times, she wears it with a hat reminiscent of the same she took to the Twelve Oaks barbecue – another reminder of a way of life she left behind, lost. Furthermore, there's a matter of character reflections. In its first appearance, the outfit is an accusation. For all her performance of piety, Scarlett is closer to a fallen woman like Belle Watling than the saintly Melanie. Later, it's a sign of destitution by twinning her with Prissy.

05) THE SCARLET WOMAN

Many verdant shades can be found in Scarlett's wardrobe, but there's also a lot of red. If green is the O'Hara's Irish heritage, then ruby is Tara's soil. It's also a sign of sexuality and the breaking of social norms, which can sometimes manifest as a reflection of Scarlett's power. On other occasions, it's a sign of Rhett's outrage at her behavior, his punishment. Such is this case, worn at his behest after Scarlett's been seen embracing the married man she's spent a lifetime coveting. Instructed to wear rouge by her enraged husband, Gone with the Wind's heroine looks the part of the scarlet woman. In other words, I present you slut-shaming in dress form.

While Plunkett's original sketches had a vaguely (and already anachronistic) 1890s sweep to the silhouette, every bit of 19th-century specificity was excised for the final costume. All the better to make her stand out from her surroundings. Against Melanie's more casual clothes and humble abode, Scarlett looks out of place, wholly inappropriate, and aware of it. The tulle wrap encircling her figure, the spangles sparkling red, and the feathers are all reminiscent of another character, though. One that's not even in attendance. Scarlett is an echo of Belle Watling from when we first saw her at the hospital's entrance. She is a fallen woman in high society's eyes.

04) BARBECUE GREEN

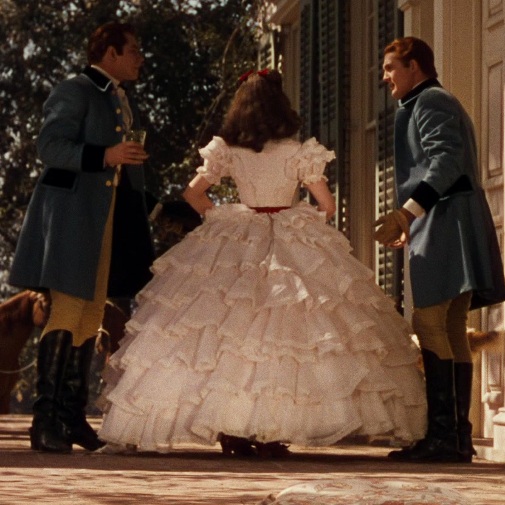

After that little detour into red, let's return to Scarlett's favorite color. To attend a barbecue at Twelve Oaks, the O'Haras' oldest daughter chooses another inappropriate piece, though she's in full control of her image this time around. Fittingly, Plunkett doesn't obey the norms of 1860s dress, where short sleeves and bared shoulders were exclusive to evening attire. His decision to bare so much of his leading lady's skin makes internal sense within the narrative. He contrasts her with women in more demure dresses, including Melanie, covered in yards of Confederate gray. Scarlett intends to be seductive, her dress a provocation.

In dialogue, Mammy complains about the teen girl showing her bosom before three o'clock, trying to fluff the ruffles around the décolletage and shoving the straps up her shoulders. Plunkett's design looks like a deliberate misinterpretation of a Bertha collar, both to facilitate these points of physical comedy and to render Scarlett more stylish to a contemporary viewer. As with most of her short-sleeved costumes, this mousseline number is more akin to a 1930s dress with a hoopskirt shoved underneath than a proper 1860s garment. The sash suggests a modernization of the Swiss belt, and the hat is so wrong that it's right. Halo-like, it frames Vivien Leigh's face and helps her dominate the busy frame when Scarlett arrives at Twelve Oaks. You can't take your eyes off of her.

As said before, the politics of Gone with the Wind are atrocious, extending even past the racial dynamics and Confederate glorification. In this scene, for example, Rhett brutalizes Scarlett after threats of violence. Somehow, the suggestion of marital rape cuts directly to next morning, when a repented husband finds his wife cheerier than ever, as if the violation finally broke through her infatuation with another man. The characters' interior ugliness is one of the film's most fascinating and best aspects, so I won't bother you with more moralization. In formal terms, the entire sequence is a triumph of image-making in its rawest terms.

Much of that concerns the lensing, how Victor Fleming framed the moment in quasi-Gothic opulence, all deep shadows and cavernous architecture. The cinematography enhances the darkness, but it also deepens the bright colors on screen. Bedecked in red velvet, Vivien Leigh is a flame blazing on screen, a red slash opening in frills and bared flesh. The entire costume radiates sex, violence, a show of vulnerability under a dangerous gaze. Even the cut of the skirt is heightened, trailing behind, swallowing so much light it looks like an extension of the shadow. It's as if Scarlett is bleeding into the house, becoming one with its grandeur, for better and worse.

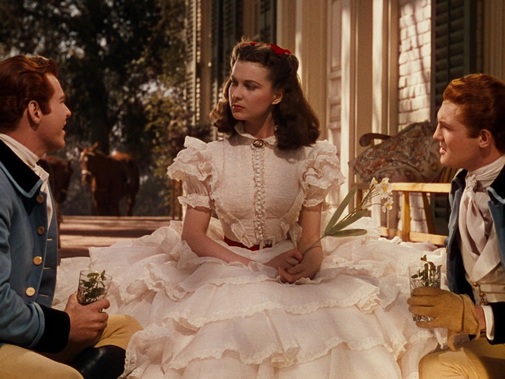

02) AN ICONIC INTRODUCTION

Intentionally or not, Walter Plunkett introduces Scarlett as the picture of white privilege in the Old South, perpetuating an illusory innocence over a foundation of blood. The white fabric layered in ruffles recalls the cotton sustaining the economy, while its arrangement is almost flower-like. Scarlett matches the blooms scattered through Tara, blossoming in the background of scenes. Or maybe she's a confection, some dessert melting in the sun, so sugary it'll rot your teeth with a single bite. Putting on coquettish airs, Vivien Leigh doesn't hide Scarlett's insincerity, projecting that the young woman's innocence is a deception.

Her selfishness will soon come to the forefront of the story, making this costume look all the more grotesque. And yet, it's beautiful and impossible to forget, constructed from a myriad of inspirations to make up an image that's more Hollywood dream than Antebellum South. The bodice is prim and girly, made from lace that recalls early 1900s lingerie dresses. The red belt and pumps contrast the froth, while the bows on Leigh's hair suggest a Shirley Temple doll. You take one look at Scarlett, and you get her character, her contradictions. You instantly understand what she signifies and what she means, both within her narrative and culture as a whole. It's a masterpiece of costume design.

01) CURTAIN COUTURE

How could I choose any other costume for the top spot? It's been parodied from The Carol Burnett Show to RuPaul's Drag Race, an icon of silver screen scrappiness and the peak of Scarlett's resourcefulness as a desperate woman willing to do anything to survive. Once again, it's green, with the ties to the O'Hara's erstwhile fortune literalized in its textile. Scarlett is literally wearing a piece of Tara, enshrining herself in its hollow promise to convince Rhett to give her a loan. This is costume as costume rather than costume as clothing. The fakery is the point, and what a glorious sight it makes, arsenic green from top to bottom, with passementerie recycled as fashion trim.

Speaking of fashion, Scarlett's sense of it seems outdated by this point in the story. Crinolines have turned more oval in the late 1860s, even the version of it we see on screen. So, her dated hoops are more ridiculous than ever, so impractical they seem to encumber her every step. The capelet over one shoulder is cute, but it's also another flourish too many, heightening the piece's theatricality until anyone can see through the smokescreen of magnolia perfume. Still, if made to choose my favorite part of this getup, I'd have to go with the hat. Its asymmetry is an elegant anchronism, with the rooster feathers and feet making for a macabre accessory.

Serving "Project Runway unconventional material" realness, Scarlett O'Hara consolidates her status as a fashion icon for the ages. All hail, Walter Plunkett!

Though I recommend watching Gone with the Wind on the big screen if you can, the picture is streaming on Max and TCM.