This past weekend, Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation celebrated its 50th anniversary. Originally released in 1974, the film represents the peak of the paranoia thriller craze of that decade, encapsulating a cultural zeitgeist along with the creative zeal of New Hollywood. And yet, it's usually overshadowed by the director's other release that year – Best Picture winner The Godfather Part II. Thankfully, at The Film Experience, we've regularly showered praise on The Conversation, whether in Cannes at Home musings or Hit Me With Your Best Shot analysis. That said, one element remains under-discussed, a facet of this masterpiece so essential that, without it, the entire project would fall apart. It's Gene Hackman, of course…

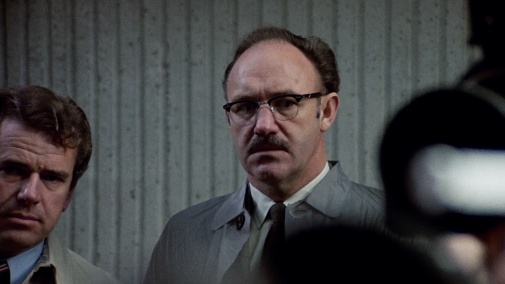

The opening to The Conversation is nothing short of miraculous, fusing form and narrative to convey a surveillance apparatus like nothing else in cinema before or since. The setting is Union Square in San Francisco, while the subject is more difficult to parse. Using telescopic lenses and a conspicuously unreliable sound mix, Coppola has the viewer contemplate the scene from afar, slowly zooming into it in search of some figure that's more than a mere extra. Though the hushed words of a man and a woman soon reach the spectator's ears, their eyes are guided toward a man in plain clothes and a raglan raincoat. We first see him as a nobody, anonymized by the overhead framing and significant distance from the camera.

He's Harry Caul, a wiretapping expert hired to record the conversation between that couple. Played by Gene Hackman, his movements through the Square seem casual at first, gaining a more suspicious quality as one realizes the purpose behind his loitering. The casualness is a deceit, for there's nothing incidental about how he walks from vantage point to vantage point, mingling with the crowd. Only his eyes keep slipping toward his targets, sometimes more openly than what we'd expect from a precautious professional. In fact, the first time we can adequately see the actor's face, an unreadable look comes across as he steps into reaching distance of his marks.

Is it curiosity? Maybe it's a flash of sudden empathy within the dehumanizing toll of his labor. The Conversation seldom delivers closed conclusions to psychological inquiries, but Hackman's performance provides enough clues into Harry's interiority. The actor is essentially playing someone who's turned himself, by choice and profession, into a non-person. By the time we meet him, Mr. Caul is a passive entity that observes and records, spying for the highest bidder while telling himself that what happens after the job has nothing to do with him. Of course, that's an untruth, and he knows it. You can see the realization long before the text spells it out.

Hackman's general approach is a curious turn for the same thespian who had recently won an Oscar for a radically different character in The French Connection. Most of that movie's overt aggression is gone here, substituted by the general air of someone who's given up on life or is striding in that direction. There's still an inkling of bullishness, though. Consider our first glimpse into Haul's apartment, when, upon finding a birthday gift, he becomes fixated on finding out how his neighbor got into the home. Talking over the phone, Hackman lets his body decompress, with Harry undressing for a relaxing time at home. However, as his physicality becomes more and more open, the vexation rises.

When the chatter comes to a close, it's pretty obvious how much this violation has shaken Harry, and how much he detests the thought of someone stepping one foot into his space without him knowing. With little more than a slight change of tone and the unbuttoning of his pants, Hackman lets us know much about how Harry moves through the world, engages his surroundings, and separates himself (or doesn't) from his job. A man is his vocation, so Harry is a master of secrets. That's as much of a blessing as a curse, of course. For example, he's nervous all the time, even when doing things that are part and parcel of the job, like fixing meetings to deliver tapes and receive payment.

On the personal side, Harry's secrecy has rendered him closed off to the point of isolation. Shortly after the Union Square business, we get to see that in detail as he visits an old fling for whom his secrecy is too much to bear. With Teri Garr, Hackman embodies the reality of loneliness like a corrosive thing. It's also a barrier that sheaths Caul's whole being. He can't seem to pass through it, even if his eyes shine with the need to connect. That vulnerability in the actor's gaze paired with a stony expression, a fixed frowning mouth, make for a powerful image. We can learn much about Harry Caul just by surveilling the slight variations of his face. And there's his body, too, his gait and posture.

Perpetually alert and self-conscious, Harry Caul walks like a man who's always considering how he's being perceived by those around him. That latter detail becomes interesting when you compare his comfort in the shadow to the disquiet that seems to overcome him in the light. Wandering into the public offices of his client, the Director, he finds himself in an environment that's way too open for his liking. You can see it in the way he's all abortive gestures, as if he doesn't know how to arrange his limbs or maybe wants to shrink himself invisible. The portentous warnings of Mr. Stett, the Director's assistant, destabilize him further.

By the time he's leaving through an overcrowded elevator, Caul is shaken to the core despite maintaining a veneer of normalcy. From this moment onward, guilt perspires from his every pore, the shadow of his eyes graying from lonesomeness to a haunting. What will the Director do with the recordings when he gets them? What will happen to the woman in Union Square? At his workshop, a colleague's invocation of the Lord's name in vain suddenly brings another factor into our understanding. Harry Caul is a religious man, Catholic to be precise, with all the guilt that comes with it. And just like that, his obsessive finagling with the tapes gains another dimension, a spiritual toll weighing down on his conscience.

When he isolates the words, "he'd kill us if he got the chance," the scene is set for the ruination of whatever's left of him. But wait, there's a convention to attend, some meaningless socializing with old partners in crime and envious rivals. There, he runs into Mr. Steet again, and it's like an electric tap runs through him, a burn that begets agitation. Perchance to calm his nerves, Harry drinks, and Hackman delivers a masterclass in tracing a long night's journey from a pleasant buzz to dangerous candidness. Technique-wise, it's all about performing the struggle to maintain focus rather than projecting intoxication. Tonally, it's about walking the fine line between comedy and tragedy.

Back in his workspace with a cadre of companions in tow, he recounts past jobs with newfound cheeriness, flushed with pride and booze. But it all goes to shit when a colleague recalls the time Harry's recordings resulted in three murders. The guilt that's been slowly fermenting for an hour finally bubbles over. It first strikes angrily but then hides like a frightened animal. When he gets the chance to boast about his engineered solutions, Harry goes all in, overperforming his gloating and sense of superiority toward the other men. But then he discovers he's been spied upon, and the humiliation falls back into fury, uglier than ever. It's an incredible piece of acting, moving from mood to mood, gradating responses to sing the rhapsody of a man's interiority.

Through it all, there's a second song playing in parallel, as Harry opens himself up to a woman's prying affections. Interacting with Elizabeth MacRae's Meredith, he seems dejected, as if forcing himself to participate in the seduction. It's not that he looks suspicious of her – no more than he is suspicious of every person who crosses his path – but that another woman's fate troubles his mind. He's distracted beyond eroticism but not beyond intimacy. In a moment of weakness, Hackman's Harry is more revealing than ever, the timbre of speech wavering in the threshold of a subtle sob. And in the end, his lack of caution comes to bite him in the ass. Meredith purloins the tapes, and Mr. Stett promptly calls Caul to inform him they have been delivered.

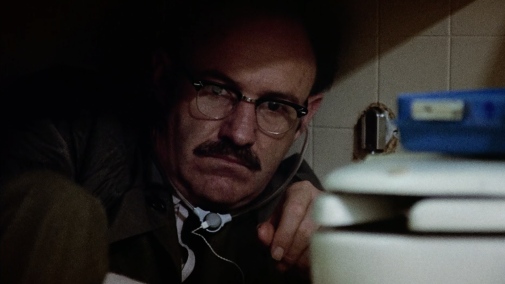

Paid in full and told to forget everything, our protagonist can't let go of his fears, confident that a murder will take place. So, he throws caution to the wind and books a hotel room adjacent to another mentioned in the original conversation. There, he waits and listens. Watching him at work, finding any way possible to overhear what's happening in the adjoining suite, is a study in meticulousness on the verge of obsession. Yet, Hackman doesn't over-emphasize his actions, honing on the ways Harry Caul is used to such business. One gets the sense he's done such things many times before, to the point his hands move automatically, guided by muscle memory.

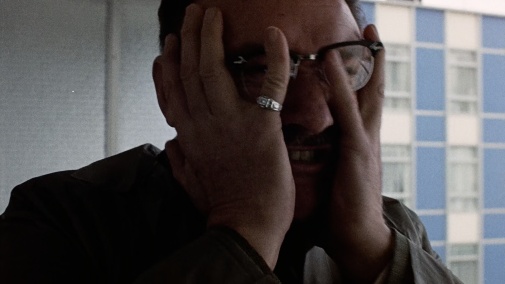

It's essential to consider his cool efficiency even while fear for others' safety overwhelms his whole being. Later on, a similar sequence finds him dismantling his place in search of wiretapping, consumed by despair over his own security. Then, finesse will rot into something much less slightly, much sweatier. But before such conclusions, there's a shock of violence next door, obscured by the framing but realized in Hackman's discombobulation. His balance goes out, his hands move up in a silent parody of Munch's Scream. Still, nothing compares to the prickling fear that overcomes Harry's visage when he understands what happened.

When he realizes they're tapping him, Hackman communicates the character's visceral response like a bucket of ice-cold water poured over his head. You get sympathetic chills just from watching him panic. At the end of this journey, when there's nothing else to do but blare music into the night sky and call it a day. Harry Caul is 1970s paranoia materialized, alone yet overheard, playing his sax into the night while the world lies destroyed around him. These notions come from Coppola, articulated through his writing and image-making, but they also derive from Hackman's stellar work. It's impossible to imagine the miracle of The Conversation without him.

After winning the Palme d'Or at Cannes, The Conversation went on to earn a slew of other awards and honors. Though most of those centered on Francis Ford Coppola, Gene Hackman scored his share of trophies. He was nominated by BAFTA and the Golden Globes, won NBR, and was a runner-up at the NYFCC awards. Sadly, AMPAS looked the other way, with The Conversation getting only three citations for Picture, Writing, and Sound. The Oscar nominees for Best Actor were Art Carney in Harry and Tonto, Albert Finney in Murder on the Orient Express, Dustin Hoffman in Lenny, Jack Nicholson in Chinatown, and Al Pacino in The Godfather Part II. Carney was the winner that year, while Hackman would return to the Oscar conversation with Mississippi Burning. He won his second and last Academy Award for Unforgiven, as 1992's Best Supporting Actor.

The Conversation is streaming on Pluto TV and Showtime. You can also rent and buy it on Apple TV, Amazon, Google Play, YouTube, VUDU, and the Microsoft Store.