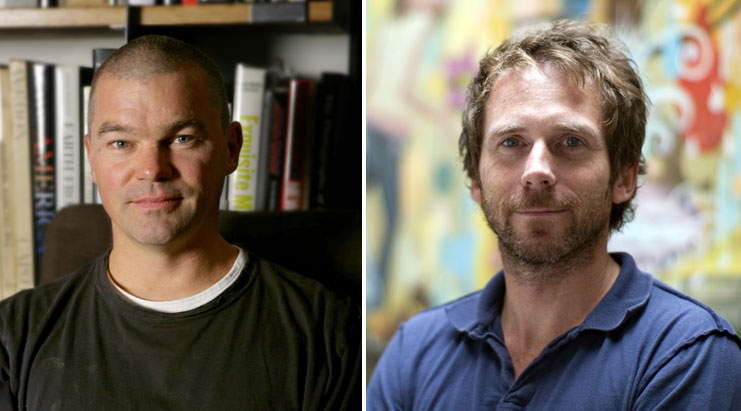

Meet Angus Wall and Kirk Baxter of The Social Network. They were my own gold medalists this year for Best Editing and they're Oscar nominated together for the second time for David Fincher's riveting classic. You won't know their faces but they've contributed significantly to major moviegoing pleasures in the last few years: their assembly skills kept all the difficult pieces of Zodiac's mosaic rubbing together; their attention to detail augmented those complex setpieces in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button; their sense of rhythm and performance shaping kept The Social Network racing along without running roughshod over its dramatic soul. In short, they're quite a gifted team.

Left: Angus Wall. Right: Kirk Baxter

Left: Angus Wall. Right: Kirk Baxter

Herewith some highlights from our conversation.

When I spoke with them last week, they were on a wee break from working on the day's footage for The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo.

Nathaniel: David Fincher has been shooting The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo during the awards season madness. How is this even possible? It must be exhausting.

Have you had any time to enjoy the accolades yourself or does Fincher keep you both locked up in the editing bay?

KIRK: 100%, yeah. There's little opportunity to do back-slapping and champagne drinking. Which is probably healthy.

Both men had nothing but admiration and love for their boss, continually stressing his generosity and loyalty. He gave both men their first cutting opportunity with features. Angus, who has known Fincher for twenty-three years got started as an editor by cutting commercials for him and consulted on Fight Club. Kirk joined the team later with Zodiac. "He likes to pick the apple from the tree," Kirk says.

"He does really well with people who are first-timers, " Angus adds, underlining the point. "He's so strong at knowing what everyone's job is. You get very spoiled by him. He's very clear, very specific and he clears the decks for you to do your job. It's complex work but the task at hand is simple: cut the movie."

Easier said than done of course.

For every scene, hundreds of choices.

For every scene, hundreds of choices.

Kirk calls the work "all consuming", the first thing you think of when you wake up and the last thing you think of before your fall asleep. Fincher is famously known for shooting a lot of footage and the movies aren't the simplest of entertainments.

Nathaniel: Your job just sounds so overwhelming.

ANGUS: David always equates it with how do you eat a whale? One bite at a time.

KIRK: We spend 90% of our time focused on the detail in front of our noses. Only occasionally do we lean back and go 'What's the big picture here?' You have an idea of where you're supposed to head but you just try not to concentrate on how overwhelming it can be and also on the expectations. You get under an illusion that you're making a movie for yourself which is reallly healthy.

ANGUS: it's like running a ultra marathon, there's no racing through it. You've got to plod your way. You just have to do the work and that's kind of the joy of it as well. At the end you see the fruits of your labors.

Angus gets involved first, working out technological details of what's to come with Fincher but the main thrust of their job begins as soon as the first dailies come in. Behind for them, Kirk reveals, is if they haven't done three scenes. They're racing along with the shooting to assemble the rough cut. Despite the intensity of the work, they're eager to go each time. "Honestly," Angus says demonstrating the loyalty Fincher inspires, "When David calls you to do a movie , it's not "what's the script?" It's "OK!"

And off they go.

I wonder aloud if editing, which is often called "the invisible art" is a bit like sculpture. You're chipping away at a huge featureless stone block and eventually you'll see a complicated three dimensional figure. The editors tell me that it's not dissimilar but Angus likens it more like pointillism. "You're not thinking about the big picture but that each color and drop of paint is right for that place and then you zoom out and look at the movie and go 'Oh yeah' or 'Oh no!'"

They work in details right from the beginning. So I have to ask them about one in particular...

Nathaniel: I have to know about that little dance that Andrew Garfield does at Caribbean night. It's so authentic and funny. Was it improv'ed or did he do it in every take?

ANGUS: He didn't do it in every take. It's funny because that's the longest take there is of that pan over. And it's sort of -- when we were cutting it it was excruciatingly long and Ren, who is the sound designer, edited the music to fill that and make his goofy little dance make sense.

KIRK: He's so good at that, Ren. I remember the same thing happening on Benjamin Button with Brad Pitt. He was wandering back with a cup of tea to sit with Tilda Swinton and the way that we cut the scene we couldn't -- we're always trying to make things efficient and as he's doing this slow wander back we were going 'oh god ahhhh it's taking forever.' And then Ren eventually put in this fabulous kind of heater noise [makes thumping furnace noise] and it's terrific. Ren's always going 'Give me those moments!' because he loves them, he gets to dance. We're always trying to eradicate them.

Ren's name appears often in conversation, as a key figure in making scenes really sing. He's also Oscar nominated this year for his Sound Mixing. And once we've moved to the sound another of the movie's laudable achievements, we come around to scoring. Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross's unique score recently won the Golden Globe and adds so much to the picture. But scores are generally completed after the films. How do they edit so successfully before they have it?

Nathaniel: The score is amazing and it affects the rhythm of the film so much, the pacing. How soon did you get it? It feels so fused with your editing rhythms.

Nathaniel: The score is amazing and it affects the rhythm of the film so much, the pacing. How soon did you get it? It feels so fused with your editing rhythms.

ANGUS: About halfway through cutting David brought in "Ghost 1 through 4" which is a set of discs from Nine Inch Nails and he said 'let's try to use this' and i think he'd already started talking to Trent but Trent hadn't said yes to doing it yet. It was unusual because Trent and Atticus Ross did a ton of tracks incredibly quickly in the midst of the edit that we started using which was great. Instead of temp tracks that would get completely swapped out later we had the beginnings of the final score so we were cutting to the blueprint of the final music. Which was just, honestly, it had a pretty profound impact on the film.

KIRK: Huge. It gave us all a lot of momentum and confidence. We started to see the shape of the picture immediately. It started to have one voice.

The opening sequence and the Facemash sequence it kicks off are already legendary. Angus notes that scenes like Facemash which aren't necessarily dialogue driven only really congeal once you have the music. I have to wonder how they ever kept up the propulsive energy of that opening sequence, which is such a tough act to follow yet the film never lags after it. The script was 160 pages, which is quite long for a script, and knowing they needed a movie under two hours, they were continually trying to tighten it. They tightened it so much that the rough assembly was shorter than the finished version which is very rare.

ANGUS: We opened it up a little bit, blew some air or some time into certain moments that needed to land more dramatically. And then we realized we had opened it up too much and we tightened it back up but not to the first assembly. That's the film that it is now.

ANGUS: We opened it up a little bit, blew some air or some time into certain moments that needed to land more dramatically. And then we realized we had opened it up too much and we tightened it back up but not to the first assembly. That's the film that it is now.

KIRK: The way the script is and the way the performances are captured -- the pace wasn't much of a choice. The pace was really dictated by the performances.

You can start to get quite languid when there's no dialogue or with lead-in to scenes. During your assembly you can perhaps give too much respect to introductory shots. Only once you join the scenes together do you sort of go 'all right let's get to the meat of it.' But The Social Network is written in such a way that everything was always spilling. You could not get flabby. As soon as you did the movie would go 'WRONG!'.

Nathaniel: I've heard from other editors that comedy is the hardest thing to cut and the movie, even though it's a drama, it's very funny.

KIRK: My fondness memory of making the film is Angus and I looking at each other and saying "It's starting to get funny". That's not to take away from the writing. There were gags in there that were always great. But once it hit the right rhythm more than just the jokes became funny, the behavior and mannerisms became funny.

ANGUS: That didn't happen until just the very end.

KIRK: That was even after the first screening at the studio.

ANGUS: I think David's movies are sort of about the joy in all the details, the collection of details that make his movies so great.

That word again: details. It arises so much in conversation that I have to wonder if OCD is a requirement for editors. "I don't think you have to have it," Angus says laughing, "but it definitely helps."

Given that these talented men are so often verbally crediting others: the witty screenplay, inspirational strokes in the sound mix, Fincher's general genius and the strong cast, I begin to wonder if they haven't any ego at all to go along with their obvious talent.

KIRK: Angus once said to me 'You don't become an editor to seek attention. Our role is a quiet role. It's really an enjoyable job until you have to start describing it.

And with that there was laughter from all sides. Describing this 'Invisible Art' is just what I'd been asking them to do.

They may not seek attention, locked up in their editing bay weighing the day's footage from an entirely different film, but with their second Oscar nomination, the attention has come to them anyway. Perhaps they'll have to do a little more talking about their "quiet roles" on Oscar night.