[Editor's Note: Beau McCoy is a longtime reader who I met recently. I quite like his writing and have asked him to contribute to the site. I hope you'll encourage him in the comments to return again. He doesn't have a blog so I'm featuring his "Hit Me With Your Best Shot" entry here as a kind of sneak peak to Wednesday night's group activity looking at "The Exorcist". I'm already terrified to follow this entry up. It's quite an opening scene. Are you joining us on Wednesday? -Nathaniel]

[Editor's Note: Beau McCoy is a longtime reader who I met recently. I quite like his writing and have asked him to contribute to the site. I hope you'll encourage him in the comments to return again. He doesn't have a blog so I'm featuring his "Hit Me With Your Best Shot" entry here as a kind of sneak peak to Wednesday night's group activity looking at "The Exorcist". I'm already terrified to follow this entry up. It's quite an opening scene. Are you joining us on Wednesday? -Nathaniel]

by Beau McCoy

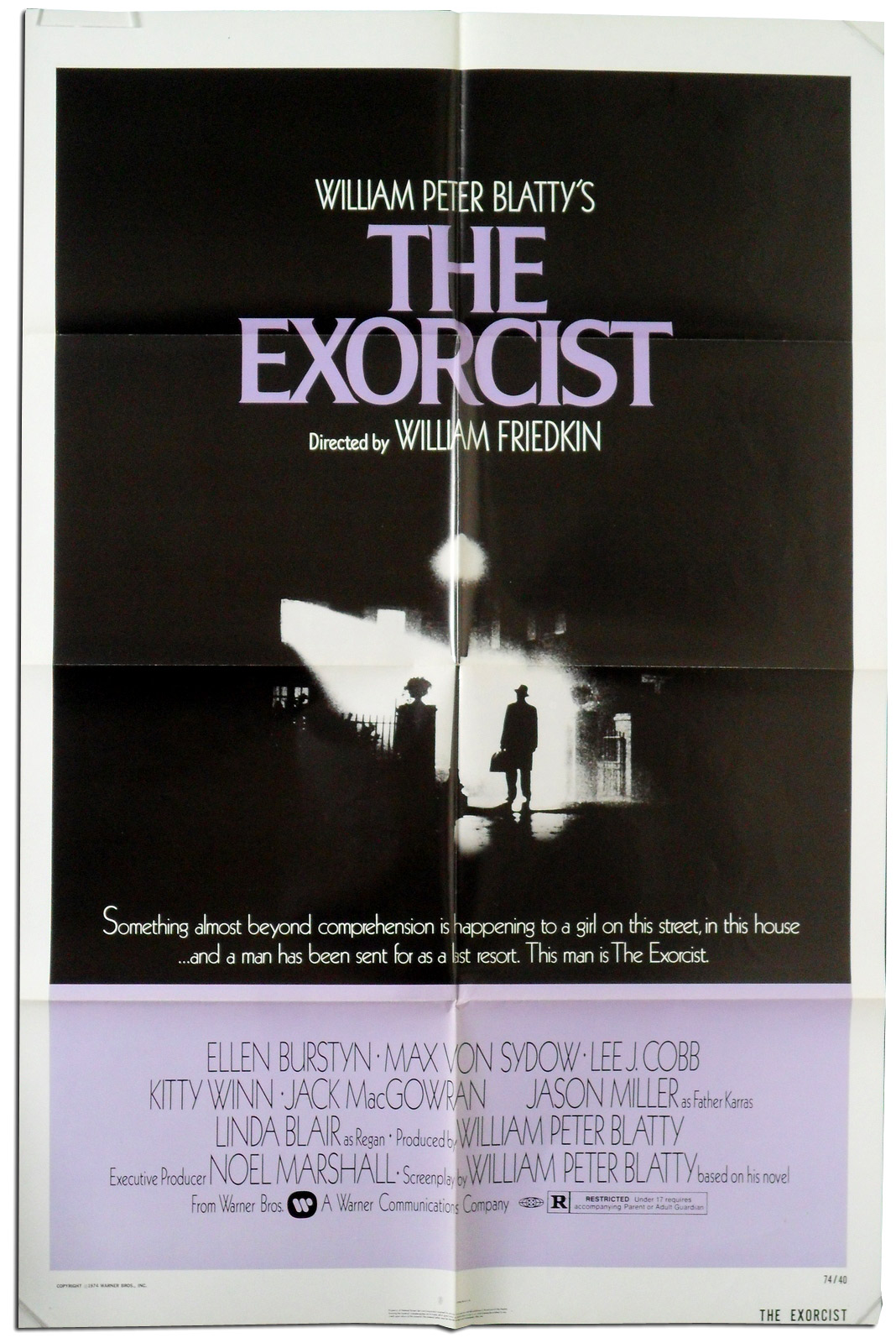

There are few horror films whose reputation precedes them quite like The Exorcist (1973). Even if you never see the film, you know it. You know what it's about. You know specific scenes and you know certain images, even if you can't quite remember how you came across them. In much the same way Friedkin intended for certain subliminal imagery to make its way into the film, (using failed makeup tests with a model), the film inserts itself, impermissibly, into the subconscious of those who experience it in one way or another.

When you hear about films, if you're anything like me, there's something that hits you that I've called 'The Wave'. A tsunami of emotion, memory, nostalgia, fear, and regret that gives you opportunity to view yourself viewing that film in a different time. I can't remember much from the early part of my life. There are people who I see after years and I can't recall exactly how it was I knew or met them in the first place. But with a film, it's as though it made its way into me, burrowing itself into my subconscious, or heart, dick, what have you, and when it's called upon, it pops up cheerfully like an old friend to say 'Hey! What have you been up to?'

The Exorcist, appropriately enough, is not so cheerful. It looms. [Beau's best shot after the jump]

When I returned to the picture this past Tuesday at the Arclight Cinemas in Hollywood, I found certain images and phrases creeping their way out, diverting me from the narrative to a parallel journey alongside it. Where the film could play, and I could revel in what an experience this must be. Roger Ebert notably (and positively) referred to The Exorcist as 'a frontal assault. In keeping with that idea, and in trying to determine what 'best' means for me in this specific context (as it changes with each picture) I decided to search for what particular frame 'assaulted' me in the days following: bullying me, taunting me, egging me on - pervasively making its way into my daily life.

There were many. Von Sydow standing atop a grade facing off against a foul gargoyle (Ebert also mentioned how this felt like an appropriate extension of Antonius Block's battle against Death), the aforementioned subliminal shot of an unnamed demon, Burstyn's relatable fear in so many scenes, but ultimately, I wanted the one that elicited the most fear, the most caution, the one most foreign and alien to my senses as a moviegoer.

And while The Exorcist is certainly sensationalist in nature, and anything with Linda Blair seems all too easy and cliched a choice, it wasn't the sight of pea soup or a bloody crucifix or 'Help Me' imprinted on a adolescent's stomach that haunted me, but rather, this:

It is the one image from the picture that I cannot shake, because everything that I have seen before, be it shocking or mundane, has been an image that I could place in a given reality. Our given reality. The Exorcist, while many things, is not a fantasy. It does not hold our hand during and tell us 'Not to worry, this exists somewhere else, but not here; not with you. You're safe.' If it did, the film wouldn't have elicited such a strong reaction from filmgoers and critics alike (and continue to do so for nearly forty years). The strength of the picture is that it confronts our idea of reality and extends it to the very brink, where whatever hold we have on it breaks, and that innate juvenile fear of the unknown rears itself, and we recoil back into our cushions, our refreshments, our loved ones, because now they are the only anchors we have left. There is nothing else. That is the true essence of brilliant horror; how strongly fear can emanate from a loss of something.

This image is the brink. We have seen fantastical things, yes, but they are captured seemingly without effort, so fully realized by the creative team involved that we never doubt their authenticity for a second. In this image, though, there is nothing to comfort us. No familiar faces or backdrops. Regan's room lost its warmth a while back in the picture, and all it is now is the chosen venue for a battle we don't know how to fight. The warriors don't have any weapons except their own faith (or lack thereof). Nothing tangible to hold on to. No anchors. And here, in the midst of battle, they fall to the ground and look up to see something wholly demonic. Grotesque and amorphous, hardly classifiable as anything but an abject notion cum to the edge of the screen to yell out 'Boo!', and retract back into the celluloid.

Regan isn't here.

Father Merrin isn't here.

Father Karras isn't here.

Antonius Block isn't here.

Linda Blair isn't here.

Blatty isn't here.

William Friedkin isn't even here.

You could go so far as to say Captain Howdy itself isn't even here.

In this shot, as we make our way to the final stretch of our experience with these characters, we see what could have only been thought up in the dark recesses of a dark house, alone, a cigar and a brandy nearby, silence permeating everything, the antithesis of a glimpse of God, or even the devil. It's a glimpse of nothing.

The earmark of horror. How it remains effective.

Because what The Exorcist does so effectively, what truly makes it a masterpiece, aside from all that sensationalism and its reputation, is that it knows itself. And it knows that anything that can exist without reason, is borne from nothing. And to see nothing in its purest form, is enough to question the grasp you have on your reality. So that now, when you walk home from the theater or a friend's house or a bar one night, you look for nothing. And you find it.