Tim Brayton will be looking at several of the contenders for Oscar's Animated Feature race. He previously reviewedThe Wind Rises, Ernest & Celestine, Frozen, and Letter to Momo. This week: Rio 2096: A Story of Love and Fury.

Tim Brayton will be looking at several of the contenders for Oscar's Animated Feature race. He previously reviewedThe Wind Rises, Ernest & Celestine, Frozen, and Letter to Momo. This week: Rio 2096: A Story of Love and Fury.

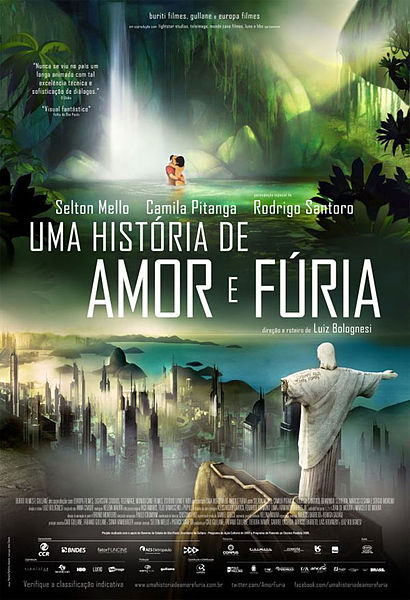

At times, one is reminded to despair for the English language. We have before us a certain Rio 2096: A Story of Love and Fury, named in the original Portuguese Uma História de Amor e Fúria, a superior title on two levels. One is that the “Rio 2096” business is an inelegant distraction. The other and more important thing is that in almost every Romantic language, the words for “story” and “history” are the same, and plenty of writers have gotten mileage out of that fact through the years. At any rate, describing Rio 2096 as something that’s both story and history at the same time is merely accurate. Whereas describing it as something that takes place in Rio de Janeiro in 2096 is accurate-ish, though it reeks of marketing to an audience that remembers when “adult animation” and “used-up future” were basically synonymous, back in the 1990s.

The framework takes place in Rio, 2096, though, so that counts for something. In this glossy, high-tech wasteland, where clean drinking water is the world’s most precious resourced, an ageless 600-year-old man (voiced by Selton Mello) sits grousing about his fate. It seems that his fate is linked to that of the woman he knew in the early 16th Century, constantly reincarnated and always by the name Janaína (Camila Pitanga). It was when the two of them were young, carefree lovers that the young man – named Abeguar at this time – was apparently selected by the god Munhã to be the Chosen One to resist the forces of dictatorial tyranny, in the form of the Portuguese invaders slaughtering the natives of what would eventually be called Brazil.

For those keeping track, that gives us both a Chosen One and an Idealized Woman, and I do not suppose I’m alone in saying that both of those tropes have long since passed their freshness date. The nice thing to say would be that Rio 2096 finds something bold and rejuvenating to do with those stock types, but that’s not the case at all: whatever strengths the film has (and it has some distinct strengths, at that), it has them despite its romantic plot, not because of it (frankly, it plays like a reductive version of The Fountain). At least writer-director Luiz Bolognesi doesn’t appear to be laboring under the belief that he’s telling some kind of remarkably exciting story, and that whole “undying love” angle is more of pretext to justify its time-hopping hero (he turns into a bird whenever he “dies” and is cursed to fly around till a new incarnation of Janaína is available) than the actual bones of the film.

For, if all describes the “story of love” element of the film, the “history of fury” lies in the four specific time periods that Bolognesi chooses to deposit his hero in. Rio 2096 is, primarily, a document of the Brazilian government’s history of crimes against its own people: the indigenous tribes that were cleared out before Brazil came into existence, the African-descended slaves of the 1840s, poor people generally during the military dictatorship of the 1970s. “Fury” is just about the perfect word to describe the attitude the film takes to all this: it’s a vibrantly angry takedown of the violent and oppressive regimes that crop up all through human history, and a remarkably unsparing attack on one particular nation’s history. Most countries in the New World could have a historical drama centered on the theme “this nation’s very existence is predicated on crimes against humanity”, but very few of those movies actually exist.

There’s something electrifying about that kind of rage, if ultimately suffocating. To pair with the savage directness of the scenario, Bolognesi and his animation team employ an equally stripped-down aesthetic that’s superficially akin to anime. But only superficially: the lines are much sharper and more angular than that, and the animation itself (as distinguished from just the graphic design) is less fluid, much closer to a motion comic than anything else I can think to name. Obviously, the budget isn’t in place for a Brazilian animated feature to have the polish and technique of something by Disney or one of the big Japanese studios, and there’s a stiffness to Rio 2096 in places that can only be regarded as the limitation of its production. Still, the animators use it to their advantage as much as possible. The low framerate lends to the film something rough and unsubtle (one might say “primitive”, if there weren’t also so much obvious CGI effects animation), and this accentuates the deliberate lack of subtlety elsewhere. This is a film that underscores and capitalizes its concepts of Love and Fury, and the lack of poetry in the animation contributes to its emphasis.

It is, all told, a bit of a peculiar film, imbalanced between its urgent politics and its reedy love story. Nor would I say that it’s great, must-see animation, though its four time periods are interesting enough in the design. It’s a brave and original calling card, though, presenting a perspective you won’t readily find elsewhere with a distinctive, powerful voice. Rio 2096 is half-formed in several key ways, but it’s utterly unlike anything else going right now, and there’s real value to that.

Oscar prospects: Nil. The only outright “animation for adults” feature they’ve ever nominated is Chico & Rita, which was more coherent both narratively and aesthetically, and more conventionally appealing.