Animated Feature Contender: The Wind Rises

Thursday, December 12, 2013 at 8:15PM

Thursday, December 12, 2013 at 8:15PM Tim Brayton will be looking at the key contenders for Oscar's Animated Feature race. He previously reviewed Ernest & Celestine, Frozen, and Letter to Momo. This week: The Wind Rises.

It’s easy enough to expect great, career-capping things of the final film of any important director even when it was largely an accident of timing that it worked out that. And when the director in question has openly announced his retirement with his film still fresh in theaters, that makes it that much more tempting to view it as some kind of Overt Statement. In the case of Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, it’s a bit hard to say what an Overt Statement might actually consist of, but we can get this out of the way and then relax: there’s nothing about this that feels like a grand farewell to an artform. Far from being a summing-up, it’s probably the least characteristic film of the director’s canon, except in one respect: it makes the fascination with flight and objects in motion, a concern in every single movie he’s made (if only in a very small way), the central driving force of its plot.

It’s easy enough to expect great, career-capping things of the final film of any important director even when it was largely an accident of timing that it worked out that. And when the director in question has openly announced his retirement with his film still fresh in theaters, that makes it that much more tempting to view it as some kind of Overt Statement. In the case of Hayao Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises, it’s a bit hard to say what an Overt Statement might actually consist of, but we can get this out of the way and then relax: there’s nothing about this that feels like a grand farewell to an artform. Far from being a summing-up, it’s probably the least characteristic film of the director’s canon, except in one respect: it makes the fascination with flight and objects in motion, a concern in every single movie he’s made (if only in a very small way), the central driving force of its plot.

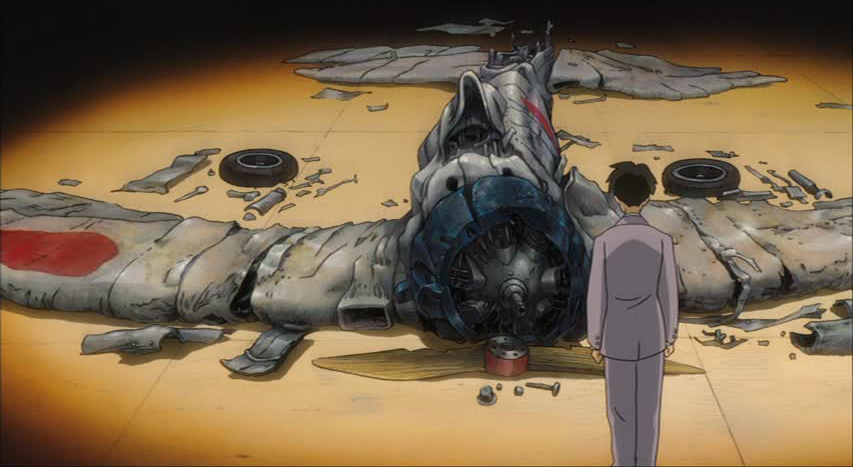

The film is a loose biopic of Jiro Horikoshi (voiced, uncertainly, by Hideaki Anno, director and writer of Neon Genesis Evangelion), the Mitsubishi engineer who designed the A5M fighter plane, and its infamous successor, the A6M “Zero” fighter, the cornerstone of Japan’s airforce during World War II. Miyazaki’s film is almost completely disinterested in the actual matter of the war – near the end it skips straight from 1936 to 1945 – and this has left the film with an unenviable reputation in some quarters as that pretty movie about the pretty planes that makes not the slightest attempt to acknowledge their role in destroying thousands up on thousands of human beings. Which is a hard argument to defend. The entire point of the film is the tension between Jiro’s great desire to build planes, which to him were the most beautiful of all objects crafted by the hand of mankind, and his dim awareness that the only reason he was being invited to build them was to enable his government to kill many people. This is explored with delicate touch, perhaps, but not even too delicate: it crops up explicitly in dialogue throughout, in dreams that Jiro has of the great Italian engineer Caproni showing him ever more impossible and beautiful fantasies of manned flight, cut by the knowledge that humanity will always find a way to make that kind of beauty into a weapon.

But let’s put off that conversation for the moment – I suspect that it’s not going anywhere for the next few months – and attend to the film itself, which finds Miyazaki and the Studio Ghibli animators creating a lovely film of bright colors, lovingly-rendered planes, and almost nothing but quiet moments of humans in reflective repose. This is the first thing that sets The Wind Rises apart from other Miyazaki films, which have all contained at least some kind of fantastic element; the other is the general simplicity of the artwork, which is clean and bright but lacks the outrageous lushness and detail of Spirited Away or Princess Mononoke. Not that imagery of that sort would have any place in such a low-key plot as this. Honestly, even if it isn’t immediately grabby according to the director’s usual standard, I can’t imagine any style that would suit it better than this one.

The story is structured as a surprisingly conventional biopic outside of the intermittent dream sequences. Partially for this reason, it’s also the first Miyazaki film that genuinely challenges the “animation is for children” default setting in the West (which is not at all the case in Japan), telling an adult story from adult perspectives, expressing its anti-war, anti-violence themes with subtlety and implication that even the most sophisticated children’s entertainment would shy away from. Certainly, the central question of the film – is creating great beauty a justification for causing suffering? – is complex and morally ambiguous at a new level even for a filmmaker who has never shied away from a thick moral conundrum to explore.

Still, it’s a largely by-the-books plot, which takes some of the punch out of its undeniable and frequently excellent achievements. Jiro Horikoshi was certainly a fascinating subject with an Oppenheimer-like discomfort for his function in creating new and better killing machines, but his life as presented here has a lot of the usual beats: impressing hostile bosses with his genius, finding the girl that got away years later, only to learn that she has a disease, and so on. By all means, Miyazaki’s treatment of the story is sensitive and effective, and The Wind Rises is always a very involving human story, not a paint-by-numbers hagiography about a Great Man of History. But for a filmmaker whose best work has always been about creating images we’ve never imagined seeing before, it’s a little disappointingly low-key. It’s a fine and moving and exceptionally accomplished work, just not a very special one, and it’s hard not to wish that there was more to Miyazaki’s swan song than that.

Oscar prospects: The brand names involved – Ghibli, Miyazaki, distributor Walt Disney Pictures – make a nomination a virtual certainty. Add in the gravity of the director’s retirement, and this seems like it might even be the frontrunner for the win, give or take the gigantic Frozen box office haul.

Reader Comments (3)

It IS very special. Not just the best animated film I've seen this year, but, maybe the best movie period.

Miyazaki has announced his imminent retirement after his last three films at least. It's almost an expected event at this point. This may very well be the last one for real, but I'll believe it when I see it. The man's like Tezuka, he just can't stop working.

I normally love Tim's reviews, but I feel he's way off on this one. The film is gorgeous from stop to finish and terrifically involving. Far from being low-key, there are terrifying scenes like the 1923 Tokyo earthquake, thrilling flight test sequences including some where the pilots don't survive, and some really sharp editing the flows in and out of dreams with ease and then snaps you back to reality in a new time and place.

But above all, what no American critic seems to realize, this is a straight-up self-portrait. Miyazaki has poured so much of himself and his own story into the movie that it's almost more him than Horikoshi. He grew up with glasses. He was inspired by flight and comics as a young man. He started work at a studio and immediately made an impact with his brilliance, working his way up the ranks. The desk set-up for the engineers at the factory could hardly be more like an animation studio if it tried. He worked harder than anyone else. His friend Honjo looks to me like a close stand in for Isao Takahata--a couple years older than Miyazaki, he advances first, has stronger political convictions and tells him about the world, they challenge each other and influence each other, eventually each becoming project leaders of planes of their own. (Could their boss be a stand-in for Yasuo Otsuka?) Miyazaki is famous for working late and keeping his staff as late as he, though also inspiring them just as Jiro does here. Most of all, he has spoken often of the way his workaholic tendencies short-shrifted his wife, leaving her at home to raise the children while he designed bigger and better films. This is a tribute to his wife, and that "Thank you" at the end is to her.

When you make a film this autobiographical about the process of making art, featuring your favorite theme/image of flight, in your favorite time period (the Showa Period between the wars), giving a final affirmation or love and gratitude to your wife, it kinda sounds like you're making your final film. It absolutely sounds like a "career-capper" and "a summing up."