Amir here, to welcome you back to Team Top Ten, our monthly poll by all of the website’s contributors. For our first episode in 2014, we are looking at The Greatest Working Cinematographers in the (international) film industry. As long time readers of The Film Experience are surely aware, the visual language of cinema is something Nathaniel and the rest of us are very fond of discussing. Films and filmmakers that have a dash of style and understand cinema as a visual medium always get bonus points around these parts. We celebrate great works in cinematography on a weekly basis in Hit Me With Your Best Shot, but it was time to give the people behind the camera their due.

More than 50 cinematographers from all across the world received votes. If the final, somewhat American-centric, list doesn’t quite reflect that, chalk it up to the natural process of consensus voting. Cinematographers like Agnes Godard, Oleg Mutu, Mahmoud Kalari, Rodrigo Prieto and Eric Gautier all had their fans, as did Hollywood stalwarts like Dante Spinotti and Robert Richardson. Furthermore, Harris Savides’s name was attached to several ballots, with the unfortunate note that if he were still alive, he’d be on the list. That would have certainly been the case, so here’s Glenn Dunks with an honorable mention for Savides, and then on to the top ten:

“Does anybody doubt that Harris Savides would appear on this list if it weren’t for his death in 2012 at the age of 55? I would even hazard a guess that he could have been number one. I distinctly remember wanting to know who this man was and what his career had been after witnessing Birth. The way he mixed golden hues of UWS high society with the chilly silver of a New York winter captivated me. That film alone with its graceful tracking shots and magnetic opera sequence would be enough of a game changer if it weren’t also for his prior film-defining work with Gus Van Sant on Elephant, Gerry and Last Days. He would later work with David Fincher (Zodiac), Noah Baumbach (Greenberg) and his last great collaborator, Sofia Coppola (Somewhere and The Bling Ring). A mighty force taken too soon.”

TOP TEN GREATEST WORKING CINEMATOGRAPEHRS

10. Dion Beebe

“Who on Earth is Dion Beebe?” felt like a common question in the early-to-mid-2000s when the Australian cinematographer stormed onto the Hollywood scene. Whatever it was that director Rob Marshall had seen of his prior work that gave him enough faith to turn to him for Chicago I’m not sure – Australian films Praise and Holy Smoke! were hardly indications to hire him for a lavish musical – but beautiful work it was. Still, if his further collaborations with Marshall on Memoirs of a Geisha (for which he won an Oscar) and Nine (for which he should have been nominated) suggests perhaps little more than a handsome craftsman, then it was his sensual and sensorial work on Jane Campion’s In the Cut, visually representing erotic tingles with images, and Michael Mann’s digital masterworks Collateral and Miami Vice that proved he was a bold and innovative one, too. – Glenn Dunks

9. Bradford Young

9. Bradford Young

Bradford Young is still somewhat of a cinephile's secret treasure. The doyenne of the film festival scene, he burst into our consciousness in 2011 with Pariah and Restless City, winning at Sundance for the former, and winning again at Sundance last year, for both Mother of George and Ain't Them Bodies Saints. Young's restrained, poetic style recalls the drained, lucid look of Vilmos Zsigmond's work in the 1970s, with his organic approach favouring natural lighting. Often working close to his own cultural heritage, Young has a keen, youthful but sober eye for evocative, melancholic imagery, finding deep connections between character and place, and capturing an intimacy that still feels observational and diverse. His work feels wise beyond his years but also fresh and tactile; an indelible confluence of precision and instinct. There's surely much more to come from this wunderkind in the years ahead. – David Upton

8. Bruno Delbonnel

There are cinematographers we praise for the subtlety and delicacy and invisibility of their work. Bruno Delbonnel is not one of these people. From the sugar-rush colors of Amélie to the autumnal weariness of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince to the wintry Inside Llewyn Davis, his is a career dominated by bold, unapologetic gestures of color and shadow that tend to feel like some anachronistic blend of German Expressionism and MGM Technicolor. But as obvious and arguably overbearing as his work can be, it’s also almost invariably transporting: prideful eye-candy that willfully sidesteps any kind of realism in its attempt to create emotion from sheer spectacle. That’s what Greenwich Village as a stand-in for Purgatory “ought” to look like, chilly and hard; that’s what a Parisian girl’s fantasy of the wide world “ought” to look like, bright and poppy. Gaudy, perhaps; intoxicating and involving, beyond question. – Tim Brayton

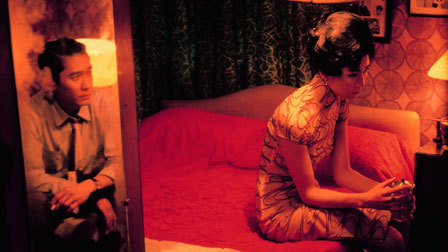

7. Christopher Doyle

Although born and raised in Sydney, Australia, Christopher Doyle's work seems to have come alive within the world of Asian cinema. Having worked with such celebrated directors as Zhang Yimou (Hero) and James Ivory (for the Shanghai-set The White Countess), it is perhaps in his collaborations with director Wong Kar-wai, whom he's worked with on 7 films, that Doyle's artistic vision has truly shone. From the colorful, genre-bending, time-jumping elegance of 2046, to the kinetic frenzy of Chungking Express, Doyle's work is always innovative and alive. But the film that he'll be forever remembered is the lushly romantic slow-motion of In the Mood For Love–a movie so gorgeously filmed that even shots of Mahjong and canisters of noodles are swoon-worthy. Never has unrequited love ever looked so beautiful and sexy, with the camera virtually pulsating with Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung's pent-up desire. In the Mood for Love is one of the greatest love stories ever captured on film and Doyle's work is the (aching) heart of the film. – Andrew Stewart

6. Hoyte van Hoytema

When I think of great cinematographers and Hoytema’s name comes up, my mind tends to go to one particular shot immediately – Benedict Cumberbatch trapped, at least visually, in the labyrinth of the Circus library stealing a file in one of the tensest scenes in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. It might seem to be poor form to so readily zero in on a single scene as representative of Hoytema’s talents because it belies his range as a cinematographer. Still, what makes me remember that moment is not just the specific role it plays in that film but the way it represents my favourite thing about Hoytema’s work: his talent at evoking mood with a few shots. The role camerawork in film plays in informing your mood might seem negligible until you think about how the suffocating colours of Let the Right One In are as responsible for the terror as the story itself. That mood of easy peacefulness which pervades Her has as much to do with the score as the soft hues that Hoytema utilises. That The Fighter manages to remain sanguine amidst the dysfunction of the family has as much to do with the screenplay as with Hotyema. He is a fine example of how cinematography, more than only making things look aesthetically pleasing, plays a significant role in the way we experience films. – Andrew Kendall

5. Robert Elswit

Robert Elswit may very well be the most versatile mainstream cinematographer working in Hollywood today; or, at least, the most accommodating. Elswit’s typical flair with color, contrast, and composition translates elegantly within any number of genres, eras, and locations, complementing dissimilar directorial styles, so that the buzzing, mobile camera that encapsulates the giddy porno wonderland of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights is not exactly the same one that so smoothly captures the stolidly handsome, monochromatic offices and news desks of George Clooney’s Good Night, and Good Luck. Elswit is capable of breathtakingly grandiose cinematic spectacles, from that blazing, Oscar-winning oil derrick in There Will Be Blood to Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol’s death-defying wall-climb up the side of the Burj. And he is gloriously adept at finding a visual specificity within the foreign locales of globe-trotting potboilers, whether they be a bonkers Angelina Jolie spy vehicle or a substandard Bourne movie. Still, I’m just as awed by the ground-level work as well: the perfect, colorized balance between the real and hyper-real within Magnolia’s frenzied human fantasia; the taut, tight frames of Michael Clayton; the spooky, modern-day pulpiness of The Town’s lensing; and Duplicity’s slinky, jazzy photography. No matter the director, no matter the vehicle, Robert Elswit thankfully remains the old pro we can rely on. – Matthew Eng

4. Seamus McGarvey

Does it mean anything that Seamus McGarvey seems to have no specific McGarvian calling card as a cinematographer? A cinematographer is not a director, so the ability of the DP to be an auteur seems scant; still, I’ve heard so many criticisms of McGarvey’s unremarkable, somewhat utilitarian, style it makes me think. Utilitarian may seem an unusual adjective for the man having so much fun with style in Anna Karenina but even as McGarvey shoots films beautifully when it fits, his own potential for peculiar personal aspects depends on functionality within the film he's working on. As it should be, really. The McGarvey framing the gorgeousness of Anna and Vronsky’s passion is not the same who frames the banalities of Lennon’s teen-angst, or Eva’s masochistic suffering, or Briony’s skewed perspective. And none of those is the McGarvey telegraphing the arresting psychological sombreness of The Hours – my first introduction to him. As trite as it sounds, McGarvey gets people, understands how these different characters in varying times demand to be shot in different ways. If he has a calling card all the way from the dying teacher in Wit to the band of superheroes in The Avengers it’s the way he telegraphs so much just by the way he decides to frame his characters. If I were to choose a McGarvey shot as favourite from any random film, it would likely be a shot of a character's person or face than a shot of the mise en scène. – Andrew Kendall

3. Greig Fraser

My relationship with Greig Fraser started when I saw Bright Star at a decrepit indie theatre where the walls were adorned by cracks in the concrete and loose pebbles. I imagined this is what Alcatraz’s movie nights must look like. The theater owner told my friends and I that the film was shot so beautifully that one could take a picture of any shot and frame it on your wall. Not even a minute into the film, and I understood exactly what he meant. The precise way Greig Fraser captures these moments of visual splendor, the internal happiness of the characters directly represented by the gorgeous shots, is nothing short of extraordinary. I might never lie in a field that serene, contort my way through tree branches, or even relax in a bedroom with a billowing curtain so magnificent. But, Fraser has given my laptop background the next best thing. – Adam Armstrong

2. Roger Deakins

I could probably make a pretty airtight case that Roger Deakins deserves the top spot on this list without resorting to waxing poetic about the power of his imagery. From his groundbreaking use of digital color correction on O Brother, Where Art Thou? to the way he is bringing the full texture of live action cinematography to the world of animation in films like WALL-E and Rango, the scope and influence of his career is undeniable. But Roger Deakins doesn’t occupy the top spot on my ballot for such practical reasons. He occupies it because of the visceral emotional connection he engenders for the films he shoots. Deakins never fails to locate images that act as a visual summation of the entire film. Think Jesse James silhouetted against an oncoming train or the camera floating into the sky above Shawshank prison as Mozart plays. Think William H. Macy schlepping through a parking lot to his frozen car, a tiny dot on a sea of blank white snow. More than any other cinematographer Deakins is able to craft images which lodge themselves permanently in the viewers consciousness. – Michael Cusumano

1. Emmanuel Lubezki

Lubezki quickly distinguished himself for achieving rich atmospherics, enriching great vehicles (the lush textures and striking light sources of A Little Princess) or elevating dubious ones (the lambent fogs of Sleepy Hollow, the romantic resplendence of A Walk in the Clouds). Even gratuitous gestures, like that across-the-water aerial intro to an interior dolly that opens The Birdcage, augured brilliant things in the future. Mind-bending, eye-popping sequence shots have become a trademark, in circumstances as different as the misty, smoky practical locations of Children of Men and the overwhelmingly fabricated, airlessly sleek environments of Gravity. This flexibility, in fact, might be his most astonishing gift, from the ecstatic mobility and marionetted sunlight of his lensing for Malick to the lugubrious Gothic pastiche of Lemony Snicket to the 70s grunginess and character detail of The Assassination of Richard Nixon to the world’s most visually dynamic road trip in Y tu mamá también. – Nick Davis

Previously on Team Top Ten

Directors of the 21st Century | Oscar’s Best Actress Losers | Comic Book Adaptations | Women For Honorary Oscar | Awards Season Flops | Horror Films (Pre-Exorcist) | Horror Films (Post Exorcist) | Oscar’s Best Actor Losers