Manuel is working his way through all the LGBT-themed HBO productions.

Last week we went a bit #NSFW and looked at six gay sex scenes that ranged from violent/sexy (Oz) to just fully sexy (Looking). This week, we go from the sexually explicit to the (homo)sexually implicit as we turn to The Celluloid Closet and the HBO documentary Vito (Netflix) on the iconic queer film historian, Vito Russo.

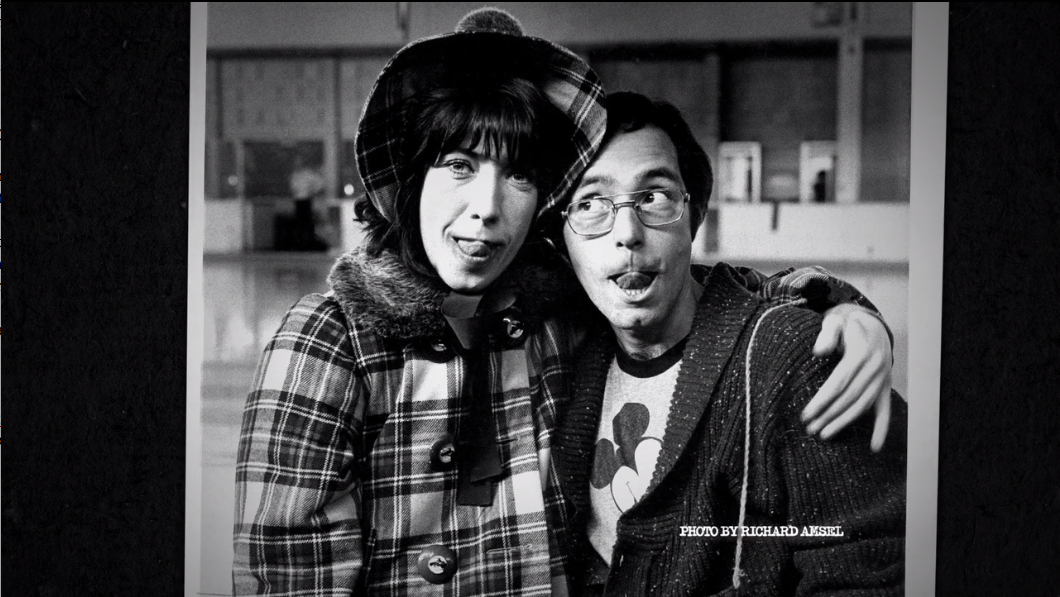

“In 100 years of movies, homosexuality has only rarely been depicted on the screen. When it did appear, it was as something to laugh at, or something to pity, or even something to fear. These were fleeting images but they were unforgettable. Hollywood, that great maker of myths taught straight people what to think of gay people. And gay people what to think about themselves. No one escaped its influence.” - Lily Tomlin in Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman’s documentary based on Russo’s work.

As soon as you hear Tomlin’s words, you know you’re in good hands. Her narration walks you through the “celluloid closet”; that vast archive of films both implicit and explicit that dealt with the love that dare not speak its name on the silver screen. Echoing the Russo lectures he delivered as he was piecing together his magnum opus, Epstein and Friedman offer a history of gay men and lesbian women on screen, from the improbably openness and humor of early films through to the mystery and villainous of the films under the Hayes Code (which censored much of what could be depicted in film) and through to the films that begun in earnest to think about homosexuals.

It is a must-watch for any self-respecting gay cinephile, not only for the sheer amount of footage from old films you should be aware of (that Marlene Dietrich scene from Morocco and that deleted Spartacus scene are particularly wonderful), but because you get to listen to articulate filmmakers and actors who help further contextualize these clips. Russo’s project was never merely a “weren’t all these images of gays horrible?!” but a keener attempt at understanding the impetus behind why they were being produced and the effects they had in the culture at large.

It also has great interviews with many of the actors, directors, and screenwriters involved with many of the films cited. It’s fascinating to hear Shirley MacLaine looking back on Children’s Hour (which we saw in If These Wall Could Talk 2) confessing she and Audrey Hepburn never really addressed the “L” word, especially in comparison to Susan Sarandon’s openness about shooting The Hunger. While the original script called for her character to be drunk — thus excusing her initial dalliance with a woman, she fought for a more measured take.

“You wouldn’t need to get drunk to go to bed with Catherine Deneuve!” she quips.

To say Russo’s work has been invaluable in my own work is a great understatement. Indeed, his catalogue of “sissies,” “villains,” and “sad gays” helped me structure my very own “Gay Men On Screen” supercut, which plays like an updated version of The Celluloid Closet.

HBO was instrumental in helping get Epstein and Friedman’s documentary made (they provided the necessary funding to get the film finished), so it’s no surprise Sheila Nevins, head of the HBO docs, would later greenlight another project focused on the late film historian. Vito, tightly focused on the life and work of Russo, picks up from The Celluloid Closet, offering in fact, a short history of the project as well as a brief summary of its impact while tracing the life story of the writer. It’s an inspiring story to any of us who write about film (did you know his manuscript was rejected over fifteen times?!) and who believe that actively interrogating what cultural artifacts say (or refuse to say) about us is important. Indeed, you might say that's what drives this very history I'm writing.

But it's when Schwarz sketches out Russo’s activism, both as a founding member of Gay Activist Alliance (GAA) and later as part of ACT UP that the documentary becomes a riveting provocation. Russo, as we know, lost his partner to an AIDS-related illness (he was featured in Common Threads) and was later diagnosed with HIV himself. Always at the forefront of gay liberation, Vito Russo emerges as a key figure both to gay American history and the screen history of American gays. It’s a great primer that features some great interviews with many TFE faves as well as familiar faces for us HBO LGBT historians, from Lily Tomlin and Bette Midler, to Larry Kramer and Michelangelo Signorile.

With Vito, Schwarz further cemented himself as continuing the strong documentary work about LGBT life that’s driven much of Epstein & Friedman’s work which we discussed when we touched on their Common Threads a few months back. Since Vito, Schwarz has directed a documentary on John Waters muse Divine and just this year he released Tab Hunter Confidential about the (gay) Hollywood heartthrob; his next project is aptly titled The Fabulous Allan Carr. Carr, for those of you playing at home, is the producer behind such fab hits as Grease and the camptastic Can’t Stop the Music (which we celebrated last year as our April Fool’s choice for Hit Me With Your Best Shot).

Fun Awards Fact: A founding member of the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (otherwise known as GLAAD), Russo was driven by anger and outrage over the depiction of gays in films like Cruising. Following his death in 1990, they instituted the GLAAD Vito Russo Award which was first awarded to Paris is Burning’s director Jennie Livingston. It has since gone to, among others, RuPaul (1999), Rosie O’Donnell (2003), and Cynthia Nixon (2010).

Next week: We look at Cinema Verité, starring Diane Lane and James Gandolfini, a fictional retelling of what some consider to be the very first American reality TV series, An American Family which followed the Louds as they divorced and dealt with their son Lance’s coming out. Watch on HBO Go.