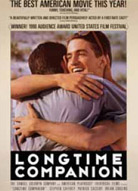

Team Experience is looking back on past Sundance winners since we aren't attending this year. Here's Kyle Turner on an LGBT indie that took the Audience Award and proved so popular in release that it even snagged a Best Supporting Actor nomination (Bruce Davison) at the Oscars a year later.

an early scene in Longtime Companion

an early scene in Longtime Companion

In the first fifteen minutes of Longtime Companion, the words “Did you see the article?” fall from around a dozen different characters’ mouths. It’s July 1981, when the New York Times published its piece titled “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals”, and the way news gets around is by press and by word of mouth. These characters, all gay men in their 20s and 30s, shrug it off, try to carry on with their lives.

To them, this cancer is nebulous, unworthy of their time, and yet something that occupies their thoughts all the same. Thus, the film exists within a particular time, where information is dispersed differently, yet dismissed similarly. Even at the early stages of Longtime Companion’s narrative, the trick is to render these characters sympathetic, even empathetic, and not fall too hard on the line of rhetoric used in Larry Kramer’s divisive novel Faggots.

To them, this cancer is nebulous, unworthy of their time, and yet something that occupies their thoughts all the same. Thus, the film exists within a particular time, where information is dispersed differently, yet dismissed similarly. Even at the early stages of Longtime Companion’s narrative, the trick is to render these characters sympathetic, even empathetic, and not fall too hard on the line of rhetoric used in Larry Kramer’s divisive novel Faggots.

A year later, the hospitals are filled with men, their partners, lovers, and friends in the waiting room or at their side. Time passes, John (Dermot Mulroney) dies, and as HIV/AIDS grows in the lives of these characters – Willy (Campbell Scott), Paul (John Dossett), Howard (Patrick Cassidy), Lisa (Mary-Louise Parker), and Fuzzy (Stephen Coffrey) – the tension between it being the focus of their lives and not allowing it to occupy too much space there serves as narrative propeller.

It’s almost shocking what a tonal difference the film displays in comparison to other plays and films of the AIDS crisis: Parting Glances plays almost as dark romantic dramedy, The Normal Heart as furious and passionate drama, and Angels in America as elegiac opera. But perhaps the key thing to Longtime Companion is that it’s about people struggling to deal with it in the first place, unsure of how to recontextualize their lives in the wake of the epidemic. The dynamics between friends and lovers shift in dramatic ways, and the very act of coping and learning how to cope becomes the film’s core.

Though the characters themselves find themselves orienting and reorienting themselves throughout the film, the film is relatively explicit in its depiction. Its unwillingness to treat the subject in conventional melodramatic terms is to its strength, perhaps rendering the situation as even more devastating: such suffering becomes a part of their lives.

Campbell Scott, and Mary Louise Parker remember their lost friends in Longtime Companion (1990)

Campbell Scott, and Mary Louise Parker remember their lost friends in Longtime Companion (1990)

Longtime Companion, which premiered at Sundance in January 1990, came just before the New Queer Cinema exploded onto the scene. While its lack of fury or aesthetic experimentation separates its from the likes of Paris is Burning, Poison, and The Living End (all of which are credited for kicking off the wave), its straightforward approach, melded with an emotionality that reveals itself slowly but surely, feels like a transgression all its own.

To watch Longtime Companion out of context today is interesting, the assumption being that one is so far removed from the AIDS epidemic. And while significant medical strives have been made and more people are utilizing precautions like PrEP, the history of the AIDS epidemic and its impact shouldn't be allowed to fade from consciousness in the way that it sometimes threatens to. This is a crucial turning point within the narrative of queer history, and the way in which Longtime Companion presents its cast as human beings that transcend easy "victim" labels is the sort of ideology that’s as important as the history itself.

Longtime Companion celebrated its 25th anniversary last year. If you're interested in the film, here is an oral history conducted last year.

Previously on Retro Sundance

Desert Hearts (86), Brave Little Toaster (88), Poison (91), Run Lola Run (99), You Can Count on Me (00), Memento (01), Hedwig and the Angry Inch (01)

Current Sundance

Birth of a Nation, Tallulah, Manchester by the Sea and Christine, Indignation, Certain Women