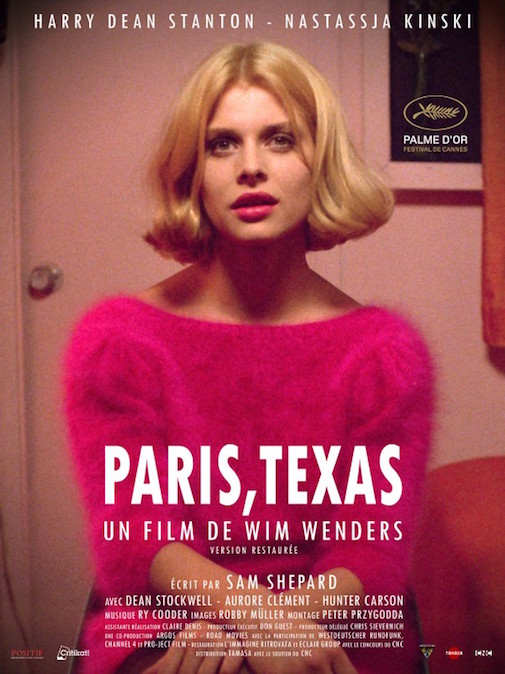

As part of our celebration of the year of the month, 1984, Lynn Lee revisits the winner of that year's Palme d'Or, Wim Wenders' Paris Texas.

While it may not quite have the status of an iconic movie, there’s much about Paris, Texas that feels iconic. A hybrid of those two most iconically American genres, the Western and the road trip—directed, natch, by a German and starring two European actresses—it bears the distinctive features of both. The long stretches of silence, only occasionally broken by snatches of spare Sam Shepard-scripted dialogue or, as often as not, monologue. Ry Cooder’s haunting slide-guitar score, which seems to meld with the harsh, lonely, yet strangely sublime landscapes of Texas deserts, highways, and roadside motels. The lighting, especially at dusk. The weathered countenance of Harry Dean Stanton—how does it manage to be at once so stoic and so expressive?—and the exquisitely sculpted planes of Nastassja Kinski’s face, as they quiver and dissolve in the movie’s most emotionally wrenching scene.

While it may not quite have the status of an iconic movie, there’s much about Paris, Texas that feels iconic. A hybrid of those two most iconically American genres, the Western and the road trip—directed, natch, by a German and starring two European actresses—it bears the distinctive features of both. The long stretches of silence, only occasionally broken by snatches of spare Sam Shepard-scripted dialogue or, as often as not, monologue. Ry Cooder’s haunting slide-guitar score, which seems to meld with the harsh, lonely, yet strangely sublime landscapes of Texas deserts, highways, and roadside motels. The lighting, especially at dusk. The weathered countenance of Harry Dean Stanton—how does it manage to be at once so stoic and so expressive?—and the exquisitely sculpted planes of Nastassja Kinski’s face, as they quiver and dissolve in the movie’s most emotionally wrenching scene.

That last aspect is at once the film’s ace and its Achilles heel. By the latter I don’t mean Kinski’s acting (I think she’s fantastic, shaky Texan accent aside) or the writing of that particular scene. Rather, I mean the conception of her character, Jane, and Jane’s relationship to Stanton’s wanderer Travis, which culminates in that scene.

If the first two thirds of Paris, Texas are about Travis’ reconnecting with his brother and young son as he slowly comes back to life, the last third is dominated by his efforts to find Jane...

And find her he does. But unlike the other major characters, Jane never appears on her own, free of another character’s mediating gaze. She’s always, always presented as an image controlled and viewed by someone else, whether it’s Travis, looking through the one-way glass of the peep show booth, their son Hunter looking at her in her car at the bank drive-through, or the Super8 camera that forms and fixes Hunter’s memory of her, even if the boy is perceptive enough to realize “that’s not her. That’s only her in a movie.” It’s a recognition later echoed by Travis, deep in the cups after the initial shock of seeing Jane again, as he reflects aloud to Hunter on his own mother and his father’s inability to see her for what she really was, rather than the image he created of her – “the girl from Paris.”

Travis’ response, arguably, is to free Jane from the same fate. Yet there’s something a little disquieting about the fact that his decision is sandwiched between two interactions with her that frame her within the hyper-artificial confines of the peep show booth—scenes purporting to be in a “hotel” and a “coffee shop” that look like a cheap postcard of an Edward Hopper rip-off. (Side note: Daniel should really consider doing an installment of “The Furniture” on this movie.) Indeed, there’s something downright creepy, at nearly David Lynch levels of weirdness, about their first meeting in this sad, seedy world, in which he can see her but she can’t see him. True, he reverses that uncomfortable dynamic on his second visit by turning his back to her so he can’t see her as he reveals who he is, and then by telling her to turn out the light so she can see him. Even then, though, it says something that the most striking visual image in that scene is the superimposition, on the glass, of his face over Jane’s—as if to emphasize that we still can’t really see her; we can only see her effect on him.

And then there’s that ending, which to me comes off as simultaneously forcing Jane to assume full parental responsibilities for Hunter while ripping them away from the kid’s loving foster parents. Again, it’s possible to look at as Travis’ way of giving rather than denying agency to Jane, by presenting her the choice of what to do. (Even if it comes at the expense of Hunter’s other parents, not to mention Travis' own as a father.) Yet that choice is still fundamentally controlled and orchestrated by Travis, not Jane; even her poignant reunion with her son is still framed by the presence of Travis, watching from afar.

All of which may be merely to say that first to last, this is Travis’ story, not Jane’s. Nothing wrong with that. But it underscores why Paris, Texas feels to me so much like a man’s story, written and made by men, and crafted to appeal to men, rather than the more universal narrative of breaking and mending human connections it’s commonly held up to be. In that sense it’s wholly keeping in with the tradition of both Westerns and road trip films. Still, as I watch it now, I can’t help thinking of that other Western/road trip classic that would come only seven years later, Thelma and Louise, as the perfect answer and counterpoint to those traditions—embodied, in Paris, Texas, in a Jane who never got a gun.