by Eric Blume

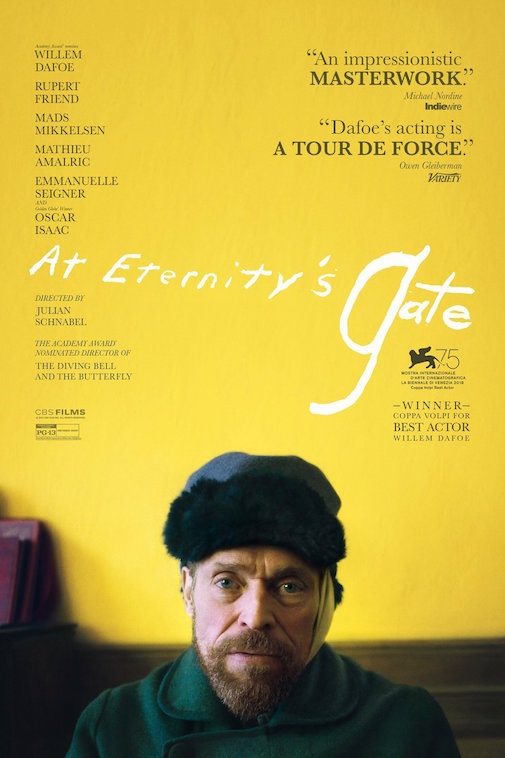

Willem Dafoe plays Vincent van Gogh in At Eternity’s Gate, director Julian Schnabel’s film about the last year in the life of the great Dutch painter. And Dafoe’s delivers a magnificent performance here: his face is the canvas of the film, in all its agony and ecstasy.

Willem Dafoe plays Vincent van Gogh in At Eternity’s Gate, director Julian Schnabel’s film about the last year in the life of the great Dutch painter. And Dafoe’s delivers a magnificent performance here: his face is the canvas of the film, in all its agony and ecstasy.

Schnabel, a painter himself who made the stunning films Before Night Falls and The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, gives us a deeply detailed movie of a painter by a painter. The mechanics of landscape and portrait painting, the walks to the viewpoints, the tools, and the intimacy with the subject all become the fabric of this movie. Schnabel’s attention to these subtleties establish his credibility and give the movie real texture...

What Schnabel wants to do is get inside van Gogh’s head at time of his mental unraveling: literally. He shoots the entire movie handheld, which when you’re not feeling vertiginous, allows for close-ups of Dafoe so tight that you’re almost actually inside his head. At one point, in a climactic scene between Dafoe and Oscar Isaacs (who plays Paul Gaugin), Dafoe becomes the camera: Isaacs plays straight down the barrel and we feel van Gogh processing this information as if it’s coming straight at us (because it is).

This technique may likely be a bit too much for some people, but it strips the romanticism out of van Gogh’s story. If you know anything about van Gogh at all, you know about how he cut off his own ear, about the mental instability, and the Provence paintings. Over a hundred years later, it’s easy to put van Gogh’s story in a easily-filed column of the lonely, tortured artist who died penniless but then became of the world’s most famous painters after his death.

But in At Eternity’s Gate, Schnabel demystifies that story. He thrusts you headfirst (again, literally) into van Gogh’s desperate loneliness, his inability to react properly to almost any other human outside of his brother (played by Rupert Friend). And he attempts to get to the root of what “tortured artist” really means: he and Dafoe portray this pain with a bottomless abyss of fear and terror, but also with a sense of confusion and awe. They’re getting at something really complex here, without offering any simple answers but diving into the heart of a mind slipping away.

The film is absolutely gorgeous. It’s true that Schnabel works at a languorous pace, but once you adjust to his tempos, you get lost in this movie, and my heart was in my throat for van Gogh on many occasions. And Schnabel stages a scene with Dafoe and Friend, where the brothers lay cuddled in bed in each other’s arms, with a tenderness that’s nearly unbearable.

Dafoe should be at the top of every Best Actor list this year. A lesser actor would have turned this role into a showy tour-de-force, with the emphasis being on oversized emotions. Dafoe shows us, instead, van Gogh’s wonder of nature, the euphoria in painting. Joy and pain are inseparable for this interpretation; they drive the artist equally. In the scene where he explains cutting off his own ear, Dafoe shows us a man who feels his action is both easily rationalized and also inescapably esoteric. There’s no “playing crazy” in Dafoe’s star turn. The artist is as bewildered as anyone by what comes over him, and the desperation Dafoe plays in his isolation is deeply stirring. Dafoe’s van Gogh can’t reach people but he keeps urgently trying, through his painting, the only thing he knows how to do. It’s a monumental performance in a beautifully-made picture.