Hi, we’re John and Matt and, icymi, we are watching every single live-action film starring Streep...

#6 — Sarah Woodruff, an outcast of ill repute in Victorian England, and Anna, the philandering actress playing her...

JOHN: The French Lieutenant's Woman (1981) was Meryl Streep’s first starring role. Karel Reisz, a Czechoslovakian director steeped in British kitchen-sink realism, took a swing at John Fowles’ 1969 postmodern novel, adapted liberally by playwright Harold Pinter. I have not read the novel, but from what I understand the behind-the-scenes thread is an entirely original invention by Pinter in an attempt to echo the novel’s feminist deconstruction of Victorian social mores by displacing them onto a modern setting. Fowles’ novel interrogates the conventions of spurned women like Sarah Woodruff in this type of historical literature, working as an autocritique of period novels and offering the reader the choice between three endings, highlighting the authoritative control authors possess and juxtaposing past and present attitudes on gender and sexuality. It sounds like a great read! Likewise, it would seemingly produce a challenging and subversive film. But then you put in the DVD.

I have tried twice now, but nothing about The French Lieutenant’s Woman at all resembles what critics praise about the novel. I see no authorial innovation, no bold challenges to social mores, no scenes of explosive romance, no postmodern triumph, and certainly no performances of note. In her first leading role, Streep struggles with a dull screenplay and flounders amid undermining direction. Streep just can not cohere the competing versions of Sarah spoken by everyone in the script, and indeed can not reconcile all of this with Sarah’s own admissions. Is she really a “remarkable person?” Does she believe this for one moment? Is she the willful homewrecker? The heedless town whore? The humiliated ex-lover? The frightened outcast? From scene to scene, Sarah makes less sense. Her character is routinely deemed “mysterious” and Streep was praised for precisely this effect; but when is “mystery” merely incoherence disguised as complexity?

Here is where the already dire mess of a character truly unravels: the scenes involving Anna, the American actress who is playing Sarah and engaged in an affair with her co-star (Jeremy Irons), undercut Streep’s Sarah by pointing out how affectedly put-on and wonkily accented the majority of her performance really is. When folks criticize a Streep performance, they often point to her surface-level technique, her over reliance on accents and skillsets, and the sense that she’s “working hard” and therefore lacking a certain soul or hot-blooded body underneath the character. We’ll have time to address these warranted and unwarranted criticisms in her filmography, but what is most off-putting about this specific performance is how the Anna plotline sabotages Streep’s attempt to develop a distant period character in a titillating romance. We see the carefree, relaxed, and utterly modern Anna followed by the strenuous and very Victorian Sarah, as Streep’s technique and faulty accent quickly reveal themselves. Her Sarah, continually caught in desolate poses and spewing risible dialogue, is simply set up to fail. Combined in one film, Sarah Woodruff and Anna just cancel each other out. If the film’s goal is to comment on the artificial nature of filmmaking, it succeeds in this regard by sabotaging the attempts of all of its actors, Streep included, to carve out a substantial performance.

MATTHEW: I am in near-total agreement about this fitfully striking but psychologically obscure performance and the hopelessly muddled film that produced it.

JOHN: Well, in that case…

MATTHEW: Very well then. While not as iconic as later Streep turns in Sophie’s Choice or Silkwood, The French Lieutenant’s Woman holds special significance for many Streep worshipers. Others probably know it best for that fairly famous medium shot of Streep, hooded, a shock of red hair peeking out at the top, as she stands against the oppressive grey of an English sky and glances behind her shoulder to look at Irons, her eyes locking with the camera. It’s a postcard image of Victorian inscrutability, but it also foreshadows the fundamental conundrum of the film and Streep’s performance, which even she has trouble supporting. Pinter’s cerebrally over-judged structural conceit enforces a purposeful dichotomy of two very different performance styles amongst all of its actors: the stately affectation of the film and the casual naturalism of the behind-the-scenes glimpses. I don’t think anyone in the ensemble fares particularly well under this assignment, including Irons, who mostly chomps on the scenery (and his consonants) in an excessively showy performance that privileges a type of stage-honed technique which remains forever discernible, even in the present-day passages. Streep suffers a similar fate, but that doesn’t really seem to be her fault so much as Reisz’s.

In separate video interviews with The Criterion Collection for its 2015 release of The French Lieutenant’s Woman, both Streep and Irons were quick to comment on the unobtrusive directorial style of Reisz, a gentle prodder of actors who steered away from any forthright direction, like, say, suggesting a line reading. In her interview, Streep recounts a particularly revealing experience, in which her failure to convincingly say the aforementioned line, “Yes, I am a remarkable person,” during a pivotal scene in an undercliff, resulted in twenty-plus takes of the same line, throughout which Reisz offered little to no guidance to his increasingly exasperated leading lady. And it shows. The final product just doesn’t convince as Streep’s breathy delivery apes the type of refined, Masterpiece Theatre polish that the actress never fully pulls off.

JOHN: That line-reading is indeed lacking, second only to the completely hilarious, “I am the French Lieutenant’s whore!” Did you know that Fowles actually thought Vanessa Redgrave would be the ideal Sarah? "Inside Oscar" recounts the divided critical responses in ‘81: “The Long Angeles Herald-Examiner raved, ‘We can believe this woman is all things - crazy, visionary, pure, despoiled - because Streep has incorporated all the possibilities into her performance.’ But the New York Daily News thought the actress ‘seems somewhat constrained for a woman who is supposed to represent the untamed forces of nature.’”

I’m not sure exactly how Sarah Woodruff could be considered crazy and pure and untamed, three different adjectives used to depict a performance that only fitfully wrestles with such descriptions, or maybe “all the possibilities” is just shorthand for “this is merely the first draft of a character.”

For me, Sarah is first and foremost the dejected object of smalltown gossip, a heartbroken woman whose French lieutenant (an entirely remote figure) left her behind to fight the battles on her own, unequipped in many respects to stand her ground. The reckless libertine hinted at by both townsfolk and the film’s reviewers is a concept as elusive as that French lieutenant. Could Redgrave have done any better? Could someone like Isabelle Adjani maybe have ironed out the hypocrisies of the character and really dug into her psyche in a compelling way? Perhaps. But this is less Streep’s failure and more the result of a scattershot script.

MATTHEW: “[S]omething about [Streep] puzzles me,” wrote Pauline Kael in her pan of the following year’s Sophie’s Choice. “[A]fter I’ve seen her in a movie, I can’t visualize her from the neck down…she in effect decorporealizes herself.” I don’t agree with this critique, but I can see in Streep’s stiff-featured work here, more than any other performance, the basis and reasoning behind Kael’s notorious assertion that Streep turns screen acting into a mechanical and excessively-studious art form. Streep’s interpretation of Sarah is far too decisive, cutting off any opportunities for moment-to-moment spontaneity. She is certainly helped by neither Reisz nor Pinter, whose needless framing device only undermines any emotional investment from the audience. But I still cannot understand why Streep is seemingly unable to perform simple movements like swinging around a tree or clinging to a bedpost without looking wooden and over-rehearsed?

Streep is, of course, far too masterful an actress for this performance to be an entire botch, especially when the script asks her to play something more than obvious misery. In a key scene in which Sarah sits in the forest with Charles, Irons’ enraptured palaeontologist, and recounts her tragic liaison with the titular lieutenant, Streep relaxes her physical carriage and gets more playful with her gestures and expressions. I liked her later reaction upon seeing Irons for the first time in a hotel after a long absence, the agony of which is felt quite palpably in Streep’s quiet, open-mouthed surprise. There is also a remoteness to her real-life actress that is far more interesting than the fictional character with whom we spend so much more time. Anna’s occasional coolness — and the trepidation it masks from Irons — invites actual speculation, whereas her cinematic Sarah is utterly, woefully lacking in necessary mystery, her nebulous nature failing to inspire any actual intrigue. Is Streep’s almost unceasing stiltedness as Sarah a meta-comment on Anna’s own discomfort at identifying with a dishonest, guilt-ridden adulteress, a part which she comes to melancholically play in her own life? Or is Anna just an unduly opaque actress whose frizzy, unkempt wig feels more distinctive than any of her performance choices? Either way, there is a visible gap between Pinter’s conception of Sarah and the one rendered on screen by Streep, who never looks like she has invested nearly enough of the complexity that elevated earlier roles in The Deer Hunter and Kramer vs. Kramer from evidently male-invented female characters to actual, rounded human beings.

JOHN: She’s weirdly playful in the forest, but it's a tactic that feels entirely misplaced. I love a good Meryl Emotional Flooding, where her overwhelming feelings seem to assault her and demand release by face-touching, eye-darting, and hand-wringing, but in this moment those all come across as nervous tics out-of-step with the character. And what of her scheming in that graveyard with Charles, trying to pass herself off as a both a sinful heathen and a cunning, wicked creature, while sporting a sable hooded cloak that perfectly anticipates her Into the Woods costume? “I have a freedom they can’t understand,” she says at one point, directly referencing the audience held captive as viewers to this muddled spectacle.

MATTHEW: “It was as if her torture had become her delight,” a doctor says of Sarah in one early scene, suggesting a masochistic streak in the character that never registers in Streep’s performance. Indeed, so little registers in Streep beyond the prepossessing suffering that we witness early on in that well-known shot that introduces Sarah to Charles as an inscrutable enigma. The trouble with The French Lieutenant’s Woman is that no one involved, including an unusually adrift Streep, has envisioned Sarah as anything deeper.

Not all filmic puzzles need to be solved but there is a sizable difference between positing a real mystery of the heart and throwing up a cloud of smoke in the same place where a fully-realized woman should be standing.

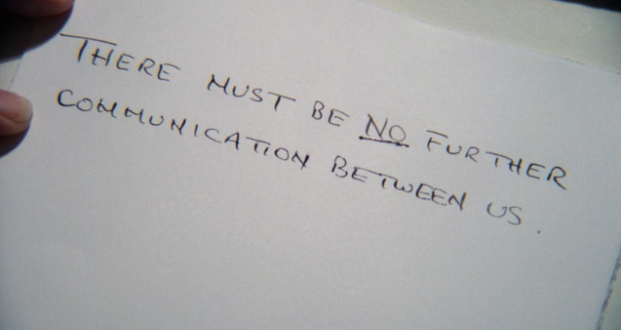

JOHN: I will admit that Anna’s tense meeting with Mike’s wife at a late-film cast party is a moment worth preserving, but almost all of the real-world scenes softly float by on Streep’s undisputed charm and poise, ultimately leaving only a vague impression. When Sarah finally gets a room of her own at the film’s end, traces of a livelier, more defiant woman hint at what could have been all along. For most of the film, Sarah is a mystery to solve, the psychological dilemma of Charles’ unscrupulous inquiry, and is therefore trapped emoting tearfully on bundles of hay, until she finally breaks free. Hopefully her new self-portraits won’t be too hostile. Maybe she can paint a portrait of nationalism, Darwinism, the artificiality of novels, the plight of women in the 19th century, forbidden love, and class warfare, and still manage to be compelling and coherent. That’s a painting I would have liked to see Streep paint and a fiction I’d choose over this reality.

Reader, has Streep’s torture become your delight? Is her Sarah Woodruff actually a remarkable performance? Share your thoughts in the comments.

Previously: Julia, The Deer Hunter, Manhattan, The Seduction of Joe Tynan, Kramer vs. Kramer