John and Matthew are watching every single live-action film starring Meryl Streep.

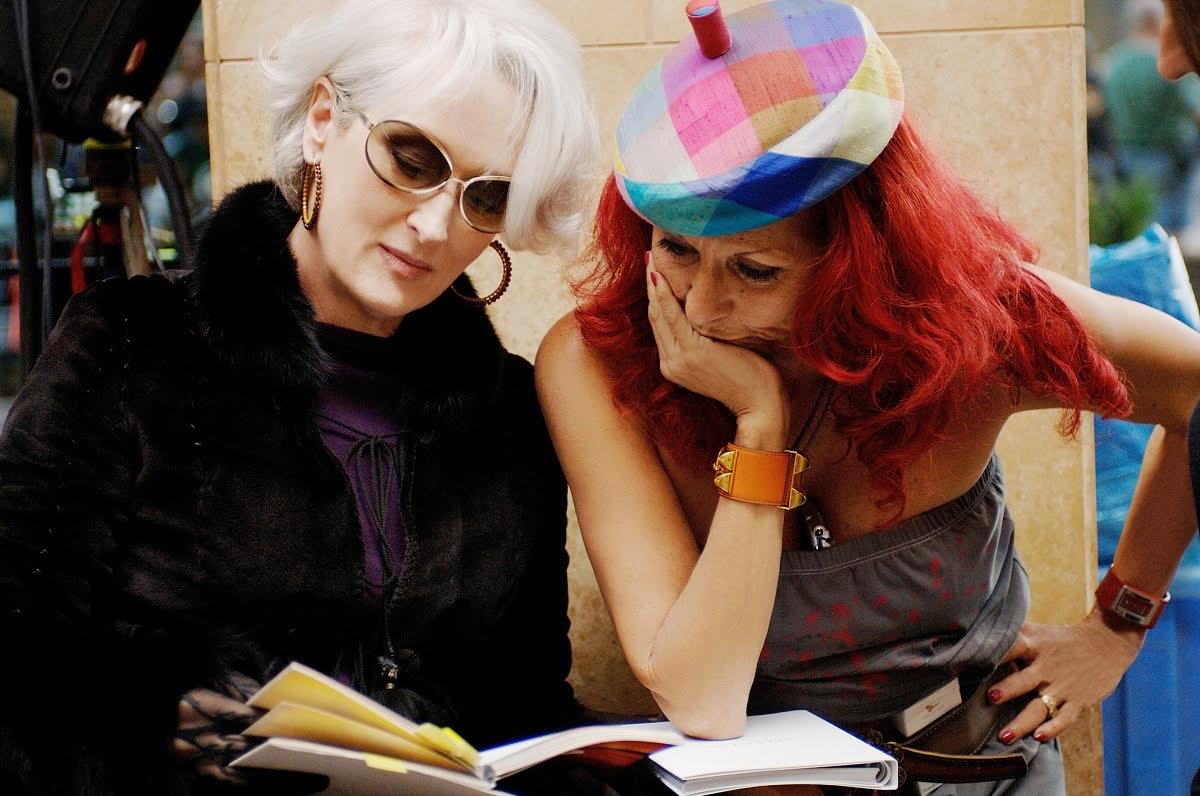

Meryl talking to director David Frankel during shooting

Meryl talking to director David Frankel during shooting

#34 —Miranda Priestly, ferocious editor-in-chief of Runway magazine.

JOHN: How do you solve a problem like Miranda Priestly? Or, more specifically, The Devil in Prada? How do you make walking into a room a distinct and indelible character trait? How do you continue assembling a mannequin’s outfit while simultaneously delivering a brutal lecture about the color cerulean? How do you not only resist but upend the misogyny inherent in your role? How do you grip the audience by their necks while still having them root for your victory? When your name is Meryl Streep, such issues are not problems or challenges, but more like Smith & Wollensky porterhouses, plump, juicy, bloody gifts, presented to you on a plate...

Forget the fact that Miranda is actually the side dish to Anne Hathaway’s entrée as Andrea “Andy” Sachs, new assistant to Miranda Priestly. Streep glides through The Devil Wears Prada with Olympian vigor, not breaking a sweat as she effortlessly hurls outrageous demands, outright insults, and posh coats as if by second nature, all while looking unimpeachably glamorous. That being said, Streep’s Miranda Priestly is not “the devil.”

Streep’s performance is an extraordinary recuperation of the harridan, unemotional female authority archetype and a corrective to entrenched cultural beliefs that powerful women are heartless bitches.

Streep almost single-handedly rewrites Miranda away from the vindictive, power-mad boss from hell, depicting her instead as a powerful woman at the top of her game with no time or patience for anything less than the high standards she keeps for herself and expects of her underlings. In an interview with The Sunday Telegraph, Streep explained how she based Miranda on powerful male executives she had met in the film business. “Unfortunately we don’t have enough women in power, so most of my models for this character were of the male persuasion,” she says. “The anticipation for the film is almost bloody in that people are longing to go after Anna Wintour, or any woman in a powerful position. People love this story because they think that the knives are out, and that makes for good anticipation at the box office. I was interested in portraying a woman in a powerful position, and showing exactly how hard she has to work to stay there.” While recognizing Miranda’s abhorrent qualities are par for the course in her industry, Streep tries her absolute hardest to make viewers sympathize with Miranda’s drive for total perfection in her work. In the same interview, Streep elaborates, “Personally, I think that she’s an exacting, highly disciplined, demanding and ambitious person… and, in many ways, [I am] the polar opposite of this character. And yet I really understand her.”

Beside humanizing a potentially monstrous figure, Streep’s Miranda is an uproarious comic performance, an unflappable marathon of killer glances and ruthless one-liners as iconic as anything Streep has ever done. Even when given a riotous line or sight gag, Streep plays these moments as if she cannot be bothered to play them at all. In her centerpiece “cerulean” monologue, Streep never stops assembling the outfit at-hand; to do so would mean to dignify Andy with her full time and attention. The character can be unwittingly obtuse, like when she’s demanding to be flown out of a Florida hurricane, but also deliberately heartless, as in the myriad times she refers to Andrea as “Emily,” the name of her primary assistant, superbly played by Emily Blunt in her breakout turn. Miranda’s attitude towards Andy alternates between callous indifference (“Has she died or something?”) and out-and-out cruelty (“I said to myself, go ahead. Take a chance. Hire the smart, fat girl.”) My favorite line changes every week, but for today I’ll go with, “Get me that piece of paper I had in my hand yesterday morning.”

Beside humanizing a potentially monstrous figure, Streep’s Miranda is an uproarious comic performance, an unflappable marathon of killer glances and ruthless one-liners as iconic as anything Streep has ever done. Even when given a riotous line or sight gag, Streep plays these moments as if she cannot be bothered to play them at all. In her centerpiece “cerulean” monologue, Streep never stops assembling the outfit at-hand; to do so would mean to dignify Andy with her full time and attention. The character can be unwittingly obtuse, like when she’s demanding to be flown out of a Florida hurricane, but also deliberately heartless, as in the myriad times she refers to Andrea as “Emily,” the name of her primary assistant, superbly played by Emily Blunt in her breakout turn. Miranda’s attitude towards Andy alternates between callous indifference (“Has she died or something?”) and out-and-out cruelty (“I said to myself, go ahead. Take a chance. Hire the smart, fat girl.”) My favorite line changes every week, but for today I’ll go with, “Get me that piece of paper I had in my hand yesterday morning.”

There is so much to say about Streep’s performance, and I’m interesting in hearing about your ambivalence toward Miranda. Have you sorted out your feelings about the role and the performance? Shall I gird my loins?

Streep discussing Miranda with Oscar nominated costume designer Patricia Field

Streep discussing Miranda with Oscar nominated costume designer Patricia Field

MATTHEW: Let me clarify that my ambivalence towards the notorious Miranda Priestly has less to do with Streep’s sensational, career-revitalizing interpretation, which manages to find a real woman inside this supposed villain, than it does with the film itself, which casts away the cartoonishly warped Devil of Lauren Weisberger’s gossipy, condemnatory source material but occasionally mistakes oversimplification for humanization in the process. Streep, for her part, had little time for Weisberger’s fictionalized tell-all: “I thought it was written out of anger and from a point of view that seemed to me very apparent,” Streep told W magazine. “The girl seemed not to have an understanding of the larger machine to which she had apprenticed. So she was whining about getting coffee for people. If you keep your eyes open [in that situation], you’ll learn a lot. But I don’t think she was interested.”

Streep, along with screenwriter Aline Brosh McKenna, discarded a great deal of Weisberger’s Miranda, using this frothy but utterly engrossing adaptation as a glorious excuse to employ her unbridled creativity in the invention of a distinctive new character. Seeking to put as much distance between her fictional antagonist and Wintour, the real-life inspiration, Streep swapped the latter’s British accent for an American one, giving her Miranda a calm, menacing coo of a voice that the actress later claimed to have stolen from, of all sources, Clint Eastwood. Together, she and the great J. Roy Helland conceived of the character’s cropped, snow-white locks, drawing on everyone from the now-octogenarian model Carmen Dell’Orefice to Helen Mirren, the performer who ultimately bested Streep to that year’s Best Actress Oscar. She encouraged McKenna and director David Frankel to stop pulling their punches and heighten the character’s difficult behavior. On set, Streep threw herself into the part with focused commitment, icing out Hathaway once the cameras started rolling and often veering off-script in order to keep her film’s true leading lady on her toes.

Hathaway, playing a clear, refreshing, and necessary center of normalcy, received tepid praise at best when Devil arrived in theaters in the summer of 2006. It quickly became an unanticipated critical and commercial smash, over the years acquiring a loyal and slightly rabid fan base that includes John Krasinski, Ludacris, Nicki Minaj, and Chrissy Teigen and John Legend. This is a victory almost exclusively attributed to Streep’s legacy-enshrining tour de force, which is understandable if a tad unfair. Frankel’s filmmaking is average to the point of depersonalizing, leaving it up to his actors to give the film personal verve and dapper detail. Hathaway, Blunt, and Stanley Tucci, perfectly amusing as Runway art director Nigel, each deliver, picking up their director’s slack and offsetting some vanity-stoking turns by Simon Baker and Adrian Grenier. But, yes, it’s impossible to talk about Prada without returning to its raison d’être, which is Streep, who makes her every moment indelible, whether she’s flinging down those coats and bags with violent force or even managing to hang up a phone with a flourish. We, in turn, relish her appearances, which are fewer than one might expect, and impatiently anticipate her reemergence into the movie.

As Miranda, Streep finds all the right ways to fill a frame with imposing majesty while appearing to do the bare minimum with her composed and contained body, held upright with a dancer’s swanlike grace. Well within her third decade of screen acting, Streep knows exactly how much to feed the eye of the camera, aware that few things are more alluring than an actor’s willful detachment — and her inevitable, revealing deviations. Take the scene where Andy walks in on a domestic spat between Miranda and her soon-to-be ex-husband while dropping off the mock-up of the magazine’s latest issue: Streep’s eyes do nothing more than alight and freeze with horror as Miranda realizes her private life has been exposed in front of her guileless new assistant, the horror of having inadvertently confirmed her human vulnerability to someone meant to see her as infallible. Certain choices give the impression that Streep hasn’t embedded herself enough into the character’s glacial remove or perhaps shown her hand too easily: smirking with tiny, newfound delight at Andy’s high-fashion makeover or, later, raising her brows, batting her eyelids, and stroking her glasses across her chin with game-recognizing-game surprise at Andy’s Harry Potter coup. This Devil may at times be too easy to read and root for, but by occasionally dropping the ice queen routine, Streep distinguishes her scenes, if only in the subtlest ways, in order to show us new facets of what could have easily been a flat villainess. It matters when Miranda’s mask slips because Streep is actively using these moments to describe something previously unknown to us, like the character’s ability to be swayed by professional competence or her nervous, stuttering timidity in the face of Jacqueline Follet, rival editor of French Runway.

Tell me your thoughts about the most decisive slip of this mask — the scene in which Miranda, bare-faced like a kabuki queen scrubbed clean of her makeup, cries over the end of her marriage.

JOHN: When Andy enters Miranda’s hotel room to find her in sweatpants, sans makeup, eyes swollen, and surrounded by tissues, the sight of this alone is cause for alarm, but it gets worse: Miranda has just been sent divorce papers from her third husband. Streep, in a scene she herself solicited, adds a more vulnerable and lonely shade to Miranda’s character while still retaining the character’s essential aloofness. (Streep called it “the part of the film that makes the whole rest of it worth doing. Without that scene, what is there?”) Miranda reveals that her ex-husbands are at first attracted to her power and confidence, only to be later repelled by the same qualities. Miranda is especially saddened for her daughters, who will have to say goodbye to yet another “father figure” and be exposed to bilious articles commenting on their mother’s frigid and contemptible demeanor. In what is essentially her “deglam scene,” Streep demonstrates her incredible knack for cutting right to the emotional core of a character to reveal the humanity beneath a difficult woman, a preoccupation and career-long project that underscores many a Streep performance.

Though it is ultimately questionable that audiences needed this scene to emphasize Miranda’s humanity (Was Miranda not a human when she was instead wearing those Saint Laurent suits and calling the shots?) this moment nonetheless excises Miranda’s “villainy” from the film, an unexpected achievement that, as you’ve mentioned, deviates from the source material and feels generated by Streep herself. In the following scene, Andy defends Miranda from Christian’s (Baker) criticisms of her boss as merely a harsh and unfeeling tyrant, rightly pointing out that “you wouldn’t be saying that if she were a man. You’d be admiring her strength, her grit, her tenacity, but because she’s a woman, those things make her a ‘ball-buster.’” I’m glad the script dares to utter such a disparity between conceptions of powerful men and powerful women, but feel disappointed that this valid claim is swallowed up by a swoony sex montage and never addressed again. Miranda’s last-act scheme to upend Jacqueline Follet’s and her confidante Nigel’s promotions in a nasty bit of onstage maneuvering blots out Streep’s work to dimensionalize Miranda as anything other than a calculating despot. And finally, when Andy frees herself of Miranda because of this very scheme, we’re meant to celebrate her departure into “real journalism” and scorn Miranda’s return to her slow-mo paparazzi cocoon, as the dragon lady finally folds herself back into her dark chambers, sealed off from the world while Andy confronts it via a hardscrabble newspaper job.

MATTHEW: I’m of two minds about Miranda’s “crying” scene. As written, it reads as a slightly reductive scene, one of those strenuous Humanizing Moments in which the appearance of big, salty tears is meant to convey some sort of truer self lurking beneath the elegant surfaces of this hostile woman. The scene wants to expose the real Miranda Priestly, but is that to say that this more vulnerable Miranda is more authentic than the one who quietly upbraided Andy for daring to think she was somehow above the “stuff” that defines the industry to which Miranda has devoted her life?

MATTHEW: I’m of two minds about Miranda’s “crying” scene. As written, it reads as a slightly reductive scene, one of those strenuous Humanizing Moments in which the appearance of big, salty tears is meant to convey some sort of truer self lurking beneath the elegant surfaces of this hostile woman. The scene wants to expose the real Miranda Priestly, but is that to say that this more vulnerable Miranda is more authentic than the one who quietly upbraided Andy for daring to think she was somehow above the “stuff” that defines the industry to which Miranda has devoted her life?

If you listen close enough to Streep during the “cerulean” monologue, which strikes me as the most revealing moment in the entire performance, you’re likely to hear a fiercely honest defense of an entire profession, one given further credence by the glowing conviction of Streep’s reading.

Streep works her brilliance again as Miranda bemoans her latest divorce, achieving a thorny poignancy that complicates the conversation, betraying and deflecting from Miranda’s sensitivity at her own measured pace. When Andy, oozing unabashed empathy, asks Miranda if there’s anything else she can do, Streep’s forbidding rejoinder — “Your job” — rewrites this scene from a simple unmasking to a doubling-down of Miranda’s purpose: broken marriages and hurt feelings may be the cost of her work, but Miranda won’t forfeit professional glory for the sake of a happy home life — or even lasting friendships, as her casual sacrifice of Nigel will later prove. Watching Streep beam with flashes of genuine, conspiratorial warmth in the backseat beside Hathaway during their final dialogue scene together, we realize that Miranda is grateful for Andy’s loyalty but perhaps even more pleased to be in the company of another ruthless go-getter.

The actress layers this scene like she does every other, letting Miranda’s guard down with Andy to express sincere admiration before using a single, well-appointed gesture (in this case, the donning of sunglasses) to signal the reassertion of the boss-assistant barrier. Streep’s performance is full of moments in which a condensed yet conspicuous choice clues us in to a character who might have been continually kept at a distance. Even in this comparatively minimalist turn, we see the work, the decision-making, that unites all of Streep’s performances. When Miranda purses her lips in horror, narrows her eyes into a withering glare, or relaxes her face into the tiniest of grins, these choices mean something and Streep has made her approach transparent enough for viewers to decipher such meanings. Maybe this is why The Devil Wears Prada remains such a valuable staple for young audiences, any number of whom might be aspiring actors eager to see how a screen performance is put together, piece by piece, choice by choice. Many of Streep’s harshest critics have used the legibility of her style as ammunition against the actress. You know, “wheels turning” and all that. But just because the magician occasionally lets us look behind the curtain doesn’t make the act itself any less magical.

Catch up with 'Months of Meryl'

- Julia (1977)

- The Deer Hunter (1978)

- Manhattan (1979)

- The Seduction of Joe Tynan (1979)

- Kramer vs Kramer (1979)

- The French Lieutenant's Woman (1981)

- Still of the Night (1982)

- Sophie's Choice (1982)

- Silkwood (1983)

- Falling in Love (1984)

- Plenty (1985)

- Out of Africa (1985)

- Heartburn (1986)

- Ironweed (1987)

- A Cry in the Dark (1988)

- She-Devil (1989)

- Postcards from the Edge (1990)

- Defending Your Life (1991)

- Death Becomes Her (1992)

- The House of the Spirits (1993)

- The River Wild (1994)

- The Bridges of Madison County (1995)

- Before and After (1996)

- Marvin's Room (1996)

- Dancing at Lughnasa (1998)

- One True Thing (1998)

- Music of the Heart (1999)

- Adaptation (2002)

- The Hours (2002)

- The Manchurian Candidate (2004)

- Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events (2004)

- Prime (2005)

- A Prairie Home Companion (2006)