by Nathaniel R

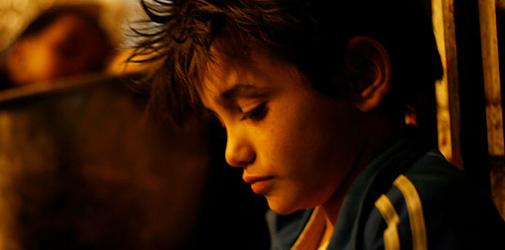

Nadine Labaki is three-for-three. Lebanon's most prominent filmmaker has seen all three of her films premiere at Cannes to considerable acclaim and go on to represent her country as Oscar submissions. The first two Caramel (2007) and Where Do We Go Now? (2011) became international arthouse hits. Her newest feature Capernaum, distributed by Sony Pictures Classics, recently began its platform release in the US and will hopefully see the same warm reception. It's her best shot yet at an Oscar nomination, having made the finals in foreign film. Her Cannes jury prize winner looks at the refugee crisis in Lebanon by focusing on one Syrian boy named Zain (played by Zain Al Rafeea) who is trying to survive on his own. It's a visceral must-see and should elevate Labaki's already healthy reputation as a world class director.

To my surprise, she isn't sure what she's doing next, admitting that this one has been particularly hard to let go of...

Partially that's because she's still advocating for government changes at home around the refugee crisis and doing work to make sure the whole cast is in school and taken care of. Though she's always directed her own material, she recently signed with CAA and might consider other people's scripts, joking that it would have to connect with her on a deep level because "I get ten years older on every film."

Our interview, edited for clarity and length, follows.

NATHANIEL R: In America there's a lot of intense discussion about how female directors don't get opportunities. That doesn't seem to be as much of a problem overseas.

NATHANIEL R: In America there's a lot of intense discussion about how female directors don't get opportunities. That doesn't seem to be as much of a problem overseas.

NADINE LABAKI: It's surprising. I've never felt my job was difficult because I'm a woman. It's just a difficult job in Lebanon, for male or female filmmakers: there's no film industry, no money, no structure. If you come from a small country -- I remember in school, a teacher would point at Lebanon on the world map and say 'You see this invisible dot? It's Lebanon. It's where you come from.' It creates this challenge for you to say 'No, I'm not invisible. I'm going to be very visible.' This gave me a lot of strength. I never projected fragility. There are actually more women than men in Lebanon making films. I know that's not the case in other countries. Everything that's happening now [in the US] is healthy because it's creating debate and discussion. When you start to discuss it you start to heal and find solutions. I think in a few years -- I'm optimistic that we won't talking about this problem anymore.

You mentioned school. How early did you know you wanted to be a filmmaker?

I was 12 or 13 when I said 'This is what I want to do in life.' I grew up in Lebanon during the war and growing up during war creates a reality that is limiting. We spent some much time in shelters, and behind sandbags. We couldn't go outside to play and didn't really have a childhood. When we had power -- most of the time we didn't -- TV became very important. I was also living above a video rental store. We would sneak behind the sandbags and go there and choose films. We'd watch the same films over and over until we wore the tapes out. Cinema became a very important escape from the boredom of my childhood and the reality that I was living. I decided very early to be a filmmaker and tell stories with images and all of that.

You're not just a director but an actress.

I enjoy being an actor because it allows me to experiment with my other natures. I think it's the only place where it's legal for you to be someone else. Otherwise you're crazy or you go to jail. [Laughs] In each one of us there are multiple natures. People expect us to be a certain way and we tend to box ourselves in. That's why I like acting.

Do you think it helps you direct actors?

Definitely. I understand what actors expect from a director. It helps in both ways, directing and acting.

Your segment in the omnibus film Rio, I Love You had a child star. Did this inspire you to do that again with Capernaum or was that already the plan?

It was already on my mind because [in Lebanon] you see children everywhere suffering. The refugee crisis has been very difficult. We've hosted over a million refugees and we're facing big economic problems. The result is that you see lots of people on the street. Also knowing the power of cinema, it sort of felt like it was my duty to use my tool, which is filmmaking, to shed light on this story. Every time I saw a child standing in front of my car or on the sidewalk, trying to survive...

I'm sure it feels overwhelming.

You don't know how to deal with it so you just ignore it. The problem is too big. You don't know where to start. It's only normal to keep driving. But I kept thinking "what does it feel like for them?" I didn't want to imagine how they felt, I wanted to find out. So the research started.

Was the screenplay improvised on set given the children?

It was written in parallel with the research. We would go to the most unfortunate places, talk to the children and parents and find social workers who could take us there. I spent hours in court observing to see where the system was working or failing. So many children are in prisons or centers. The film, to its smallest details, is a result of those observations.

Once you were shooting, did you have to change a lot because you were working with children?

They are not actors at the service of what I had written. It's the other way around. I never asked them to act. I just asked them to be. I would give them the situation. It was a thin line and a negotiation between who they are and their reality and the way they express themselves and what was written. I enjoyed being open and free and embraced what life gave even though we had a solid script. The script was my core but I wasn't afraid to go away from what was planned.

Zain Al Rafeea gives one of the greatest child performances I've ever seen. He seems simultaneously very young and very old.

He has the wisdom of children who grew up on the streets. He has seen a lot.

That scene where he says 'Your words have stabbed me in the heart.' That just killed me. Did the actors -- did they think of it as playing? It's tough material and I'm sure people are worried about children being exploited in these situations.

They were being exploited in life. Zain had to struggle every day with abuse and mistreatment and fights just to prove he exists.

I can tell you something for sure: the shoot was actually their safe haven. He really enjoyed the process. Some scenes were difficult. Some took days but he felt like he was on a mission, that he was the voice of voiceless kids. He enjoyed pushing himself to cry or to experiment with conveying different emotions. It was rewarding for all of us. The cast were completely aware of their own voices. Outside the shoot nobody listens to what they have to say. But now, not only the crew is fascinated but they're able to stand in front of a real judge and express themselves.

And that's not the case in real life. Kawsar who plays Zain's mother in the film -- until now she's not been able to register her children who are now 18 and 9 years old. She was able to express herself in front of judges. 'Your system is failing. You don't know what it feels to be in my shoes.' It was a moment of victory for her.

accepting the jury prize at Cannes with her star

accepting the jury prize at Cannes with her star

When did Zain first see the movie?

In Cannes.

How did he react to the madness of that festival? It's on the world stage after all.

He was moved but he's a very tough and proud boy and nothing really shakes him. He's a wild child. The only surprise for him was the applause. And to feel all of a sudden so much love and appreciation from everyone. He felt important all of a sudden.

I know the crisis is an ongoing discussion in Lebanon but has Capernaum stirred it up even more at home?

Absoutely. It's a big conversation and debate. What we're trying to do is organize screenings for the government and try and see what can be done. I truly believe that we can be lucky and find a few people who have humanity and are willing to work to make changes.

Related

More on the Foreign Film Oscar race

More interviews

More on foreign film coverage in general