by Timothy Brayton

Coraline, which opened in theaters ten years ago today, was groundbreaking in all sorts of ways. It was the first feature made by Laika, soon to become a cultishly loved, critically praised animation studio with an Oscar nomination for every one of its four films (a fifth, Missing Link, is set to open in April). It was one of the first films in the most recent 3D fad to demonstrate a real sense of the emotional and narrative possibilities of using stereoscopic effects, and it was only rarely equaled in the years following. It represents an extraordinary leap into a brand new mixed-media animation style that I refrain from calling "revolutionary" only because nobody else but Laika seems to be interested in experimenting with it.

Coraline, which opened in theaters ten years ago today, was groundbreaking in all sorts of ways. It was the first feature made by Laika, soon to become a cultishly loved, critically praised animation studio with an Oscar nomination for every one of its four films (a fifth, Missing Link, is set to open in April). It was one of the first films in the most recent 3D fad to demonstrate a real sense of the emotional and narrative possibilities of using stereoscopic effects, and it was only rarely equaled in the years following. It represents an extraordinary leap into a brand new mixed-media animation style that I refrain from calling "revolutionary" only because nobody else but Laika seems to be interested in experimenting with it.

The truly special thing about Coraline is not that it achieved any of these things. Plenty of films invent new stuff. What's special – downright miraculous, even – is that Coraline feels just as fresh and bold in 2019 as it did in 2009...

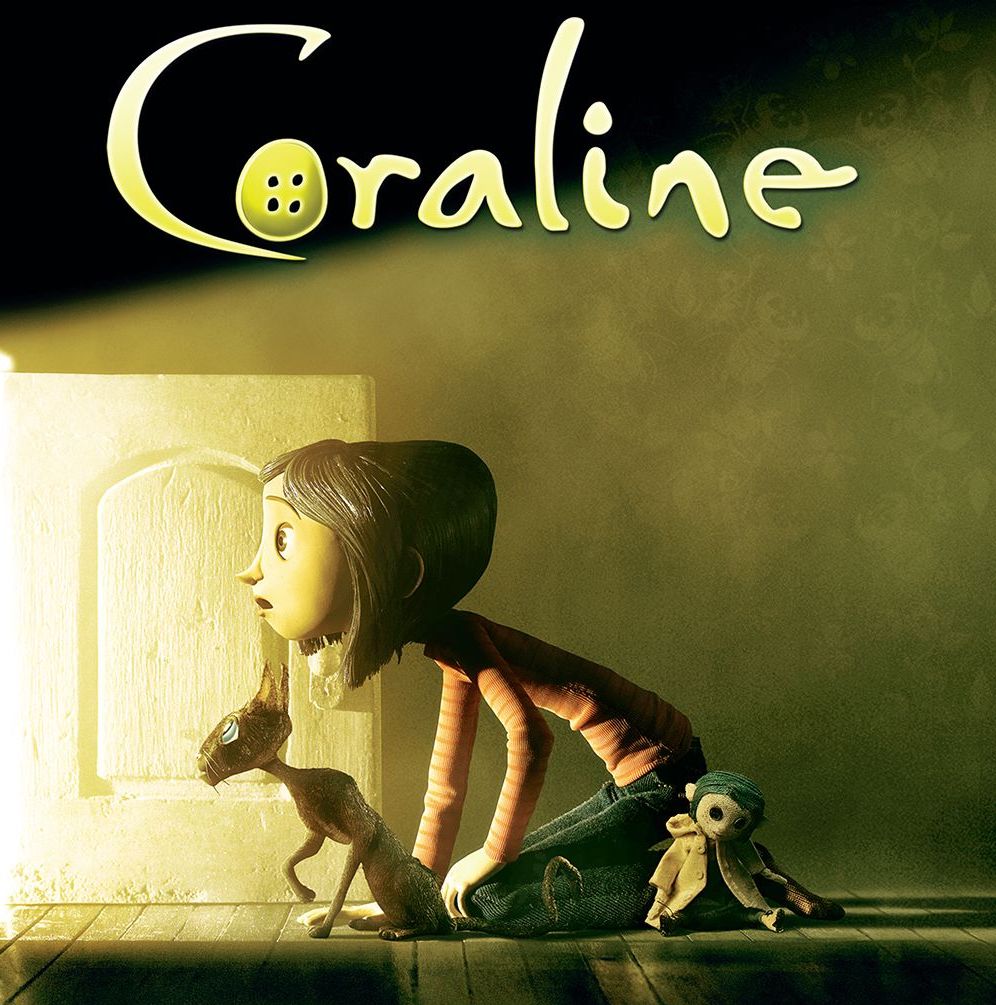

Nobody, not even Laika themselves, saw fit to try to recapture the unique essence of the thing, which is what happens when the studio's technological advances met the mind of director Henry Selick, adapting Neil Gaiman's children's book. Selick, we can presume, brought to the table the omnipresent feeling of horror movie gloom: Coraline is a creepy-looking movie, with a creepy plot in which Coraline Jones (voiced by Dakota Fanning) finds a magical porthole that leads to an alternate dimension of perpetual night and strange humans with buttons sewn over their eyes. The film is bedecked in greys and browns in the "real world", unnaturally sharp, bright teals in the fantasy world, and the whole thing looks decaying and slightly nightmarish. Nightmares that a child could watch, but nightmares nonetheless.

That abiding sense of fairy tale horror is perhaps what primarily continues to set Coraline apart from virtually any other animated feature of the last ten years. Aesthetically, after all, it's basically doing what the other Laika films have done, only it doesn't do it as aggressively. This was the film where 3D-printed faces were debuted, as well as the studio's well-publicized craftsmanship for things like clothing for the animation puppets and highly detailed, sprawiing sets. Much less well-publicized, it's also where the studio began creating its distinctive hybrid form of hand-made stop-motion animation with computer-generated effects and smoothness: as impressive as the traditional technique here undoubtedly is, Coraline is a film that relies on digital techniques to look as good as it does, or to carry off some of its most dazzling effects (such as the way the world suddenly builds itself out of a white void late in the film.

It sounds like hyperbole, but it's merely accurate to point out that Coraline was doing multiple things that no movie ever had. The fact that every subsequent Laika film has been more complex affects it only a little: astonishing, radical technique is one thing, but what gets done with that technique is another thing altogether. And the world that Selick and his impressively small team of animators and technicians put together using their amazing, unprecedented toolkit is absolutely stunning. It's moody and scarily atmospheric, yes, but also full of untamed, uncontainable characters, lively and literally colorful. It's not at all afraid of elaborate, visually busy spectacle, luxuriating in the capacity of animation to make impossible things come to life – a mouse circus, vampire bat terriers, a giant spider-web designed to look so abstract in its graphic design that it almost doesn't register – while also exploiting the great physical presence and texture of stop-motion.

It sounds like hyperbole, but it's merely accurate to point out that Coraline was doing multiple things that no movie ever had. The fact that every subsequent Laika film has been more complex affects it only a little: astonishing, radical technique is one thing, but what gets done with that technique is another thing altogether. And the world that Selick and his impressively small team of animators and technicians put together using their amazing, unprecedented toolkit is absolutely stunning. It's moody and scarily atmospheric, yes, but also full of untamed, uncontainable characters, lively and literally colorful. It's not at all afraid of elaborate, visually busy spectacle, luxuriating in the capacity of animation to make impossible things come to life – a mouse circus, vampire bat terriers, a giant spider-web designed to look so abstract in its graphic design that it almost doesn't register – while also exploiting the great physical presence and texture of stop-motion.

Put them together, and Coraline a damp, chilly movie, but also an intoxicatingly magical and visuallly seductive one. It's a perfect place to set a fantasy/horror hybrid, with much more of an ethereal, otherworldly feeling than any of its admirable successors. On top of which, it's got a strong story about the awkwardness of late childhood giving way to early adolescence, with all the narcissism, self-pity, and self-doubt that entails treated with utmost sympathy by the filmmakers and in Fanning's enjoyably sharp-tongued performance. In every possible way, the film holds up: the march of technology hasn't blunted the beauty of its visuals even a bit, and the richness of the story, more a fable than anything else, feels thoroughly timeless as a result. It already seemed at the time that Coraline was something special, and an instant classic; how good it is of history to have borne that out.