by Juan Carlos

2020 is the year that altered the face of cinema as we know it. After cinemas closed all over the world, films were either delayed or released in modified platforms like virtual cinemas and VOD. Indoor gathering restrictions also led to a resurgence of drive-in theaters. Meanwhile, streaming became an even more vital way for films to reach audiences. Platforms like Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu all have Oscar contenders this season.

2020 is the year that altered the face of cinema as we know it. After cinemas closed all over the world, films were either delayed or released in modified platforms like virtual cinemas and VOD. Indoor gathering restrictions also led to a resurgence of drive-in theaters. Meanwhile, streaming became an even more vital way for films to reach audiences. Platforms like Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu all have Oscar contenders this season.

This shift in movie-watching was further validated by the Academy’s decision earlier this year to allow films released via streaming and VOD to be eligible for the Academy Awards, provided that they were previously intended for theatrical release and that they will be available in the Academy Screening Room. This amendment to the eligibility rules is major, especially given the Academy’s previous adherence to the traditional definition of what a “theatrical film” is. Pre-COVID eligibility rules state that...

“[A] film be shown in a commercial motion picture theater in Los Angeles County for a theatrical qualifying run of at least seven consecutive days, during which period screenings must occur at least three times daily.”

That is the barest minimum that makes a film eligible for the Academy Awards in a given year, thus making them “cinema”. This rule gave birth to the ‘qualifying run’ strategy: films would meet this requirement, mostly in December, and then wait for the next year, presumably after nominations or even the ceremony, to reopen in theaters.

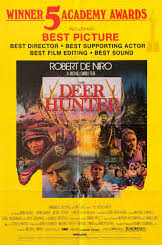

A key film in the formulation of this awards strategy was The Deer Hunter: it had a qualifying run on December 8th, 1978. It only went to wide release on February 23, 1979, three days after Oscar nominations were announced. That soon became a normal strategy.

A key film in the formulation of this awards strategy was The Deer Hunter: it had a qualifying run on December 8th, 1978. It only went to wide release on February 23, 1979, three days after Oscar nominations were announced. That soon became a normal strategy.

The bare minimum release rule has also been exploited by Netflix for its awards contenders. Because the Academy only disqualifies films that were released in non-theatrical platforms before a theatrical release, Netflix gets a pass for releasing their films on streaming and in qualifying run on the same day, something that the Academy rules explicitly stipulate is still in compliance with the eligibility rules, making them qualified to be considered as “theatrical films”.

This has been used by streaming services to separate their Oscar contenders from their Emmy contenders. Here are a few examples:

NETFLIX

Mudbound (2017): Premiered in Sundance. Released on Netflix and qualifying run on the same day. Qualifies for the Oscars and gets four nominations.

American Son (2019): Premiered in Toronto. Released on Netflix but no qualifying run. Qualifies for the Emmys and gets a nomination.

AMAZON PRIME

The Aeronauts (2019): Premiered in Telluride. Released on Prime and qualifying run in December. Qualifies for the Oscars.

Troop Zero (2019): Premiered in Sundance. Release on Prime but no qualifying run. Qualifies for the Emmys.

The current blurred line between theatrical films and TV movies is not a new problem.

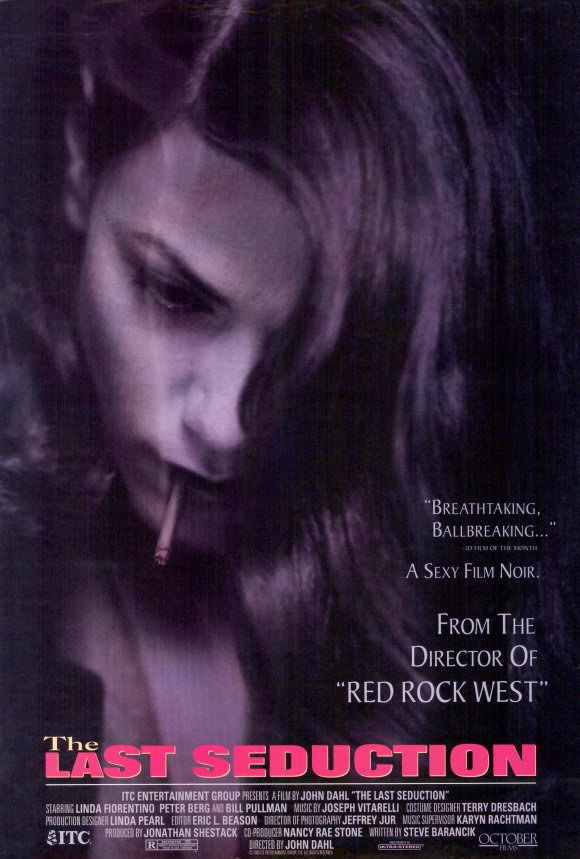

These same eligibility rules also disqualified buzzy contenders throughout the years. One famous example was the neo noir The Last Seduction (1994). Originally intended to be a theatrical film, it was bought by HBO and premiered on television four months before its theatrical release. That resulted in its disqualification for the Oscars. Best Live Action Short Film nominee Tuba Atlantic (2011) had its Oscar nomination rescinded when the Academy found out that it premiered on television before its qualifying run.

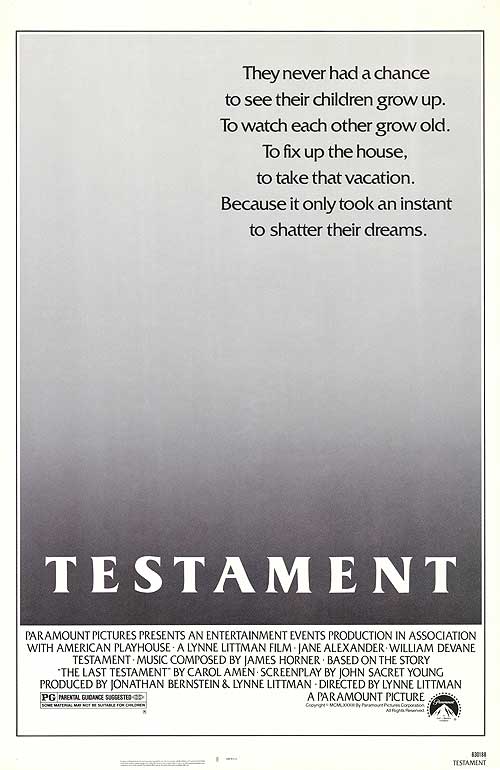

Conversely, productions that were initially intended to be “TV movies” but had a qualifying run became eligible to the Oscars. As a New York Times article articulated in 1995, films like Testament (1983), El Norte (1984), and Stand and Deliver (1988) were made for television release but were given their theatrical releases. All three earned Oscar nominations.

In between, there were films that almost did not qualify for the Oscars because of their release plans. Monster (2003) was hours away from signing a straight-to-video deal before it was picked up for theatrical release. Slumdog Millionaire (2008) almost went the same route. Both went on to win major Oscars, Best Actress and Best Picture respectively.

And then there are films that are a weird mixture of the two, dependent only on geography. The biopics Behind the Candelabra (2013) and Grace of Monaco (2014) both premiered at the Cannes film festival and were released in cinemas outside of the United States. Candelabra was nominated for five BAFTAs. However, both were considered television productions in the US and received Emmy nominations.

The delineation between a “theatrical film” and a “TV movie” is practically impossible to see now due to the widespread closure of cinemas. Even with the Academy's modified definitions for this particular awards season, several productions have challenged perceptions:

-

Bad Education premiered in Toronto last year, but was picked up by HBO and broadcasted in cable television as well as its streaming services. It was nominatd at the Emmys. However, several critics still list this as part of their best films of the year.

-

The filmed stage show Hamilton was originally intended for a theatrical release, but was instead released on Disney+. However, it will not be eligible for the Oscars but for the Emmys.

-

Steve McQueen's Small Axe anthology, consisting of five features, had its individual installments premiere in film festivals. However, they are not eligible for the Oscars but for the Emmys. They will not be campaigned as individual TV Movies but as an anthology series that will be eligible in the newly renamed Outstanding Limited or Anthology Series. Nevertheless, several critics have already included individual parts of the anthology in their best films of the year lists.

-

Let Them All Talk just arrived on HBO Max but it will qualify for the Oscars but since it was always an HBO project wasn't it always intended for TV?

-

Greyhound was originally slated to be theatrically released by Sony. However, it was then sold to Apple TV+ and was released in July. It is now campaigning for the Oscars.

-

Uncle Frank and Sylvie’s Love were both picked up by Amazon after their Sundance premieres in January and were both touted as possible Oscar contenders. However, now both films will be considered TV movies and eligible only at th Emmys.

Given these examples (and more) it's now fairly clear that the only thing that separates a "theatrical film" from a "TV movie" is awards strategy. The Film Experience will be following how eligibility is determined by the various Academies. But for me personally I admit that I cannot see a clear way to separate a theatrical film and a television film, in our COVID-stricken world. Frankly, we might just have to live with that awards-strategy only difference for now.