This week, in advance of the Oscars, Nick Davis is looking back at the Academy races of 20 years ago, spotlighting movies he’d never seen and what they teach us about those categories, then and now.

The Blair Witch Project

The Blair Witch Project

When I taught my Winter 2017 seminar about the movies of 1999, to a classroom of first-year college students who were all born in the last two years of the millennium, one of the trickiest ideas to historicize was how decisively the visibility and cultural stature of documentary cinema has shifted over the last 20 years. Compared to the decades when I grew up, nonfiction cinema has reached much further outside a relatively niche audience who tracked that filmmaking tradition. The explanations are too numerous to get into here, though they include all of the following: cheaper and more numerous technologies for recording and assembling footage; proliferating platforms for distributing and watching nonfiction films, especially in the era of the internet and of exploding cable-TV offerings; and some epochal, admittedly eclectic success stories in the commercial market, from The Thin Blue Line to Hoop Dreams to Fahrenheit 9/11 to March of the Penguins, that inspired more students and artist to pursue documentary tracks and more institutions to finance, release, and program the work.

More abstractly, I would add to that list a specifically millennial, post-postmodernist erosion of all faith in objective “reality,” differently crystallized in such landmark films of 1999 as The Matrix, eXistenZ, Eyes Wide Shut, and Fight Club. That erosion produces both a resistant hunger for whatever “real” images and stories might yet survive and its dialectical opposite: a contagious discovery, dismaying but darkly energizing, that even vérité images are subjective, manipulated, and at some level “fake”...

The easiest way to open these discussions in my course was to show a few minutes of The Blair Witch Project and ask students to imagine what prevailing image economies and cultural conditions would have to be in place for this film (and the diabolically clever assertions of its marketing) to convince so many audiences that they might be real. Of course, not everyone in 1999 fell for that conceit, but in my experience, people are awfully defensive about admitting how many of us were at least briefly duped, or couldn’t help wondering. I was impressed that my students could compile such a quick list of the giveaways that Blair Witch had to be a hoax, and even more so that they are not so saturated by ironic distance to resist being scared. As one of them stated, “I don’t buy a second of this, but could you please turn it off, because it’s seriously freaking me out.”

Filmmakers have produced brilliant and copious nonfiction films since the medium came into being, and they have spiked in prominence and artistic achievement during several periods, in many places. Again, I don’t want to feed into some stupid, linear narrative of cinema’s constant progress toward perfecting itself. Let’s limit our frame of analysis, then, to theatrically distributed documentary features in the U.S., and then narrow it further to the kinds of films trumpeted by the Academy as standard-bearers within that genus. Within those confines, the ambition and sophistication of what Oscar has honored lately and what he submitted for public adulation circa 1999 is an almost night-and-day difference.

Granted, almost any set of five films would pale by comparison to this year’s astoundingly accomplished contenders for the Best Documentary Feature Oscar (on which, see more below). And to be fairer still, the movies short-listed in the same category twenty years ago are engaging pieces of work with plenty to recommend them. But beyond being more prepossessing at the levels of form and style, and addressed to more urgent topics, the nominated movies from 2019 all anticipate a shrewder, more demanding viewer than what I discovered by renting the four movies I hadn’t seen from the corresponding race at the 72nd Oscars.

Spotlight Movies: The Documentary Feature Nominees of 1999

As much as anything, I hoped to uncover at least one nominee I could straightforwardly champion as superior to that year’s winner, Kevin Macdonald’s One Day in September, a re-telling of the hostage crisis at the 1972 Munich Olympics through the tropes of the stomach-churning, soul-sickening police thriller. I reviewed that film at length 15 years ago and did not rewatch it for this article. I did re-read my own piece, and though I may have gone in hard on this technically accomplished and frequently moving film, I still think it’s not nearly probing enough in its analysis of what transpired. The styling of the film as a propulsive thriller does distinguish it, I can now see, from the relatively rudimentary construction of other movies on the nomination list, but for reasons I try to articulate in the review, I don’t think it’s right to take this sort of slick assembly as a good in itself. Macdonald has had a curious post-Oscar career, drawing good-sized audiences to his subsequent documentaries Touching the Void (a mountain-climbing suspenser I also found overrated) and Whitney (a study of the late Whitney Houston which, ironically, I responded to much better than many other critics and fans). His first scripted film, The Last King of Scotland, earned an Oscar for Forest Whitaker and drew an equally great performance from relative newcomer James McAvoy, though I questioned some of its storytelling tactics, too. Later Macdonald features have followed a weirdly similar script of attracting major stars (Russell Crowe, Channing Tatum, Saoirse Ronan, Jude Law), distinguished crews, substantial budgets, and advance buzz and then seeming to drop off the planet. Not sure what the story is there, but I do like his US remake of State of Play.

Even if it’s not fully to my taste, the subject matter, production values, and audience-baiting construction of One Day in September would make it an unsurprising winner, except that it defeated a seemingly unstoppable force. Wim Wenders’s Buena Vista Social Club was the unquestioned documentary sensation of its release year, earning a hefty $7 million at U.S. box offices and most of the important pre-Oscar prizes, including from the New York Film Critics, the LA Film Critics, and the National Society of Film Critics. The soundtrack album, which was actually the two-year-old basis for the movie itself, went platinum for an eighth time before Buena Vista finally rolled out of cinemas, and the movie’s reputation has remained pretty hardy, as marked by its entry into the Criterion Collection a few years ago. How often do Oscar voters turn away from huge commercial hits, equally embraced by bougie and bohemian audiences, flaunting enchanting music by prodigious performers, and graced as well with colorful location photography? Wenders, nominated three times for his documentaries (and never once for his scripted features), couldn’t be blamed for arriving at the auditorium that night expecting a trophy in his hand.

To be honest, I’m not the person to trust about music-based documentaries, since they often strike me as leaning really hard on song and performance at the expense of fresh or incisive storytelling. Having finally caught up with Buena Vista, I of course admire the performers and appreciate the work of jubilant cultural recovery, even if Wenders is mostly signal-boosting what producer-performer Ry Cooder already accomplished with the preceding album. As a film, I’m not sure Buena Vista Social Club wraps its head around a few important questions: for example, how to showcase the sights and sounds of Cuba without seeming touristic or appropriative, or how to keep clichés about “timelessness” or the “soul of a nation” at bay. If anything, Wenders goes out of his way to make clear that Buena Vista Social Club intends to be a party, a love-letter, and a jam session, delaying basic information about how Cooder convened these greats and where exactly we’re seeing them perform until two-thirds of the way into the movie. To me, Buena Vista Social Club is likable and sensuously appealing, full of such charismatic presences as singers Ibrahim Ferrer and Omara Portuondo and lute player Barbarito Torres, who can pluck his instrument perfectly even while reaching for it behind his back. I’m not sure it’s a great documentary, and I certainly think Wenders’s later film Pina (which I just wrote about) makes a more organized, persuasive, and formally adventurous case for its subject’s genius. If you really want to understand the musical and cultural context for what you’re watching, and bring some of the mythology Wenders and Cooder inflate back down to human size, I strongly recommend Joshua Jelly-Schapiro’s great liner-notes essay in the Criterion Blu-ray. (Stream Buena Vista Social Club on Amazon, Google Play, iTunes, or YouTube.)

AMPAS had no shortage of well-buzzed musical documentaries to sample in 1999, and though I’m typically skeptical about “vote-splitting” rhetoric, I do wonder if One Day in September might have been helped to its victory by the plethora of other contenders reaching for a similar audience. Roko and Adrian Belic’s Genghis Blues was no Buena Vista-level juggernaut; I can’t stress enough how few documentaries are or were, especially 20 years ago. Still, it reaped hugely enthusiastic reviews at Sundance that year and grossed nearly half a million dollars in U.S. release. The movie’s principal subject is the central Asian tradition of harmonic throat-singing, as developed in Tuva, a small republic just north of Mongolia. Tuvan throat-singers can sound two or more notes at the same time, all of which exceed in range and differ in sound from what most other singing traditions around the world allow. Like Cuban son, Tuvan throat-singing enjoyed a big, trendy bounce in the late 1990s; real ones will remember when the perpetually underrated Joan Osborne headed out to the Asian steppes to study it. Genghis Blues’s entryway into this musical tradition and its larger cultural context is a blind U.S.-based jazz and blues guitarist named Paul Pena, a longtime associate of major acts from T-Bone Walker to the Grateful Dead to Bonnie Raitt. Pena, picking up the sounds of throat-singing on his home radio in the States, became a semi-expert practitioner and hooked up with some fellow American enthusiasts of Tuvan culture to visit the country (technically subsumed under Russian governance), to meet his singing heroes, and to participate in a local competition.

The Belic Brothers admit early in Genghis Blues that they barely feel qualified to make a proper, polished movie, and indeed the film is pretty crude in the visual department, at least by Oscar’s usual standards. More practiced, sophisticated documentarians might also have wrestled more deeply with the competing strands in this story: the way Tuvan hosts and American guests keep idealizing and exoticizing each other; the way Pena’s disability and his mental-health travails complicate his access to his hosts’ eager hospitality, or to his own enjoyment; the way Pena gets positioned on stage as something between a virtuoso and a novelty act; and the way that same blur characterizes the way Americans view throat-singing, as both a deeply ingrained cultural practice and some cool shit to teach yourself to do. The movie, at least, makes enough gestures in all these directions to feel like more than just a home movie of a really unique trip. Paul is such an engaging, honest subject that he holds Genghis Blues aloft, even when its structure or its motivating inquiries feel a bit thin. If your main interest in documentaries is to behold geographic worlds you’d never otherwise experience, or to encounter individuals with rich, distinctive, and complicated lives, Genghis Blues is a worthy rental.

Fun side note: the DVD includes an interview with the Chicago-born directors who recall growing up making amateur movies in their backyard with their neighborhood buddy Chris Nolan… and though Genghis Blues opened too early for that name to mean anything to anybody, further research reveals that, yes, it was that Chris Nolan. (Stream Genghis Blues on Amazon or iTunes.)

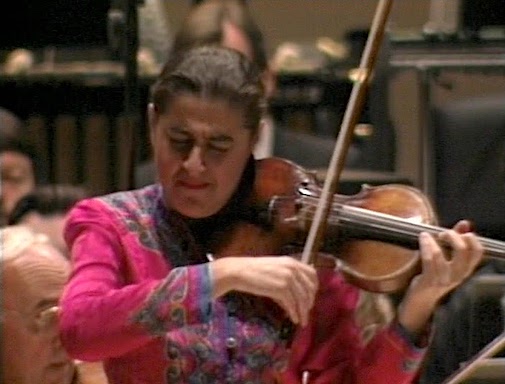

Speaking in Strings: Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg, the debut feature of documentarian Paola di Florio, continues the category’s deep investigation into music, offering a richer, more complex biographical sketch than Buena Vista Social Club or even Genghis Blues provides, while adhering to a musical tradition that’s likely better-known to the movie’s principal audience. I doubt this 73-minute feature would be nominated today, given its essential conformity to an “artist biography” template that has been abundantly reiterated before and after. Still, I would recommend the movie as a gripping and sympathetic portrait of a female prodigy in a male-dominated artistic tradition. For reasons that can’t be fully extricated from gender politics, violinist Salerno-Sonnenberg was simultaneously celebrated and denounced in the early years of her career for her emotionally ecstatic, deeply personal renderings of canonical music. Her face is almost as dramatic to behold as her instrument is to listen to, and both she and her mother chuckle at early tutors’ vain attempts to get Salerno-Sonnenberg to stand still on stage while she played. She made further waves, for better and worse, with her adventurous curation of recording opportunities, alternating the usual legends (Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev, Brahms, Bolcom, Sibelius) with, for example, a full-length re-recording and re-interpretation of the entire score for Humoresque, the 1946 Warner Bros. classic about the doomed affair between a promising violinist from a poor background (John Garfield) and his infatuated patron (Joan Crawford).

We glean early on that Salerno-Sonnenberg’s life has had its fair share of ups and downs, but the film smartly defers full disclosure of the most extreme details until well into its runtime. When that information arrives, Speaking in Strings becomes a moving, candid account of the loneliness that can accompany great fame for a soloist, and what the mental-health consequences can be. Salerno-Sonnenberg reveals that, in a pit of despair over a breakup with a lover—gendered pronouns are studiously avoided—she shot herself, and only survived because the gun jammed. Postponing those facts means we are released from experiencing the bulk of Speaking in Strings as mere build-up to a gruesome episode, or as yet another meditation on the relation of great art and great suffering. By the same token, when we do learn these facts, including from the close friend who was in Salerno-Sonnenberg’s apartment when she tried to take her life, the documentary and its subject are much franker than most about what this moment represented and how her recovery unfolded. If you’re already suspecting a triumphant Carnegie Hall performance as the movie’s culmination, you’ve apparently seen a movie before...but Salerno-Sonneberg’s delivery of a near-impossible Shostakovich concerto, to an audience that would have known well what she overcame to be there, is all the more moving because the film restrains itself from accentuating the pathos. (Stream Speaking in Strings on Kanopy, if your local library has a subscription, or see if they have the DVD in stock.)

The final 1999 nominee for Best Documentary Feature, the Brooklyn-based boxing-gym drama On the Ropes, has not a concert stage in sight. It’s an early, collaborative effort by two filmmakers who’ve proceeded to major careers. Nanette Burstein was a much-interviewed subject at the recent Sundance Film Festival, where her four-hour study of Hillary Clinton premiered to a predictable media frenzy. She has made other distinguished nonfiction films and worked as well in episodic television, cable sports (that priceless 30 for 30 ESPN profile of Tonya Harding, which substantially informed I, Tonya), and even romantic comedy (the Drew Barrymore–Justin Long vehicle Going the Distance). Co-director Brett Morgen also worked with Burstein on the successful Robert Evans biography The Kid Stays in the Picture; was an early Oscar favorite and surprise non-nominee for his 2017 study of Jane Goodall; and made a fascinating detour into animated nonfiction with the dazzling Chicago 10. On the Ropes is less polished than most of those movies but does a more than ample job of conjuring the admittedly familiar idiom of the neighborhood gym, where owner-trainer Harry Keitt hopes to discover the next great fighter. The movie originated when Burstein was hitting this classic Bed-Stuy joint for exercise, and it profits immensely from her choice to follow three especially engaging young subjects: Noel Santiago, a struggling student and unevenly-committed boxer who snaps to attention after his long-awaited first victory in the ring; Tyrene Manson, who is raising her cousins as if they are her own children and trying to manage injury, eviction, and an addicted relative while pursuing her own dreams as a fighter; and George Walton, an out-of-nowhere prodigy whom Harry rears into a formidable talent, only to watch as other managers start circling the gym, trying to pick off his vulnerable, starry-eyed protégé.

Like Genghis Blues and Speaking in Strings, On the Ropes lacks the cinematic finesse it would probably need to contend for an Oscar in the current world, although its storytelling is heartfelt and engrossing. If the movie has a major liability, and viewers’ mileage may vary here, it’s the fact that Santiago’s and Walton’s stories map so easily onto character trajectories we’ve seen a million times, in and out of nonfiction contexts, whereas Manson’s plotline only gets richer, deeper, and more troubling. When New York police enter her family’s home with a warrant on her cousin’s father, who has sold drugs to an undercover cop, Manson herself winds up charged with possession and intent to use, all of which she vigorously denies. Her court date winds up falling just as her boxing momentum is finally amassing, and in the very week she’s scheduled to appear at the Golden Gloves competition at Madison Square Garden—the kind of opportunity that could not only make her career but bring some much-needed money into a household where she is the only caretaker and breadwinner. Much that is complex, ambiguous, and dramatic in Manson’s narrative cries out for fuller, more detailed treatment, even as On the Ropes is sometimes having to show nimble footwork to sustain tension in her fellow boxers’ stories. (Ironically, Burstein conceived the project initially as a study of female fighters, with Tyrene Manson at the center, before switching focus to the very promising Walton and the casually charismatic Santiago.) All of that said, On the Ropes has lost little of the charge it must have had in 1999 as a neighborhood portrait, an involving yarn, a social indictment, and a character study, including of trainer-manager Harry Keitt, who has his own past demons to combat. An instant hit at that year’s Sundance, it remains a classic of sports-themed documentary and the object of retrospective screenings, where its subjects still dependably appear. (Look for On the Ropes on DVD—or, if you find it streaming somewhere, share the link in the Comments!)

To reiterate, these are not the documentaries I myself would pick to illustrate the peaks of nonfiction cinema in 1999. Were I asked to do that, I’d steer people more quickly toward Chris Smith’s charming, hilarious, affectively complicated, and impressively clear-sighted American Movie; Emiko Omori’s Rabbit in the Moon, a heartbreaking, multi-layered, and detail-rich analysis of WW2-era incarceration of Japanese Americans, which I mentioned in my piece this week about Snow Falling on Cedars; and two Holocaust-related stories that could not be more stylistically or thematically different, Claude Lanzmann’s hour-long A Visitor from the Living, a sort of precursor to what took fuller form in his 2013 feature The Last of the Unjust, and Errol Morris’s waaayyyyy stranger-than-fiction tale Mr. Death: The Rise and Fall of Fred A. Leuchter, Jr., which drew less attention than other Morris standouts like Fast, Cheap & Out of Control or The Fog of War but, to me, is more provocative and accomplished than either of those.

Still, as we’ve learned a million times, Oscar’s congenital failures to elevate the very best work in a given race does not mean that its own nominees should be skimmed past. All of these movies are more interesting when considered in relation to all the others. They offer a valuable, era-specific cross-section just before a larger, more diverse, more democratized, and more lucrative market in U.S. documentary filmmaking was about to bloom in the 21st century, when basic delineations between fact and fiction would enter a disastrous tailspin in this country and in the world at large.

P.S. About this year

You’ve already heard this plenty of times on this site, but the Documentary Feature competition is amazingly strong this year—for my money, handily the most impressive race anywhere on Oscar’s ballot. My own vote would go to Feras Fayyad’s The Cave, for reasons I enumerate here, but you truly can’t go wrong with American Factory, The Edge of Democracy, For Sama, or the doubly-nominated Honeyland. Factory and Edge are available on Netflix. Honeyland is free to Hulu subscribers, just as For Sama is currently complimentary for Amazon Prime members. Both of those as well as The Cave are also available for low-cost rental at most of the usual sites: Amazon, Google Play, iTunes, YouTube, et al.