by Tony Ruggio

1920... Eerily and surprisingly, wasn't so different from 2020. A new generation had upended social norms, a deadly pandemic had spread throughout the world, and a major western democracy was in the throes of a post-war identity crisis. A country in search of a tyrant, Germany was a mere decade away from learning the name Adolf Hitler, and the nation’s artistic output reflected as such.

It’s astonishing to realize that feature films have been around for more than a hundred years, that our grandest medium of pop art has endured for so long. The cinema has persevered through war, competing technology, and economic calamity. Such questions of perseverance are ripe for discussion again in the midst of our current pandemic, one that has shuttered movie theaters around the world. A film like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, currently streaming on Criterion and now 100 years young, makes clear to us that movie-making will never go the way of the dinosaurs...

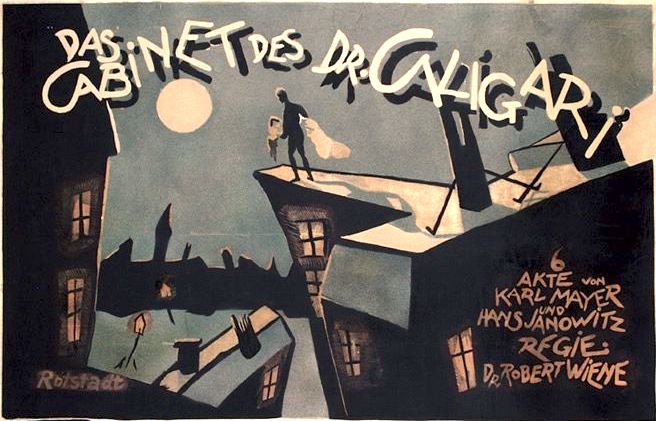

Despite the Great War and The Great Depression, film came of age in the 1920s. That was particularly true in Germany through the German Expressionist era. Defined by lavish set design, exaggerated geometric angles, and a pointed lack of realism, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari is a quintessential film of that era, one whose influence is still felt to this day in the preliminary works of Werner Herzog and Tim Burton. Director Robert Wiene crafted a tale of duality, authority, and insanity, what would become typical themes of his country’s singular movement.

Wiene was one of the very first to utilize flashbacks. Caligari opens on protagonist Francis recounting his life to another man on a park bench. The majority of the film visualizes this story, an ordeal involving one mysterious doctor, a chaotic town fair, a spectacle of somnambulism, and the strange killing spree that followed. Dr. Caligari presents to the town a somnambulist named Cesare who will answer any and all questions from a coffin-bound slumber. The scene in which Cesare “awakes” for the first time, his bugging eyes staring into the camera and into our souls, remains iconic to this day. Watching it we feel the gravity of his penetrating gaze, and suddenly become hyper-aware that we are looking into the eyes of an individual who lived a century ago.

Wiene was one of the very first to utilize flashbacks. Caligari opens on protagonist Francis recounting his life to another man on a park bench. The majority of the film visualizes this story, an ordeal involving one mysterious doctor, a chaotic town fair, a spectacle of somnambulism, and the strange killing spree that followed. Dr. Caligari presents to the town a somnambulist named Cesare who will answer any and all questions from a coffin-bound slumber. The scene in which Cesare “awakes” for the first time, his bugging eyes staring into the camera and into our souls, remains iconic to this day. Watching it we feel the gravity of his penetrating gaze, and suddenly become hyper-aware that we are looking into the eyes of an individual who lived a century ago.

The somnambulism is all a ruse, as Cesare is used by the not-so-good doctor to maim and kill the town’s denizens and abduct a young woman and “fiance” of Francis. While being chased by an angry mob, far from his master, a weakened Cesare eventually collapses and dies. As a reflection of post-war Germany, he represents the common citizen who was conditioned to kill or be killed, just as soldiers were trained when drafted into military service. By the same token, Dr. Caligari is symbolic of the German government who sent these men off to die. Early in the film, the doctor is brushed off and ridiculed by a town bureaucrat, and so the murderous rampage that ensues is potentially a makeshift rebellion, a vicious response to all of those authority figures who diminished him and his work over the years. This, all in spite of his own authoritarianism. Sound familiar?

Wiene’s film is prophetic, grappling with the notion of a country in search of an authority figure, no matter how unscrupulous, to rally behind in the aftermath of World War I. They were lost after having lost the war, devastated by the conflict and a flagging economy. With the help of fellow locals, Francis foils the twisted doctor’s plans and triumphs over the wicked doctor. The fact that the otherwise anti-authoritarian message is then undermined by a twist ending (one of the first if not the first in cinema) only serves to emphasize the psyche of the German population at that time, and their subconscious wanting for tyranny. After opposing and apprehending Dr. Caligari, the end of the frame story presents Francis as an unreliable narrator. He is a man committed to a mental institution, his stories mere ravings of a madman dreaming of escape from the asylum in which he is bound, and which is led by an asylum director resembling the fictional villain of his dreams.

The more things change, the more they stay the same. Such is the repetition of history. Wiene’s film reminds us that the tug-of-war between freedom and tyranny is never over, and neither is the question of cinema’s permanence. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari reminds us of film’s ability to thrive even under the gravest of conditions.