"The Furniture" is our series on Production Design by Daniel Walber. Click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

Safe turns 25 years old this week. I’d say it’s “more relevant than ever,” but just typing those words felt ridiculous. Todd Haynes made Safe about the way America responded to AIDS, and that’s still relevant because America has not changed. And so here we are, in another crisis of public health, watching the same phenomena play out in similar ways.

Safe turns 25 years old this week. I’d say it’s “more relevant than ever,” but just typing those words felt ridiculous. Todd Haynes made Safe about the way America responded to AIDS, and that’s still relevant because America has not changed. And so here we are, in another crisis of public health, watching the same phenomena play out in similar ways.

Let's talk about two of them. First, the way that AIDS was ignored by those who saw themselves as unaffected, even immune. Reagan could choose to do nothing because, to so many Americans, it happened to “other people.” Second, the way that its victims were blamed for their own sickness. Contracting HIV was seen as the result of a moral failure - something we’ve seen time and again, from cholera and tuberculosis to SARS and COVID-19.

25 years later, another Republican president is playing the same game. The response has been a torrent of virulent racism and an utter denial of medical reality. And once again, there is a prevailing attitude that contracting the virus is one’s own fault.

Did rewatching Safe make me feel better about any of this? Absolutely not. But it did cause me to think about a new relevance...

Carol’s (Julianne Moore) journey is primarily one of social distancing and self-isolation, something that emerges even more clearly when looking for the work of production designer David J. Bomba and art director Anthony Stabley.

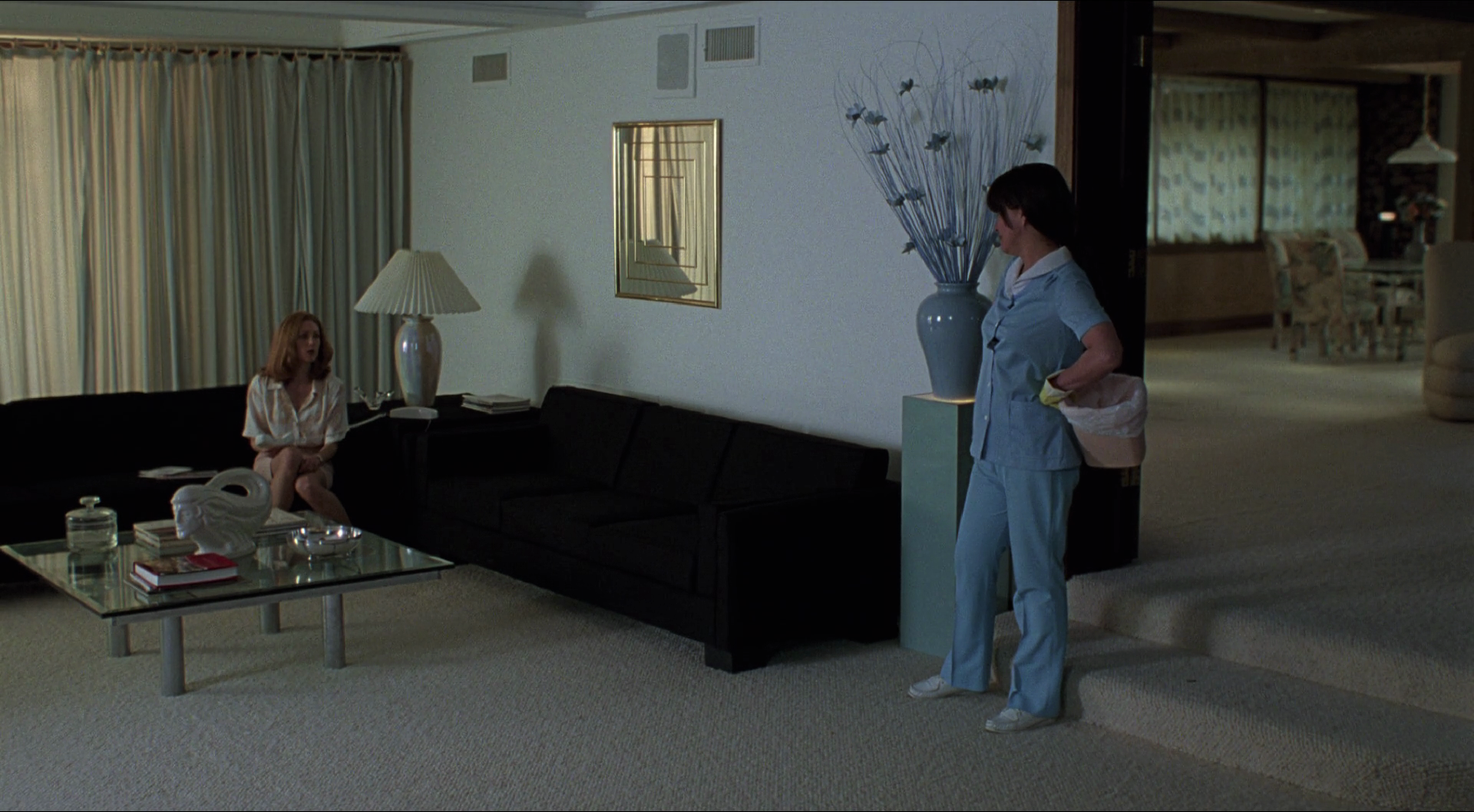

Carol is isolated by her environment even before she gets sick, in part because her house is too big.

Her primarily responsibility is managing both the thick garden outside and the modernist domestic temple within. Hence the drama when the furniture company delivers the wrong couch, black rather than teal.

This crisis tells us so much about her life, a parade of furniture catalogs and carpet swatches - all of them in the horrendous muted pastels of the age, the pinks and greens of Beaches but without even the suggestion of vitality. The bedroom is the worst.

So many lamps! Everything is mild teal or milder beige, with the occasional accent of mild purple. Those awful framed prints are a perfect touch.

That said, it’s hard to tell how much Carol cares. It’s as if she’s coloring by numbers, just matching everyone and everything else. Her friends offer a domestic blueprint rather than any actual interest or comfort, even as she grows ill. The inevitable social death knell comes at a baby shower, Carol suddenly struck ill amidst a diorama of soft colors and fluffy surfaces.

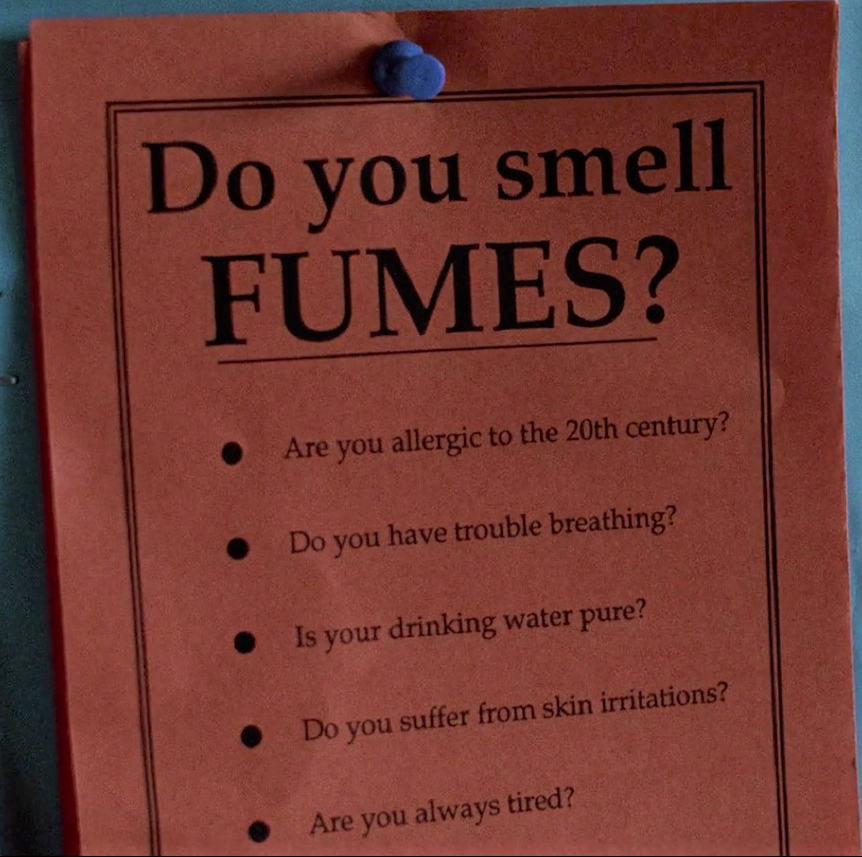

The wave of headaches, nosebleeds, and unhelpful medical professionals will send Carol looking for other answers. Eventually she will head to Wrenwood, a desert camp for the Environmentally Ill. But in the meantime, she’ll create as close to a chemical-free sanctuary as possible in her own house. While the light pink blanket fits the previous color palette, the room is mostly white. She doesn’t bother decorating.

Wrenwood won’t look like this, of course. Its cabins are rustic and nice, open to the theoretically cleaner air of the desert. Carol arrives hopeful, if tentatively so. And her first night will be challenging.

Yet one wonders if it’s really the cabin that’s the problem, or something deeper. Wrenwood is built on the charisma of its founder, who peddles a confusing theory that we make ourselves sick. The gist is that his patients have rendered their immune systems weak by not sufficiently believing in themselves. He delivers his incoherent inspirational speeches from a pulpit in a room quite clearly designed to evoke the Convention Center-like charm of a late-20th century Evangelical church.

Back in California, Carol’s friends simply chose not to see what was making her sick. Here at Wrenwood, she is expected to believe that her illness is her own fault. She did something wrong, and the only way to a cure is to find her root - to use the language of But I’m a Cheerleader, which would make quite the double bill with Safe.

But Carol doesn’t really understand what she did wrong, and no amount of spiritual word salad will make it any clearer. Instead, she slowly withdraws even further, eventually retreating into the space-age dome left by a deceased resident.

Does she make the right choice? Haynes has talked about this as a “false happy ending,” like in one of his beloved Douglas Sirk movies. Carol has finally made her way to the smallest available home, isolated from both her chemical environment and her judgmental communities. Will it work? It’s hard to feel optimistic, but it’s equally difficult to imagine an alternative.

Safe is not a manual for living in the world. It is certainly not a model for responding to COVID-19. But it does brilliantly capture some of the social and psychological consequences of a society that reacts so coldly, so foolishly and so opportunistically to the spread of disease. And it poses deeply uncomfortable questions about self-isolation, questions that go well beyond the scope of a production design column.

But I’ll ask a couple of them anyway. Is there now a Carol in all of us? How many of us will struggle to return to the outdoors in a post-COVID world, if and when we get there? (We are not, after all, in a post-AIDS world.)