Daniel Walber's series on Production Design. Click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

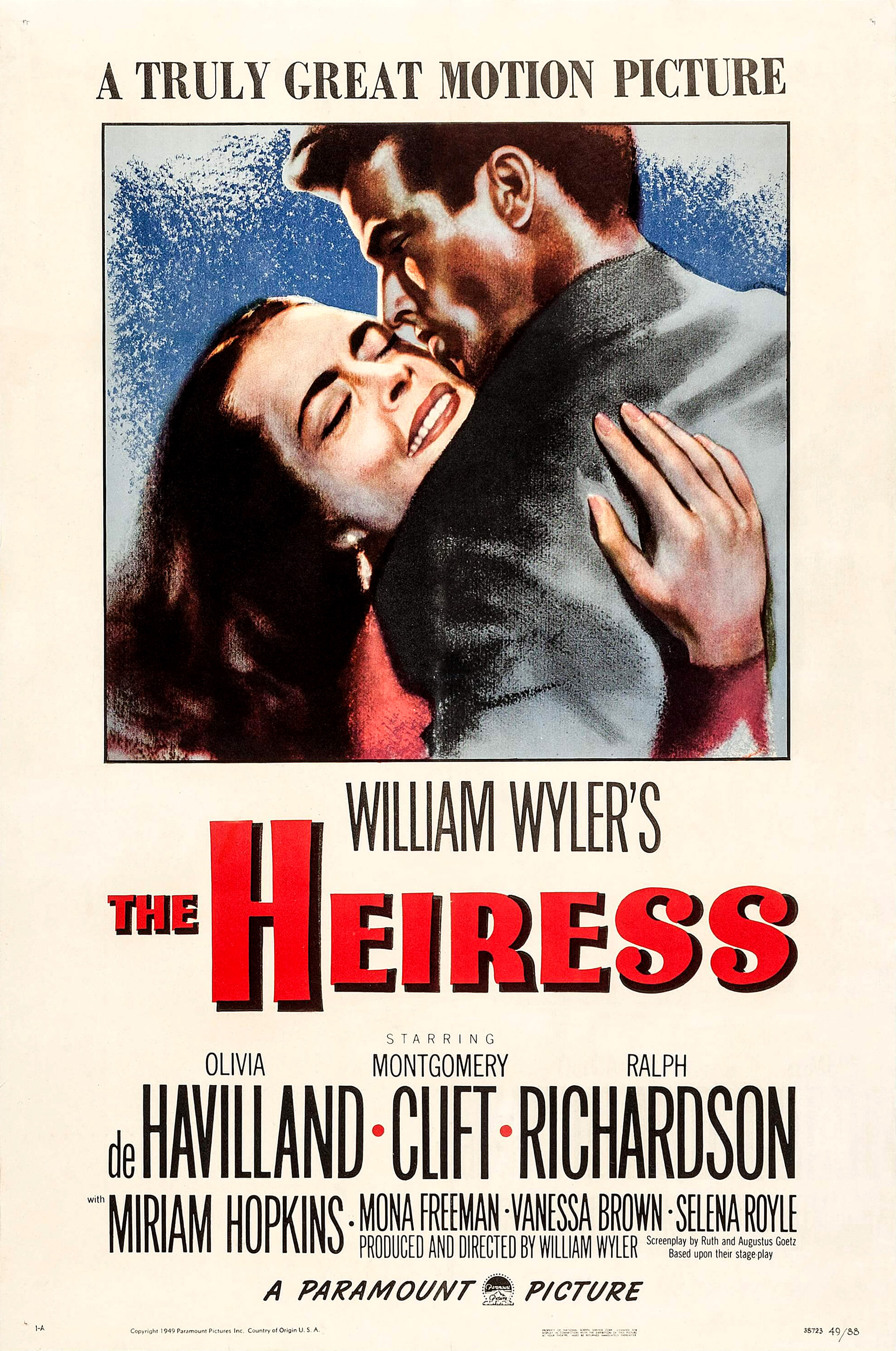

Olivia de Havilland was in nine films that were nominated for the Oscar for Best Production Design. It’s not the record, but it’s quite something. I’ve covered three of them: Hold Back the Dawn, My Cousin Rachel and Hush...Hush, Sweet Charlotte. But none of those actually won the award, so I still have some work to do. I haven’t got time for Gone with the Wind, and The Adventures of Robin Hood can wait a few weeks until our 1938 celebration, so I dove into The Heiress.

Olivia de Havilland was in nine films that were nominated for the Oscar for Best Production Design. It’s not the record, but it’s quite something. I’ve covered three of them: Hold Back the Dawn, My Cousin Rachel and Hush...Hush, Sweet Charlotte. But none of those actually won the award, so I still have some work to do. I haven’t got time for Gone with the Wind, and The Adventures of Robin Hood can wait a few weeks until our 1938 celebration, so I dove into The Heiress.

I hope you’re ready to think deeply about embroidery.

Granted, I’m not entirely sure director William Wyler was thinking deeply about his protagonist’s favorite pastime. The emphasis on Catherine Sloper’s (de Havilland) stitching can feel like little more than shorthand for “spinster” status. And the mid-19th century was a high point for this association, as embroidery was a standard part of the girls’ school curriculum.

Dr. Austin Sloper (Ralph Richardson) sent Catherine to the finest boarding schools, where she would have learned the art of the sampler from an unmarried teacher. The end of the film bluntly zooms in on one of these stitched alphabets, which in this context might as well read “OLD MAID”...

But this educational stitch is an oddly clunky gesture for a film that spends so much crafting a complex interior world, often through much more complex embroidery. The Heiress is a psychological masterpiece of the homespun, built largely from its Oscar-winning achievements: de Havilland’s brilliant performance, Edith Head and Gile Steele’s soberly detailed costumes, Aaron Copland’s austere music (which somehow manages to shine through Wyler’s ham-handed orchestrations) and, of course, the work of production designer Harry Horner, art director John Meehan and set decorator Emile Kuri.

The opening credits make this quite clear, featuring something of an embroidery storyboard. The very first image is a folk art portrait and a premonition. The flowers in the figure’s hand match those in the two identical frames above her, suggesting that Catherine embroidered them herself. Over the course of the film, she will slowly cross-stitch herself into the canvas of hers own house.

The accompanying overture introduces both Copland’s themes and the tune of “Plaisir d’amour,” the 18th century French love song that Morris (Montgomery Clift) will sing to Catherine. It’s a simple melody, one that Copland will later stitch into a tapestry of aching Americana.

We end with Washington Square, after which the original Henry James novel was titled.

The Slopers live right on the square, in a beautiful home that could very well still exist today (were it not fictional). The interior has all the patterned richness of a wealthy home of 1849, from the curtains to the upholstery. It can seem to swallow up everyone in it, especially Catherine.

It’s her father’s house, and her father has exerted so much control over her life - despite clearly despising his daughter as an inadequate replacement for her mother. And so for much of the first act, Catherine’s relationship with her surroundings is one of quiet captivity. Her most ecstatic moment of love with Morris, the night they plan to escape, comes not in the house but in the mews outside.

Later, waiting for his carriage to sweep her away, she thinks she hears him. She tosses back the lace curtains. Her black cloak is among the simplest things she wears, devoid of the stitched and patterned details that hem her in. She looks ready to step out of a tapestry.

But elopement is not in the cards for Catherine. She cannot escape the house because she is the house, something that the costumes hint at a little earlier. Arguing hopelessly with her father, her dress resembles the natural patterns of wood, suggesting she is cut from the same material as the stately settees and the sliding doors.

But it is after Morris’s abandonment that Catherine really begins the work of self-embroidery. Even her father, heretofore overbearing, quickly ails into irrelevance. She calls his bluff, tells him off, and keeps her full inheritance anyway. He dies, she wins, and she devotes her hours to needlework.

Needlework leads to redecorating. For example, many earlier scenes include this Hudson River School landscape, hanging above the couch. One wonders if Catherine cares much for the famous painters of the day, depicting vistas from which she will soon lose all interest.

After the doctor’s death, Catherine replaces the landscape with one of her floral embroideries.

And, as we can see, she’s already hard at work on another. As her floral designs become more elaborate and more prominent, she becomes further and further entrenched into her ornate, rigorously patterned home - a home which is now incontrovertibly hers.

Recent episodes of The Furniture