"The Furniture," by Daniel Walber, is our weekly series on Production Design. You can click on the images to see them in magnified detail.

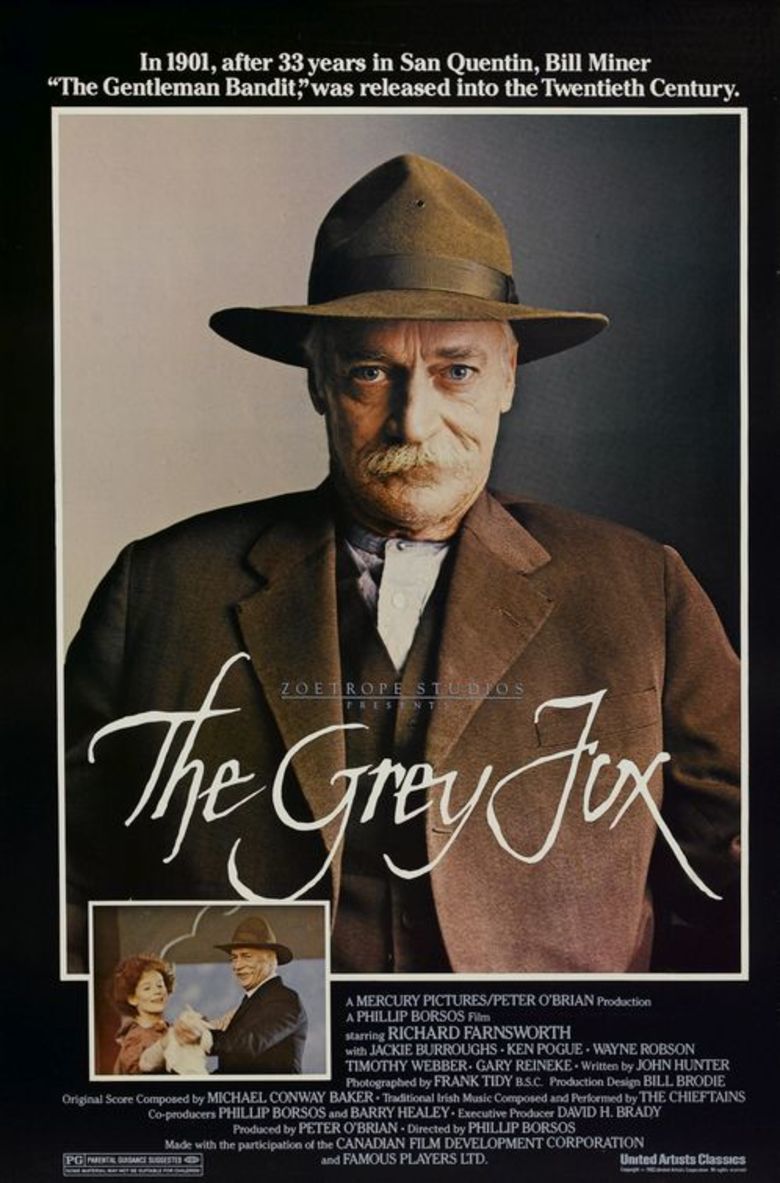

Yesterday would have been the 100th birthday of Richard Farnsworth. You might have seen some tributes on Twitter, most of them recalling Farnsworth’s Oscar-nominated performance in David Lynch’s The Straight Story - the actor’s last film. Today I’d like to turn to something earlier, a gorgeous Canadian Western called The Grey Fox.

Yesterday would have been the 100th birthday of Richard Farnsworth. You might have seen some tributes on Twitter, most of them recalling Farnsworth’s Oscar-nominated performance in David Lynch’s The Straight Story - the actor’s last film. Today I’d like to turn to something earlier, a gorgeous Canadian Western called The Grey Fox.

It’s the kind of movie that feels undiscovered even as you’re watching it - even now that it’s been beautifully restored and rereleased by Kino Lorber. It’s not that it was ignored upon release, really; Farnsworth got a Best Actor - Drama nomination at the Golden Globes and it swept the Genie Awards. But its quiet, slow, rainy charm lends it an air of the forgotten, as if it had been left on a shelf for a century.

The subject helps: the last years of the last notorious stagecoach robber in the West, released into the 20th century like a ghost...

But the real magic comes from a remarkable synchrony of vibe across crafts. Rarely do we see a lead performance so in tune with the production design around it, Farnsworth’s approach fitting perfectly into the work of production designer Bill Brodie, art director Ian Thomas and set decorator Kimberley Richardson.

Real-life bandit Bill Miner was known for his gentility. He was nicknamed the “Gentleman Robber” as well as the “Grey Fox,” and is often credited as the first to shout “Hands up!” - presumably instead of just shooting everyone in the stagecoach. The Grey Fox catches up with him in 1901, upon his release from 33 years in San Quentin Prison. We see the light catch his smile as he steps into the light of San Francisco. He then quickly heads north, to his sister’s home in Washington State.

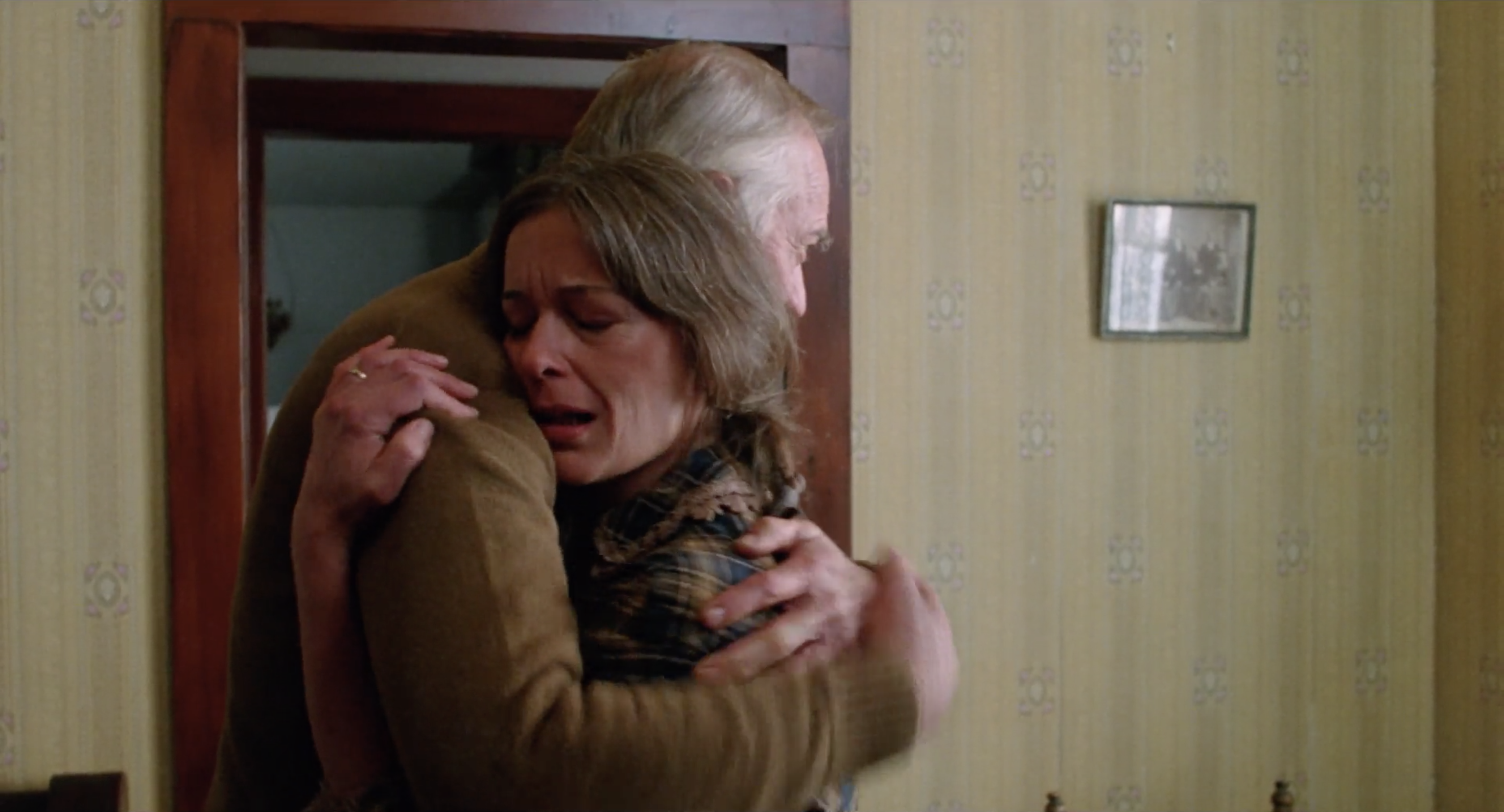

His time here is short. A screening of The Great Train Robbery rekindles his passion for the heist, and he leaves to seek his fortune. But his brief sojourn with his sister sets up two of the film’s most persistent design motifs: piles of wood, like those above, and a seemingly endless parade of similarly muted wallpapers.

And it also sets up Farnsworth’s approach to the outlaw. He’s a man of few words, but not necessarily of few emotions. He’s very careful to keep the light in his eyes during his many silences, differentiating Bill from the stereotype of the Old West gunman who is as stiff on the inside as he is on the outside. His silence comes from his wisdom, not from a caricature of stubborn masculinity. He’s like a calm rain on the evergreens, a simple pattern in warm colors on the wall. And so both of these things, wet wood and beige wallpaper, follow him wherever he goes.

Even the train robberies he commits are remarkably chill. Often waiting until the middle of the night, he keeps his cool while kindly talking with rail engineers and mail clerks. His reputation, after all, is not a violent one. He only steals from the railroad and he doesn’t kill.

Eventually he decides to lay low in Kamloops, posing as a miner in his friend’s remarkably peaceful (if not very profitable) mine. It's underground where he meets the local representative of the Royal Canadian Mountain Police, the green and gentle Sergeant Fernie (Timothy Webber).

Eventually the Sergeant will participate in Bill’s downfall, though he won’t be too thrilled about it. Catching the notorious bandit might come with a promotion, but it won’t make him any friends in Kamloops. And besides, he comes to like him.

So he’s not too thrilled to see Detective Seavy (Gary Reineke), the Pinkerton agent that has been sent into Canada to finally track down Bill. The Mountie and the mercenary meet in Fernie’s office, where the paint is chipping and the walls are covered in guns and animal bones - it’s a classic of the Old West, but it’s also colder and harsher than the film’s other interiors.

For comparison, here’s the room where Bill and co-conspirator Shorty Dunn (Wayne Robson) hide out. Cozy, no?

There’s even a bathtub, a quaint basin with a wooden rim. There’s no wallpaper, presumably because it would peel, but there’s plenty of damp wood.

My favorite interior, though, isn’t a residence. It’s the local newspaper office, where Bill encounters local photographer and rabble-rouser Kate Flynn (Jackie Burroughs). On first glance, Kate couldn't be less like the Gentleman Bandit. She speaks her mind clearly, assertively and at length. She unleashes a torrent of words at the newspaper editor, who refuses to publish a letter she’s written in support of the trade union movement.

Bill quickly takes a shine to Kate, but it’s not just because opposites attract. The production design seems to hint that they might have more in common than we think, perhaps a shared palette of values. Look at the wallpaper. It’s much busier than every other pattern in the film, to be sure, but the colors essentially match. It might be a striking variation, but it would fit right into the same house.

Subtleties like these work beautifully alongside the subtleties of Farnsworth’s performance. His quiet smirks speak volumes, his deceptively understated line deliveries imply a lifetime of wisdom and understanding. And it’s all of this together, a hushed atmosphere of mist and transience, that makes a bright moment of love in a gazebo seem like a miracle. And they make it all the more easy to believe that somehow, despite history, Bill is still peacefully hiding in the mountains of British Columbia today.

Previously on this season of The Furniture

- Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

- Babyteeth (2020)

- Barton Fink (1991)

- Battle of Neretva (1969)

- First Cow (2020)

- Frida (2002)

- The Golem (1920)

- The Heiress (1949)

- Joan of Arc (2019)

- Poseidon Adventure (1972)

- Safe (1995)

- Shirley (2020)