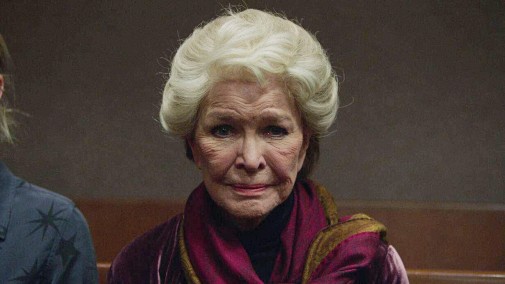

At 88 years of age, Ellen Burstyn is back on the hunt for gold and she might just become the oldest acting Oscar nominee of all-time for her work in Kornél Mundruczó's Pieces of a Woman. (The record is currently held by Christopher Plummer in All the Money in the World, who had just turned 88 at the time but Burstyn would be just a bit older). Burstyn's film, now streaming on Netflix, concerns Vanessa Kirby's Martha, a woman dealing with the unimaginable pain of having lost her newborn daughter. Burstyn plays the protagonist's mother, a severe matriarch whose disapproval of her daughter's life choices is an incandescent force, blinding in its intensity.

The actress breathes life into this supporting role, illuminating the brittleness, the scars of past woes, and the terror brought upon by the first signs of dementia. It's a showy performance, complete with an Oscar clip-ready monologue that unspools from Burstyn like a torrent of misdirected fervor. As we ponder if AMPAS will grace the thespian with another honor, let's look at her record with the Academy. Ellen Burstyn has been nominated six times and won once…

THE LAST PICTURE SHOW (1971)

An elegy for lost youth, lost Texan small towns, and lost cinema, The Last Picture Show is Peter Bogdanovich's debut feature. It's bittersweet and heartfelt, a nostalgia that's clearheaded enough to see through the rose-tinted glasses. Despite the young taking center stage, it's the older folk who delineate the tone. It's, in the end, a film about death and dying, about empty streets that are only becoming emptier as time goes by, ravaging everything it touches. It's the past preserved in crystal, then shattered, stepped on until its shards turn to silvery powder.

Ellen Burstyn's Lois Farrow was once the prettiest girl in town. When we meet her, middle-age has robbed her of past glory. The ghost of youthful sultriness still haunts her every step. Most of all, Lois is bored and Burstyn lets that suffocating sentiment inform every gesture, be it tired coquettishness or the woman's frustrated confusion when dealing with her teenage daughter. There's emotional clarity to Burstyn's work, especially when grief shows its ugly face. However, her attempts at projecting sly sauciness feel a bit forced. It's a good performance and a worthy nomination but far from the actress' best achievements.

She was beaten by her The Last Picture Show costar, Cloris Leachman. This is still the only Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination in Burstyn's career. But that might change this year.

From its desert opening to its Washington-set climax, The Exorcist is a horror classic like few others. William Friedkin's filming of William Peter Blatty's novel is a visceral nightmare. The kind that crawls under the viewer's skin, polluting their mind with ancient evils and modern anxieties misshapen as demonic facsimiles. Still, the frights of this unholy movie depend on primordial wrongness, the contamination of mundanity, the violation of innocence. In other words, you feel the human fragility and the humanity that's coming undone.

Chris MacNeil is a Hollywood star, the mother of the girl whose body becomes Pazuzu's vessel. Ellen Burstyn plays this actress with smart naturalism, underlining her mundanity before opening the gates of hell beneath her feet. The performance is an escalation of terror, helplessness eating away at a mother who can't do anything to save her beloved daughter until all that's left is a pulsing miasma of despair. It's because of her that some of the most upsetting scenes in The Exorcist are the ones with no puke and no priests, those set inside sterile hospitals where the agonized go in search of medical salvation.

But the 1973 Best Actress champion came from another Best Picture nominee. Glenda Jackson won her second Oscar for the comedy A Touch of Class.

ALICE DOESN'T LIVE HERE ANYMORE (1974)

It's a pity that Martin Scorsese doesn't make more movies centered on women. His few flicks with female leads are among his best, with Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore standing out as a wonderful example. Not that it doesn't look like a Scorsese film. Its setting and milieu may be distant from the director's usual fare, but his vision is seen throughout, especially during the opening. From Sirkian excess and robust artifice, the director cuts to 70s realism, dusty and dirty. It's a film about dashed dreams, about knowing the imperfection of reality, accepting it, learning how to live with it. A film about waking from a Technicolor dream and facing the grit of waking life.

The titular Alice is, of course, played by Ellen Burstyn. Here, she's a woman faced with unexpected widowhood, forced to travail with her son in search of a job as a lounge singer. In her path, she finds disillusions, male aggression, sisterhood, perchance love. It's quite the character arc and Burstyn performs it with amazing ease. Instead of foregrounding her craft, the actress delivers a feat of underplayed naturalism, lacing Alice's misfortunes with unexpected humor. The way she draws comedy from tragic news, how she plays with her on-screen son, and confides with Diane Ladd's Flo, all those details are both golden and worthy of gold.

1974 is a candidate for best Best Actress lineup of all-time. The truth is each of the five women would have been a good victor. Still, Burstyn reigned supreme over her competition and scored her only Academy Award. It's a glorious victory, even if she wouldn't have been my pick.

SAME TIME, NEXT YEAR (1978)

Conspicuously based on a play by Bernard Slade, Same Time, Next Year is a turgid affair whose staginess is both overwhelming and inescapable. It concerns the decades-long affair of two married people who meet by chance in a secluded inn. They first find each other during the postwar years, but their one-night stand gradually turns into a lasting relationship. Every year, they meet again in the same place, spend a night of passion, and then go on with their separate lives. As the years unfold, we see them transform into stereotypes, their lives dictated by visual gags instead of organic evolution and authentic feeling.

Pardon the harsh words, but I'm not a fan of Same Time, Next Year and can't quite fathom why AMPAS went so wild over it, bestowing the film with four nominations. The citation for Best Cinematography is superlatively baffling. Burstyn's nod is more understandable at least. Though she's unable to resolve her character's wild changes of style, values and morals, there's an attempt made. We can see her struggle trying to tie all these loose threads, weaving a warped tapestry that tells the story of a normal woman's life as seen through her annual interactions with a dear lover. Still, not even she could make the countercultural phase of this story feel real, earned, or minimally convincing.

As with 1973, Burstyn lost this Best Actress bid to another actress winning her second trophy. This time, it was Jane Fonda for her star turn in Coming Home. Burstyn did, however, tie for the Golden Globe with Maggie Smith.

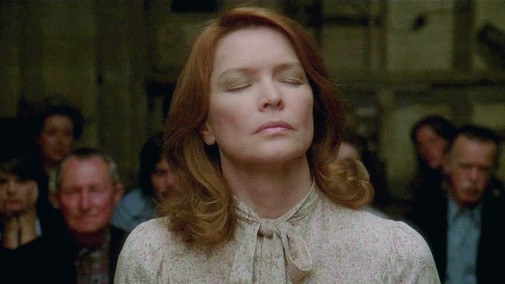

RESURRECTION (1980)

What an odd picture this is. Previously discussed in the 1980 Best Supporting Actress Smackdown, Daniel Petr's Resurrection is a proto-sci-fi drama about a woman who gains healing powers after she's part of a catastrophic car accident that results in her husband's death. It's heady defiance of genre norms, boldly refusing to deliver answers or conclusions that untangle its strangeness. The film turns its face on religion, but indulges in its imagery, spits on the face of classic melodrama but is unashamed of reveling in pure feeling devoid of narrative purpose. Overall, it's a fascinating conundrum that seldom works but is all the more interesting for it.

In the role of the unlikely healer, Burstyn is as fascinating as her film. At the start, we are in usual territory for the actress, casual naturalism grounding the early chapters in some semblance of human reality. However, it's when the narrative goes crazier that the performance truly sings. My favorite element of Burstyn's work is certainly the physicality brought to the role by its thespian, how the body manifests the cost of fantastical amelioration of other people in need. Even at the end, with a long grey wig and the tics of theatrical old age,

Nobody was going to take 1980's Best Actress Oscar away from Sissy Spacek. Her performance in Coal Miner's Daughter is the prototypical biopic star turn that sweeps the awards season.

Darren Aronofsky's sophomore feature is an ecstatic moral tale about the perfidious influence of addiction. Such a description suggests a degree of self-righteous didacticism the film doesn't necessarily exemplify, always more concerned with understanding its characters' suffering than in making them case studies. From its opening in a Coney Island summer to its wintery conclusions, Requiem for a Dream follows in line with many of Ellen Burstyn's most famous projects, detailing the cataclysm that is the implosion of personal utopias, dreams crumbling, hopes dying.

Sara Goldfarb, played by Burstyn, is perhaps the most tragic figure in this sad tale. A lonely widow whose junkie son only comes home to ask for money or steal her TV, she's consumed by lies about getting on her favorite self-help show. Going on a wretched diet aided by uppers, Sara starts losing herself to obsession, to addiction, to the need for some ineffable idea of happiness. Burstyn holds nothing back, going as big as her director does, feverishly exploding in the wreckage of human misery, her body and soul falling to pieces. It's devastating to witness, bruising, lacerating... a tour-de-force!

As great as Burstyn is in Requiem for a Dream, I'm sometimes still surprised AMPAS nominated such a weird abrasive flick. The winner that year came from a much more conventional picture, the great Erin Brockovich starring Julia Roberts.

Are you rooting for Ellen Burstyn to get a seventh nomination this year? Would you have ever given her a second win?