by Nathaniel R

Director David France and Visual Effects Supervisor Ryan Laney on "Welcome to Chechnya"

Director David France and Visual Effects Supervisor Ryan Laney on "Welcome to Chechnya"

If you haven't yet screened the documentary Welcome to Chechnya, a finalist for Best Documentary Feature, don't delay. The film details the journey of a group of incredibly brave LGBTQ activists in Russia, working to help people escape Russia and Chechnya where the government condones the abduction, torture, and murders of queer people, by denying that it's happening at all. The primary storyline involves "Grisha" (not his real name) a gay event planner who was abducted and tortured in Chechnya while working on a job there.

Due to the unique risks to the people involved and the need to protect their identities, Welcome to Chechnya opted to deploy innovative visual effects rather than the traditional "shot in shadow" or blurred faces you would usually see with anonymous voices in documentary. Now the film finds itself charting unfamiliar awards territory as a finalist for the Best Visual Effects Oscar, a category that's usually focused on sci-fi films, superheroes, and action blockbusters...

Visual effects supervisor Ryan Laney, who's worked on many such blockbusters, isn't sure he wants to go back. "I've never worked on something more important," he says with obvious emotional investment. That's where his focus will stay for the time being as his goal is to make the techniques developed for Chechnya widely available for other documentarians and journalists. The work was a major challenge as the footage wasn't shot the way HOllywood films are since they know the visual effects post-production. Laney had to work his experimental technique over low light, grainy video, shaky handheld cameras, and more. "There were nine different complications any shot could have had and a lot of them had several of them."

When we sat down to talk to Laney and Chechnya's Oscar-nominated director David France (How to Survive a Plague) we confessed that we didn't know quite how to discuss visual effects. 'Don't think of it as a visual effects film,' they offered. In fact, France hadn't when he began the project...

[This interview has been edited for length and clarity and contains spoilers.]

NATHANIEL: When you originally set out to make this how did you even know where to start. How do you make this film without endangering people?

DIRECTOR DAVID FRANCE: My first telephone call to the woman who directs the shelter, Olga Baranova, who is in the film, was conducted over an encrypted app. She explained to me how dangerous my request was, that it was probably not going to be possible to make a documentary about this issue. Because... how do you arrive with a documentary crew? How do you keep entering and leaving a secret network of safe houses? And the big question: How do you convince the people who are residing temporarily in those shelters to appear in a film?

Daunting questions.

DAVID FRANCE: She was pretty confident that I was not going to be able to get anybody to say yes. So I knew that I'd have to propose to them that there would be a way to disguise them. I've never worked in the area of VFX, nor in the area of disguises, or spy craft or anything like that. So I googled rotomation techniques. I downloaded a cute little file that just showed a little girl and a guitar. Her true image is carved out and then filtered back in as a kind of cartoon.

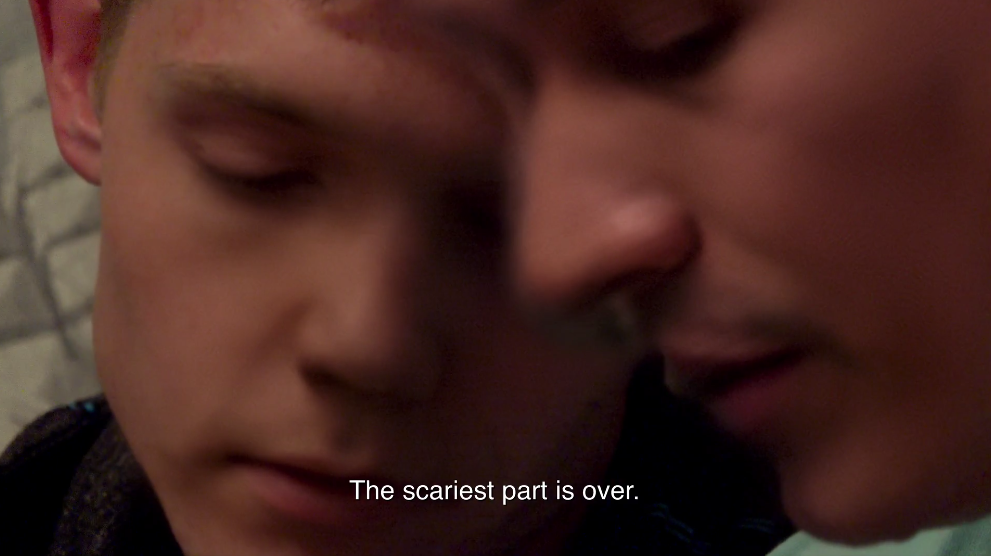

the final "veil" effect, you get so much emotion and character without revealing the real face.

the final "veil" effect, you get so much emotion and character without revealing the real face.

So that's what I brought them. I said, ‘Look, I'll do something like this, but I'll promise you that whatever I do is going to work to protect your identity, and I will return to you with the suggestion about how we'll actually do it.’ And so I started shooting. I shot for 18 months without really giving it much of another thought.

And they were okay with that without knowing what it was going to look like?! Just trusting you?

DAVID FRANCE: Absolutely. They knew that we had enacted a very complex system for security protocols around the digital files. Their entire lives were defined by security protocols. And most of them were reviewed by and signed off by David Isteev who is also in the film. With his sign off of our security protocols, people felt pretty safe that the footage itself was not going to get out. And that I wasn't going to release a film without their approval. In fact, instead of a standard appearance release we had this kind of contract that we were calling it an “informed consent form” that tied us together through the process of the whole filming so that they would have a final sign-off before the film would ever get released.

That seems very nerve-wracking from a director’s standpoint. You don’t actually know that they're going to sign off at the end. And if they don’t you don’t have a movie!

DAVID FRANCE: I was not as nervous as I should have been. Certainly Alice Henty, our producer, took on that weight. We were lucky that we were independently funded. We raised funds from the LGBTQ community who knew how important this was and gave us the money to make the film. So we didn't have the pressure of a studio saying ‘What you're doing is ridiculous!’

So Ryan, how soon did you start your work?

Ryan Laney, far left, overseeing VFX work on "Welcome to Chechnya"

Ryan Laney, far left, overseeing VFX work on "Welcome to Chechnya"

RYAN LANEY, VISUAL EFFECTS SUPERVISOR: They were pretty locked on editing. They spent a year searching for a solution before they found us. It really helped a lot starting visual effects with a locked edit. There's not a lot of things that you end up doing that get thrown away. So that helped us minimize the amount of overhead. It’s pretty unusual for VFX to start with a locked edit, but it ended up working in our favor. But It's still a labor-intensive process.

I’m about to reveal how clueless I am about how this was done. When I was watching the film I kept thinking ‘Wait, are actors recreating all these movements and expressions and then being super-imposed? How is this happening?!?' Because it doesn’t look “real” exactly -- you can tell that they’re being protected -- but the ‘fake faces' are real enough that you become sort of attached to them as 'that is what this person looks like.'

RYAN LANEY: That's fantastic to hear.

DAVID FRANCE: The genius of what Ryan has managed to do here is what amounts to a kind of a skin transplant. Everything you're watching, it looks exactly the same without the disguise: the same darting of the eyes, the same words being spoken, the same micro expressions even. What we've been able to do with this process is to allow all of that to happen, to really give these individuals back their power to tell their own story and to share their journeys. With mafia informers they used to do plastic surgery to cover the identity...

What you’re saying is they should’ve hired Ryan instead.

DAVID FRANCE: This is a like the visual effects witness protection. You called them ‘fake faces’...

RYAN LANEY: We call them “veils” to give it a name.

DAVID FRANCE: The faces you’re seeing with the veils come from real people. We recruited LGBTQ activists for the most part, many of them from an organization called ”Voices 4”. We were able to kind of cast them through their Instagram selfies, once Ryan approved 'the face fit'. We approached them like ‘Would you consider, as an act of activism, becoming a human shield to protect the lives of the people?'

Activist David Isteev, one of the few people who don't wear a visual effects "veil" in the film

Activist David Isteev, one of the few people who don't wear a visual effects "veil" in the film

That’s amazing. I want to talk about the "veil" process in a second but first, one of the things that surprised me was that the leaders of the LGBTQ center are not masked in any way. Obviously they're putting their lives at risk every day. Had they long since accepted the risk?

DAVID FRANCE: When we first started, they weren't sure that they want it to be unmasked in the film. We filmed for 18 months. During that period of time, though, it became clear that their identities were known to the authorities. By that time, as you see in the film, Olga had already been threatened to the point of needing to flee the country. And David came to the conclusion that he would be better served by appearing in the film as himself, as a way to draw attention to himself as an individual known now around the world. And that, that would…

...protect him in some way. The more visible you are, the more noticeable it is if you disappear, right?.

DAVID FRANCE: Exactly.

Given that Maxim was going to eventually out himself to the authorities as well was there ever a consideration of not putting a “veil” on him in the final film? I’m glad you did it the way you did it for what it's worth.

DAVID FRANCE: We did of course discuss it because it would have cut our time in half. What we realized was that the VFX was an actual character in our film. We wanted people to know when they saw somebody who was in mortal danger. And if we didn't cover him, it could have telegraphed to the audience that he would indeed eventually, bring his story to the public. But, in this discussion of this process, we spoke a lot about wanting to be very transparent about being not transparent if you will.

So right at the beginning of the film, we have a statement saying that these people are being digitally altered. We actually worked with Ryan to, to amplify the soft focus around their faces so that you could see who was in danger, you could see the risk for them. So it was really more about keeping that part of the story then it was about the reveal itself. We knew the reveal was going to be something to address and work on the timing of. We had a ‘locked picture’ which we unlocked once we realized what this was going to do to the way the story was told.

And the design for that reveal was Ryan's, it was really beautiful to open the face up through his eyes. He was wearing brown eyes for two thirds of the film and he suddenly has blue eyes. That kind of explosion of a new character...

It’s so beautiful. Like coming out of a cocoon.

DAVID FRANCE: And it immediately showed his vulnerability and his courage.

Ryan, how did you figure all this out? It looks amazing and that shift in the climax, the lifting of the veil. It’s one of the best moments of the whole year in cinema. It’s such great storytelling.

the climactic press conference

the climactic press conference

RYAN LANEY: David did a really great job at kind of massaging that reveal. The process to get there… we started with what David was originally looking at, which was a Scanner Darkly sort of cartoon filter effect on top of things. But in some ways that actually accentuates the things that make people unique -- especially facial shapes. We knew right away we needed to do something different.

Our first idea was based on some face research out of University of Glasgow where they do a lot of attractiveness and mating studies -- things that are completely different than what we're talking about. But they had produced this picture of faces around the world. It's really fascinating just to look at all the people that I know who fit on that graph somewhere, how similar we all are but how unique we all are at the same time. The things that make us visually unique are really subtle because the geometry is all about the same.

Yeah.

RYAN LANEY: So we thought a cartoon effect was too big of a move. What could we do in a small move to alter these faces? There's a machine learning technique called ‘style transfer,’ where you sort of look at the style of one picture and apply it to the content of another picture. And that's effectively what we're doing. We're treating eyebrows or nose shapes like brush strokes -- it’s more like a prosthetic or like a painting on of a new skin that it is a complete replacement. So it does pick up all of that subtle motion underneath that really telegraphs a person's emotions.'

These veils are something that you developed yourself in for this specific project?

RYAN LANEY: I mean, we borrow. Visual effects is always standing on the shoulders of giants so to speak. Google has a product called “TensorFlow”. That's our back end. There were a couple of papers in 2017 called semantic style transfer. There’s a guy Károly who does this seris “Two Minute Papers" and they’re really fantastic summaries of the current technology of things that are written in academic papers. In visual effects there's this tight bond between academia and production.

I had no idea.

RYAN LANEY: We're always in concert with each other. ‘Oh, we did this on a film and it works. And then, you know, a school will pick that up and, do a step on top of that. And then we’ll pick it back up and put a step on top of that. This was definitely one of those experiences where we were reading all of the available papers of the moment, trying to get an idea of how we could do this thing that was at the time impossible. We were really lucky that David didn’t know what was possible in a way.

[Laughter]

RYAN LANEY: I don’t think we would be here if anyone had been rational about this.

Well, David back to you then. You were obviously the perfect person to make this. Your most famous picture, How to Survive a Plague, is such a terrific documentary and it also does the impossible, fighting off systemic negligenc, death, and incredible odds.

DAVID FRANCE: That’s a film I think I wouldn't have started if I weren't naive. How to Survive a Plague was built almost entirely from archival footage, shot by 35 or 40 different people. And the idea that you could build together a nine year narrative arc, just employing that footage… It was only once I got into it that I realized what a ridiculous thing it was and how hard it was going to be.

It was the same with this. Ryan's work took almost a year and that was a year added to the length of this production which was for a very urgent cause that we wanted to get out to the world. But we knew we had to do it this way. It wasn't until Ryan showed us the first example of, one of the characters wearing the veils, that I knew that this was going to be possible.

That must have been amazing to see it the first time.

DAVID FRANCE: We were beside ourselves. We had crossed over that threshold. We were going to be able to take this movie out to the world and we were going to be able to do it safely. But then we had to sit back and just, you know, wait. We didn't know anything either about visual effects. So we thought of it as being in the oven over at Ryan's and sooner or later he’s going to take it out of the oven.

RYAN LANEY: A very slow burning oven.

FYC, people. Welcome to Chechnya is currently streaming on HBOMax and is on the Oscar finalists list for both Best Documentary Feature and Best Visual Effects.