Welcome back to the series, "Hit Me With Your Best Shot" by Nathaniel R. Each week we'll discuss a single movie via a particular shot. Anyone who'd like to participate can choose their own!

Best Prop

Best Prop

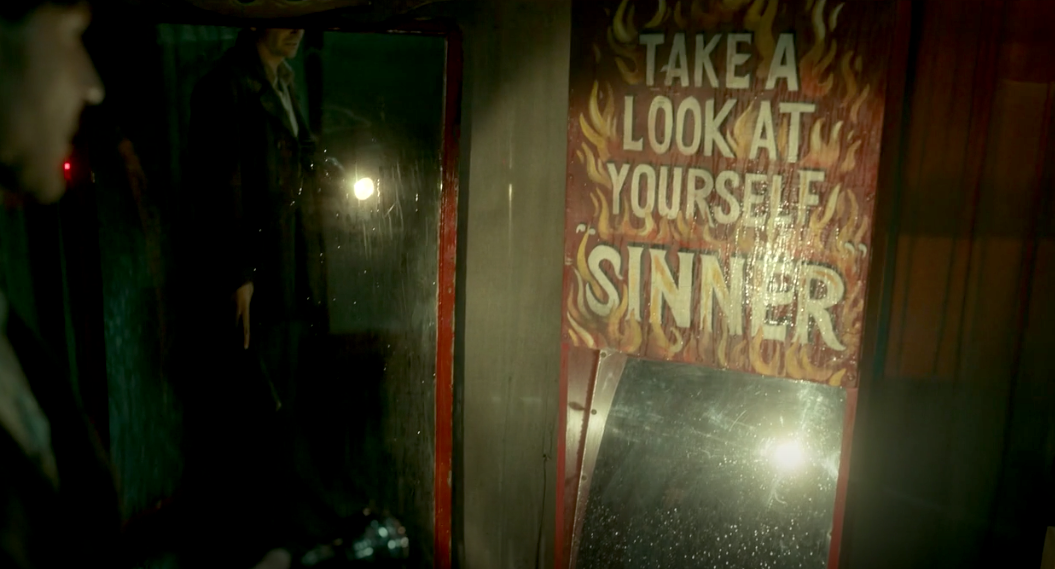

When you're reading your mark, as former circus psychic Pete (David Strathairn) teaches us, you're searching for external clues to internal damage. The fatal flaw of Nightmare Alley, up this year for Best Picture, may well be that Guillermo del Toro, though a gifted filmmaker, isn't much for interiority. But oh his surfaces! Overly lacquered beauty and the ugly rot it's faililng to hide are the greatest assets of his latest film. On that note we must pause to honor the funhouse sequence early in the film which operates like a veritable FYC ad for the Oscar-nominated Production Design. The set amazes and one particular prop in the 'funhouse', a mirror stating "TAKE A LOOK AT YOURSELF SINNER" is a perfect offhand joke. We know very little about Stanton Carlisle (Bradley Cooper) but he already knows he's "no good". The camera lingers for a second on the mirror, to make sure we do...

The first act of the film, in which Carlisle joins the circus and learns a "mentalism" act from Zeena (Toni Collette) and Pete (David Strathairn) is strangely rushed given that the Nightmare Alley is a full 40 minutes longer than the '47 noir (inspired by the same novel) despite adding little in the way of plot, characters, or cumulative emotional nihilism. That's a pity since del Toro's heart is most at home with the low-rent circus freaks, their rituals, lingo, superstitions, fetish objects, and soggy rotting lives. It is always raining and no one is ever dry for long. The big tent is their only umbrella.

In the second and third act, the precipitation continues, but turns entirely to snow as if the movie's heart has frozen over. Once Stanton leaves the circus to take his place in more reputable, yet tellingly more rotten circles, Nightmare Alley loses some of its visual mystique. Apart, of course, from what should be -- but isn't remotely due the overextended running time -- the film's centerpiece; Stanton meeting his match in Dr Lilith Ritter (Cate Blanchett).

Best Mic Drop (and runner up Best Shot)

Best Mic Drop (and runner up Best Shot)

In round one of their duel, exquisitely lit for maximum theatricality and impenetrable glamour by cinematographer Dan Laustsen, this femme fatale psychiatrist attempts to throw the mentalist off his game. She throws him a question that she knows his assistant (Rooney Mara, wasted/miscast) can't help him with. But Stanton passes her test. In one beautiful bit of blocking, direction, lighting, and performance, Stanton pivots fully around to show the crowd Lilith's hidden pistol -- a literal Chekhov's gun! -- that he's correctly "seen" with his mental powers. He's backlit and soaking up both the light and the awe from the rapt audience. Lilith remains utterly frozen in profile, like a glamorous gargoyle recently sprung from her stone perch. What is she thinking? Is she humiliated...surprised...reassessing? Perhaps she's waiting patiently waiting for the mouse to move again before pouncing.

Lilith's introduction is the film's most riveting and purposefully gorgeous sequence. It's also where del Toro's gift for surface visuals pays the strongest dividends. Pete taught us that people are "desperate to tell you who they are, desperate to be seen" but he has never met Lilith and he's misread Stanton. We're not meant to be able to peer into their souls only to know that we shouldn't. Even in this strongly lit room, they're unknowable, untrustworthy, bathed in shadow.

But for our Best Shot, which does not always mean Most Beautiful, we return to that eternal downpour that follows the circus folk around like a manifest storm.

BEST SHOT

BEST SHOT

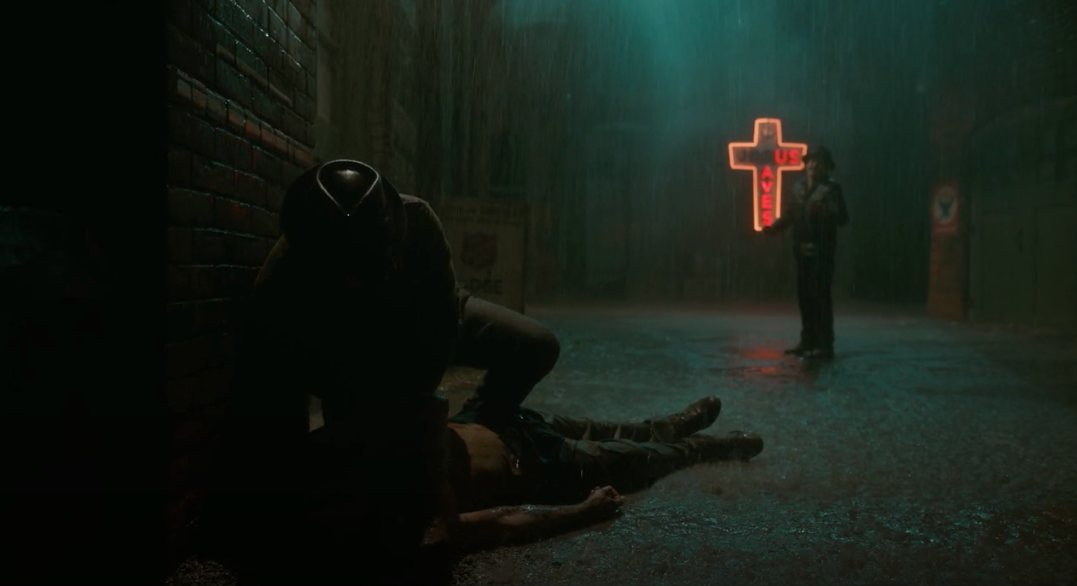

Don't pretend like you give a shit!

In this brief sequence, circus manager Clem (Willem Dafoe) and Stanton are dropping a dying "geek" (junkie) they've enslaved off at some sort of charitable home or hospital in some, well, nightmarish alley. This scene is easy to miss or undervalue the first time through the movie but on the second it pops. As their car turns the corner, a neon cross with "Jesus Saves" written on it begins to flicker and the light goes out on the Son of God; "Jesus" departs the scene for good. No more flickering.

Stanton rings the bell and assumes they'll wait for the good Samaritans to answer but Clem runs away and then chides the younger man for lingering with the body. Though this is a rare moment where Stanton appears to have a soul and a moral impulse, the sickly blue-green visuals paint him in a different light. This could just as easily be a shot of a vampire, huddled over its expiring prey. The now godless cross behind the men is reduced to a pop of garish color.

The men run off, escaping the consequences of their heinous crime. But is it the geek that died in the alley or the last glimpse of Stanton's soul? His damnation is swift. Minutes late he's gone full blaspheming predator, mocking a cop's religious beliefs and using his mother "Mary" against him. The hospital drop-off might have been a deleted scene it plays so briefly and in such an unassuming way. Instead it's a stake right through the film's heart.

ALL THE "BEST SHOT" CHOICES FROM THOSE THAT PLAYED ALONG...

NEXT WEEK'S FILM: Douglas Sirk's influential melodrama All That Heaven Allows (1955) starring Rock Hudson & Jane Wyman. It's currently streaming on Criterion Channel and available for rental on other services. It's only 89 minutes long so please join us Thursday February 24th by posting your own "Best Shot". We'll link up if you let us know you did.