One way or another, artists can't help but put some part of themselves into their work. It might not be obvious or a direct expression of character. It might not even be conscious on their part. However, it's there for those willing to see, from works by the most self-effacing hacks to world-renowned auteurs. Hayao Miyazaki is no different, though he's sometimes prone to underselling just how personal some of his pictures can be. Of course, there's no denying the introspection happening in his most recent "last films," and not even the director has tried to distance The Wind Rises or The Boy and the Heron from such interpretations. But there's more self-portraiture in his filmography than just those late-career triumphs. I'd say there's a lot of Miyazaki in a little witch who loved to fly…

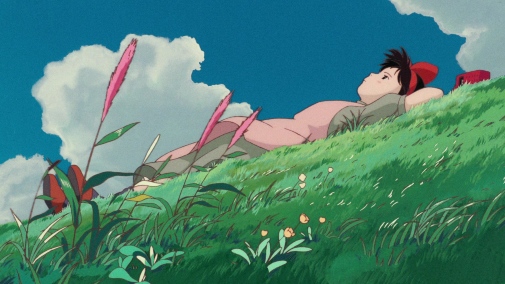

06. KIKI'S DELIVERY SERVICE (1989)

Directing Kiki's Delivery Service wasn't in Hayao Miyazaki's plans. By the time Studio Ghibli got the rights to Eiko Kadono's novel about a young witch, both its animator co-founders were busy with other features – 1988's Grave of the Fireflies and My Neighbor Totoro – so neither Takahata nor Miyazaki could take charge. The adaptation, sponsored by Group Fudosha and the cat-loving Yamato Transport Inc., was then conceived as an opportunity to let the younger artists at the studio shine, the beginning of a new generation of animators. It was to be a one-hour special of modest ambition, with Miyazaki supervising in the role of producer. As we all know, this state of things would fall apart.

In a move that would repeat time and time again over Ghibli's history, the master grew dissatisfied with the work. At first, he only took over script-writing duties, completely re-imagining what had been done till then. Afterward, he'd take the crew on a Grand Tour of Europe, shaping their conception of the film's fictional setting as an amalgamation of various cities and cultures. By mid-1988, his influence over the project was so overwhelming that the Studio officially announced Miyazaki as its director. The original author was not happy with this revised interpretation of her work, mind you.

The filmmaker had focused much of his story on the witch's failures, struggles, and ever-encroaching unhappiness, going against the book's sunnier outlook. This could result in a sour film and spoil its lasting impact, but, funnily enough, that hint of gloom is precisely what makes the picture so powerful. You see, in its tale of a kid witch striving to live in the big city and stride into adult responsibilities, Kiki's Delivery Service became a powerful reflection of its makers' particularities as artists. And as we all should know, the path to universality is paved with hyper-specificity. To this day, I've never encountered another film that so effectively illustrates the perils of burnout, of making your passion into a job and the deadening toll of it all.

As time passes and I grow up, grow older, the film's reflection becomes more crystal clear, both daunting and a comfort. There's great wisdom in its implications that adulthood is learning to deal with disappointment, accepting what is inevitable. Or how hurtful it can be when you put your heart and soul into something only to be met with the ungratefulness of a girl who doesn't appreciate her grandmother's herring pie. Loss is inevitable, and sometimes you lose the thing that gives you purpose and makes you feel like you are worth anything. Look past the froth, and Kiki's Delivery Service has as much to say about the human condition as Miyazaki's more outwardly epic projects.

It's also an intimate self-reflection for its auteur, whether he admits it or not. Consider that Kiki's vocation is flying and how, throughout his entire life, the director has associated flight with a sense of cosmical freedom, the highest form of personal expression and liberation. When she finds herself in a depression episode and can't fly, it's hard not to think back to all that Miyazaki has shared in interviews and documentaries over the years - his assessment of himself as a depression-prone personality and the foundational importance of working in his conception of self. In Kiki, we can see why those exhausted retirements keep popping up but also why they never last. Through Kiki, Miyazaki stumbles, but ultimately, he soars.

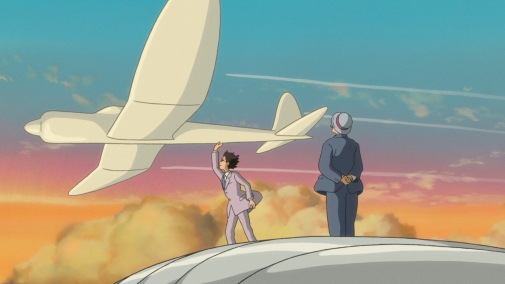

05. THE WIND RISES (2013)

In the Kingdom of Madness and Dreams documentary, the cameras capture some of The Wind Rises' production, offering insight into the process and the film's behind-the-scenes' particularities. In a revealing tidbit, an animator expresses frustration over Miyazaki's notes about the airplanes' flight. For the junior artist, his director talks about capturing the machine's movements as they are, but, in truth, what the master envisions is something altogether different from reality. On-screen, Miyazaki wants to see the planes as they exist in his imagination, with their oneiric qualities, engineering spectacle, and overwhelming beauty projected straight from his dreams.

The Wind Rises isn't so much about the History it depicts, the mechanics that allow planes to rise above the clouds. Instead, it's about the artist's dream and what a curse it can be. It's about Miyazaki's eternal contradiction. He loves military aircraft with all his heart as it's befitting the scion of the erstwhile Miyazaki Airplane company. But he also loathes their deadly purpose. Those beautiful creations wouldn't exist without war, yet he hates that consequence of mankind's violence and has dedicated much of his career to spreading messages against it. How does one sing a song of passion while acknowledging an inherent evil to that most beloved thing? Is it possible to compartmentalize? Is it right?

While telling the life of Jiro Horikoshi, Miyazaki is telling his own story, revealing and reveling on the paradoxes that make him the person and artist he is today. Relationships depicted in the film echo with the sound of auto-fiction, as do the dreams and delusions of its characters. But it's not merely a work of inward meditations with an aggrandizing twist. Miyazaki is critical of Jiro and himself, complicating some people's assertions that The Wind Rises is an apologia for a man whose contributions to Japan's military machine caused countless deaths. The film stares straight at the void while trying to explain why someone would willingly dive into it. Without losing its Humanistic ethos, The Wind Rises considers the best and worst of us.

Every gesture of overt romanticism is undercut and imbued with a sinister edge. Even the love story between Jiro and his wife becomes tainted by neglect in a time of need, by the terrible mission that entrances the man. There's a strain of naivete throughout The Wind Rises that eventually emerges as lies one tells to themselves, a pitiless conclusion that corrodes the miracle of flight without denying its wonder. And then there's the animation, the precise cutting, and luxurious symphonies – all combined to make this one of the director's most mature masterpieces, as gorgeous as it is uncomfortable, every delight lined with sorrow.

04. THE BOY AND THE HERON (2023)

Covering a film festival often leads to writing down immediate reactions with little time to ponder and reflect on a picture. There's no time to let it age in your memory and see what most resonates even after more granular details have faded. All this is to say: While I stand by my ecstatic TIFF review of Miyazaki's latest, there's a lot I didn't articulate back then that now feels crucial to my understanding of the film. Moreover, seeing numerous friends and acquaintances struggle to engage with it revealed how insular the story's solipsism can often be. It doesn't make me appreciate the film any less, but provides a necessary contrast.

Simply put, The Boy and the Heron is Hayao Miyazaki's most personal work, so achingly intimate it can become alienating if one isn't aware enough or willing to peruse its mysteries through a prism of autobiography. I'd argue that the emotions are strong enough to sustain the confused viewer, though one can't deny how convoluted its dream logic can sometimes become. It's the story of a boy who watches his innocence go up in flames during the war, who lives with the loss of his mother and the gradual of another maternal influence. It's the story of someone who hates himself and the confrontation with an internal storm through fantasy beyond time and space.

It's also the story of Ghibli, Miyazaki's past and present, and all the fallen stars along the way. Over its long production, the aging director saw two of his most essential collaborators die, their absence later manifest in the fabric of the narrative. Colorist Michiyo Yasuda lives in the young mother that will guide her future progeny through the unknown. Isao Takahata looms over the Granduncle figure whose centrality in the original plot was too painful to maintain after the real man's demise. But Miyazaki is also in all of them, in the bird king who terrorizes his army (of animators), the boy struggling, and the older figure who watches all he created bound to ruin.

"I trained successors but I couldn't let go. I devoured them. I devoured their talent. There was no one left to take over," is something the director said in documentary profiles, but it could as easily be a line roaring over the picture's last act. The master's forgiveness of the boy who doesn't want to perpetuate what the older generation created is the director and his son, dragged into the animating business against his will and lambasted for failing to reach his ancestor's success. And it's so much more, a plurality of readings, all valid and true. All of them aching with raw insight that only the most surreal of fiction can hope to translate. It's insular if you approach it through intellect alone. Surrender to the visceral feeling, and it might start to make sense.

Takahata, Miyazaki, the Granduncle – they all want copies of themselves, while knowing such demands are impossible. Learning to forgive those who can't make it possible is a step in the right direction, but it doesn't erase the hurt. Their towers of fantasy will crumble in death, and that's alright. The grief of friends and collaborators, of partners in crime and art, of sons without mothers, is a song sung throughout The Boy and the Heron for death is what unites everything in the end of all ends. As morbid as it may seem, there's comfort in the picture's confrontation with mortality. In its embrace, we might know peace, and even if we leave no lasting mark behind, the love and exhilaration still make life worthwhile.

The Boy and the Heron is as tragic as it is hopeful. It's as bruising as magical, so full of invention from a litany of animators who returned to Ghibli after building their careers beyond its limiting structure. They all came back to help Miyazaki complete this opus at an age when his physical ability was starting to wane. Such contribution helps the film look like nothing else in the director's filmography as if the screen were shapeshifting along with the narrative, always in flux. Naysayers will conclude it's chaotic, but I choose to see a miracle within. Even thinking about it makes me tear up, and listening to Hisaishi's score is enough to draw those tears down my face. Maybe I'm an easy mark... and I wouldn't have it any other way.

I've written about all of today's films before. So, while I tried not to be too repetitive, some redundancy was bound to occur. You can check out those past posts if you're interested. There was a meditation on Jiji's role in Kiki's Delivery Service for National Pet Week, a How Had I Never Seen entry on The Wind Rises, and my TIFF review of The Boy and The Heron.

The 1989 and 2013 films are both streaming on Max. You can find The Boy and the Heron in theaters for a short re-release to celebrate its Oscar win.