TIFF '23: "The Boy and the Heron" goes into the unknown

Saturday, September 9, 2023 at 3:00PM

Saturday, September 9, 2023 at 3:00PM  Miyazaki's "The Boy and the Heron"

Miyazaki's "The Boy and the Heron"

Hayao Miyazaki's last last picture before his latest last picture – already being discredited as such by Studio Ghibli VP Junichi Nishioka – saw him take on the model of a relatively conventional biopic. Despite its wavering between reality and dream, the now and the before, The Wind Rises represented one of the director's most straightforward efforts, doing away with the fantasy elements that defined most of his career. Had it stayed his swan song, it would have made for a career's closing chapter shaped like an intersection of culminating obsessions and stylistic disruption. The Boy and the Heron, previously known as How Do You Live?, posits a inversion of those paradigms. Oft-repeated ideas are invoked only to be collapsed, while tone and style return to the land of fantasy and dream logic.

Before reading ahead, A WARNING. This film will probably be best enjoyed by those who go into it blind, similarly to how Japanese audiences received it. If you want that experience, be satiated in the knowledge this is another masterpiece by Miyazaki. If you yearn for more, come with me down to a place that's no place within a time without time…

To live is to be in the process of dying, every step you take one step closer to the end. That point of no return may present itself as a new beginning, or perhaps nothing at all, merely the ceasing of existence. Whatever the answer, no living soul knows it for sure, making it a great unknown looming over our collective horizon. Uncertainty is an absolute, no matter what some might say. As would be expected, many a great artist has dealt with the subject in their art, works that take as many forms as there are artists in the world. Hayao Miyazaki, however, hasn't partaken in the morbidity until now.

Plenty of his films deal with loss and grief, some with violence. But none before came close to what The Boy and the Heron is attempting. Perhaps contemplating that, one day, his final film will really be a final film, the director decided to push his cinematic introspection to new depths. The result teeters on the knife's edge of eternal uncertainty, proposing an odyssey that starts in familiar territory and ends in oblivion, ruled by dream logic along its course. There's a chaotic verve to it, a willfulness to be illegible if not for how its emotional timbre resolves itself in the end, ringing truer than truth.

It all begins, as it often does in Miyazaki's cinema, with a child. The titular boy is Mahito, living during the war years when, one night, a firebombing hits his mother's hospital, taking her away in flames. As far as opening salvos go, this is a doozy of Ghibli classicism stretching itself into Expressionism, the world bending around the shock of panic (un)settling into grief. Apart from the running Mahito, most of the people on screen are distorted into shades, the very air and dimensionality of the frame twisted by more than just the fire's heat. Approached as an immediacy, the action already looks like a trauma remembered, tomorrow's memory of today.

Two years later, Mahito's father has decided to relocate them from the city to the countryside, where his wife's family owns a vast estate. He's also married her sister, Natsuko, and the couple's expecting their first child together. Looking at the woman is to look at a ghost, but the same could be said for Mahito. The boy's got his mother's face and a voice inching toward adulthood, a spirit numbed by depression that, in one startling moment, escalates to self-harm. If nothing else will, that action must surely elucidate the viewer regarding what kind of film they're watching – a barbed thing, innocence spoiled into something dark and complicated.

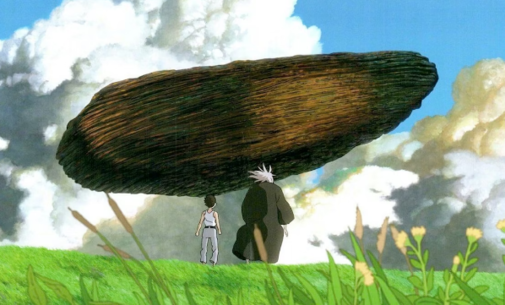

So far, most of The Boy and the Heron could play as a companion piece to Isao Takahata's Grave of the Fireflies if not for the titular bird. Flying into the house, he seems to taunt Mahito, even before animal shrieks turn into words and a toothy grin erupts from its beak. When Natsuko grows ill and disappears, her nephew made stepson shall follow the bird's call into a mysterious castle from the sky, an alien-like derelict. Its labyrinthine hallways and porous floors lead to a dimension lost from time and space, lost from reality though its inhabitants resemble a corrupted version of the real.

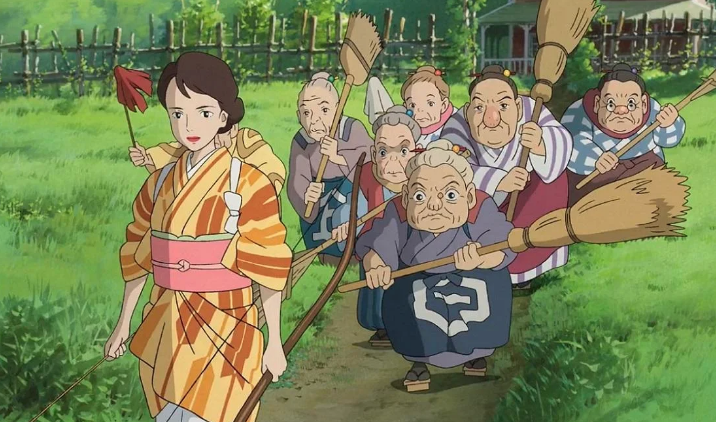

They're gray herons with men inside and pelicans so starved of life over a dead sea that they devour souls to be. They're women made younger, a mother meeting her son in a girlhood that should be impossible without even mentioning the trespassing of death. She wields the fire that will kill her future, a violent notion that sickens one to tears. On the opposite end of the tonal spectrum, parakeets are man-eating giants, enthusiastically feudal and ravenous. The beauty of flying objects has been retrofitted into avian grotesquerie, while the prototypical Miyazaki heroine is an existential contradiction under the watch of Granduncle.

Such a figure may seem peripherical at first, a backstory nexus with no effect in the main narrative. However, he proves pivotal to Miyazaki's plans. Through him and Mahito, the director expresses a torrent of self-examination that's painful to witness. A madman building and rebuilding worlds, playing with his toys, trying to pass on the act of creation to his bloodline to no effect. What's more, the great doing might have been an undoing, bound to destruction one way or the other. Time running out, and worlds colliding, you can sense the artist looking back to what came before and playing with his building blocks in return to everything that turns into nothing, regret and elation one and the same.

Between mourning for others, oneself, the great metaphysical questions of the human condition somewhere in the middle, The Boy and the Heron is a staggering piece of storytelling. It's also an animation miracle whose wonders go beyond its burning introduction. For example, Miyazaki has seldom conveyed such subtle performances from the cartoon faces as he does here, and, if possible, his control over depictions of the body in motion is even more impressive. Several shots linger in movements, grounding the drawings in the physical actuality of the characters, while others stylize them into riotous 2-D physical comedy that conveys everything through contrasting gesture. Then again, even if they were just excuses to show off skill, this director has earned the right to boast. Indeed, if The Boy and the Heron gets a single point across, it is that, when Miyazaki goes to the great unknown, cinema will lose one of its greatest masters, someone who never ceased to show us its limitless possibilities.

The Boy and the Heron will be distributed by GKids in the USA. It's scheduled for a December 8th release.

Asian cinema,

Asian cinema,  Hayao Miyazaki,

Hayao Miyazaki,  Japan,

Japan,  Review,

Review,  Studio Ghibli,

Studio Ghibli,  TIFF,

TIFF,  animated films,

animated films,  animation,

animation,  anime,

anime,  film festivals

film festivals