Michael C here to give you a sneak peak of a Pixar pleasure headed your way soon.

High on the long list of reasons to love Pixar is their devotion to bringing top quality animated shorts to the movie-going masses, a tradition they are keeping alive pretty much single-handedly. And they are on a roll too. With such titles as Presto, Cloudy Day and the great Day and Night, my love of which I’ve already documented here, they are developing a body a body of work to stand beside the great catalogues of classic Disney and Warner Bros. cartoons.

High on the long list of reasons to love Pixar is their devotion to bringing top quality animated shorts to the movie-going masses, a tradition they are keeping alive pretty much single-handedly. And they are on a roll too. With such titles as Presto, Cloudy Day and the great Day and Night, my love of which I’ve already documented here, they are developing a body a body of work to stand beside the great catalogues of classic Disney and Warner Bros. cartoons.

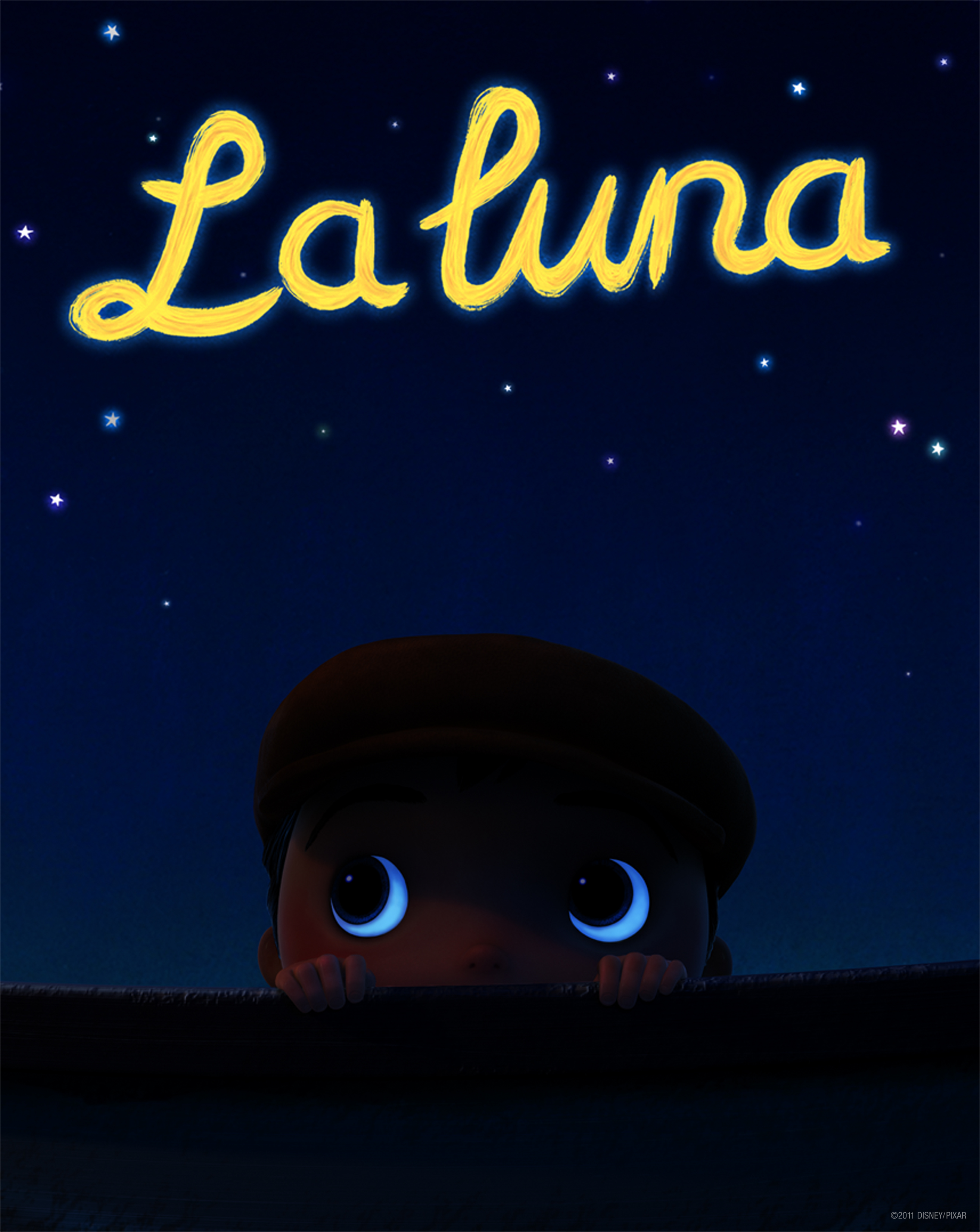

Now having attended a sneak of La Luna, the new short most of America will see attached to Brave, I am pleased to report they have another winner on their hands. La Luna is a fable about young boy caught in an inter-generational conflict as he joins his Papa and Grandpa for the first time in their nightly work. The slow reveal of the exact nature of that work is one of the film's delights which also include its elegant dialogue-free storytelling, glowing moonlit atmosphere and an especially lovely Michael Giacchino score.

La Luna is the baby of Enrico Casarosa, who is making his directing debut with this love letter to his Italian roots. He began with Pixar as a story artist on Cars and Ratatouille, and he is currently working as Head of Story for an upcoming feature. I sat down with Casarosa to discuss his new film, his influences, and to see how much I could peek behind the Pixar curtain.

Michael Cusumano: I got the impression that La Luna is a very personal film for you. Am I right in saying that?

Enrico Casarosa, Head of Story for Pixar

Enrico Casarosa, Head of Story for Pixar

Enrico Casarosa: Yeah. I really felt I wanted to find an emotional core to it and I think Pixar is pretty adamant about trying to find connections. The directors need to find that personal story to tell. So I really looked at my childhood. I grew up in Genoa, in Italy, and I grew up with our grandfather in our house, and my dad and my grandfather never got along. So I would have very long dinners where I was definitely in the middle of these two guys, talking to me but never talking to each other. So that feeling of being a little bit stuck in the middle was something I was after. And I would be really fun to try to give a positive message of a kid choosing his own - you know - it’s not Papa’s way, it’s not Grandpa’s way, but it’s his own way. So he finds his own road. I thought that was worth sharing, it could be the core of it.

Then I mixed that with a completely fantastical kind of setting to juxtapose the very personal with something more fantastic. The inspiration to that is a lot of literature. I’m a big Italo Calvino fan. He’s a wonderful writer that we read in high school in Italy. He has, all through his novels and short stories, making the very fantastic juxtaposed with very simple characters, peasants, so that’s the kind of a feel I wanted to capture. I wanted them to be very poor, you know, working the land, fishermen. Then I thought it would really be a great juxtaposition when you find out their job is actually pretty mythical.

How is it possible to get such a personal story through such a collaborative process? [MORE AFTER THE JUMP] Animation, more so than even regular filmmaking, you rely on so many people. How do you keep from losing that personal touch?

Enrico: It’s really about the story. If you get people behind that story. What happens is you get a lot of feedback as you go forward and direct this. We still go through a process of making storyboards reels and honing in and sculpting it and pitching it and getting feedback from the other directors. That’s a wonderful learning experience. What you do as a director is learn to listen to the specific notes that you want to take care of. What are great notes? What are additions and changes that are going to be true to the story? What are the times when you’re going to need to hang on to your flag and not let go? It’s a mixture of that.

Very often I would get notes and I was offered some solutions from super smart, wonderful directors, but they wouldn’t be necessarily what I thought was right for the movie. But it would tell me there was a little bit of a problem there, maybe I should find my own solution to make that moment stronger.

So the core was there and I felt good and I think with all the feedback around me it just made it stronger.

So the collaboration brings you closer to your own vision?

Enrico: I think so. I was lucky to have a core that I felt was there and was solid from the beginning. So I think that entitled me and empowered me to make decisions.

Disney/Pixar is one of the last, if not the only studio, still committed to the format of the short film and bringing it to a mass audience. How do you feel about that from your perspective inside Pixar?

Enrico: I feel so privileged and lucky that that’s the case. They believe in it as an art form. They believe in it as part of the experience of seeing a feature, being the appetizer to your main meal. And I think they believe in it, of course, as in a growing talent potential, and also to put people in different capabilities.

Our jobs are so compartmentalized that whenever you get a chance to step out a little bit of those specific jobs it’s a good thing, and the company realizes that. And a short is way less people, so you get to do a little more. You have to. Everyone has to take a little more responsibility. Maybe you’re going to have a Head Animation Lead who has never been an Animation Lead, so it’s a learning opportunity for them to take on more and different responsibilities.

Then you also have the wonderful part of just having a small team, so that it feels like a little independent project. So there’s limitations cause maybe you don’t have the people you need all the time, but there’s a lot of camaraderie and closeness.

Would you say there is more creative freedom on a short film compared to a full feature?

Enrico: Yeah, I think that’s fair to say. Because we don’t have to go out there and make millions of dollars, you know. I always say there’s the commerce and there’s the art side and the shorts can lean on the art side a little more.

There’s such a gentle spirit to your film it’s hard to imagine it getting through the feature length process.

Enrico: Yeah. I still think there’s plenty of exploration that even a feature can make. But you have to bring a lot of people to these feature length movies. That’s one of the limitations. And that’s where I think Pixar has struck a wonderful balance because we’ve still been able to make a lot of gutsy, interesting movies. But you still have to get families and everybody in there to enjoy it, so it’s a much tougher puzzle to put together, a feature. Can you make it feel like a personal emotional story and still please everybody?

I was fascinated and pleased to see that you listed Hayao Miyazaki as a major influence. Can you talk a bit about what his work means to you and are there any non-animated filmmakers you would say influenced your film?

Enrico: Miyazaki, I’ve watched and rewatched and studied those films so many times. I grew up with some of his TV series in the Eighties, and I didn’t even know that it was him at the time. Then in the Nineties when I discovered more and more of his movies I made the connection. Some of his TV series like Future Boy Conan I was watching when I was eleven, twelve, so they’re a little bit in my DNA, so a huge influence on my work by osmosis almost. I think that’s the way I draw because I’ve looked at his work so much, I love it so much.

Then if I had to say others. You know, we all love so much cinema. We are kinda geeks about cinema in general. I love Fellini, I love Kurosawa, I love Ozu. I love a ton of Asian cinema. I’m a bit all over the place like that.

Was I wrong to see a little silent comedy in some of the storytelling with the use of images to show the generational differences?

Enrico: We believe, definitely, in pantomime, and those are wonderful movies we all look at. The General, I’m thinking. They’re maybe not a direct influence but between Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton we have definitely watched carefully. So wonderful that they can tell those stories without dialogue.

How does something go from concept to production? How do you pitch it, how does it get a green light at Pixar?

Enrico: When I pitched it I made roughly thirty images. We call them beat boards or image boards. It’s almost as if you did a kid’s book and made some rough illustrations for it. Page by page you tell the story. That’s how I did it, and that’s when they said, "We like this one, let’s make this one."

I imagine in a company with so many creative people there’s a lot of competition, lots of ideas.

Enrico: You pitch to John Lasseter and ultimately he’s the gatekeeper. He’s the executive producer of all the shorts, so he’s the one. He’s got a great instinct. He gave us great notes, very key notes. He’s the one who can say, “Nah, let’s look at this again maybe next year or in six months. I love this one. Let’s make this one.”

But again, the idea is what matters. I don’t think there is full-on competition. There is a lot of sharing. We tell each other a lot of stories. We pitch each other a lot of stories. We are used to brainstorming a lot. In the room we are often brainstorming whatever problem a feature has: How do we solve this? How do we make this better? How do we come up with this interesting action scene? So that’s something that’s part of our genes. I pitched this very early on to some story artists, peers, and some of the ideas that end up in the movie are pitched by them. It’s about being willing to share good ideas and feedback. We are very used to just giving feedback to each other.

Pixar has such a consistently high level of quality, more so than just about any other studio. What is it that Pixar does differently that produces such consistent results?

Enrico: I think it goes back to very, very honest feedback. There is a stable of really diverse, very smart, talented directors and they all sit down on each movie. We screen the movie, we screen these rough versions. And you sit down for two hours and hash it out. How could it be better? What worked well? What didn’t? And they’re very honest with each other. And they also come from different sensibilities, and I think that’s the strongest asset, cause you’re going to get wonderful feedback. People want you to succeed. I don’t think that’s always the case – that’s not the kind of support you get at other studios.

So it’s really at the base of the culture of openness and honest give and take. These collaborators, Pete Docter, Andrew Stanton, John Lasseter. They’re brutally honest people, but that’s what you need. And they’re there to try to make it better. They all have a vested interest. They all want to tell good stories. So that’s the wonderful part. On the receiving end it crystallizes even more so, cause they’re there just wanting you to succeed. It’s very altruistic and it doesn’t always happen.

more animated films, short films, and interviews