1963 is our "Year of the Month" for September. So we'll be celebrating its films randomly throughout the month. Here's Daniel Walber...

Once upon a time, there were two production design categories at the Oscars. From 1945 through 1956, and again from 1959 through 1966, color films and black and white films competed separately. The Academy nominated ten films every year after 1950, creating a whole lot more room for variety.

Once upon a time, there were two production design categories at the Oscars. From 1945 through 1956, and again from 1959 through 1966, color films and black and white films competed separately. The Academy nominated ten films every year after 1950, creating a whole lot more room for variety.

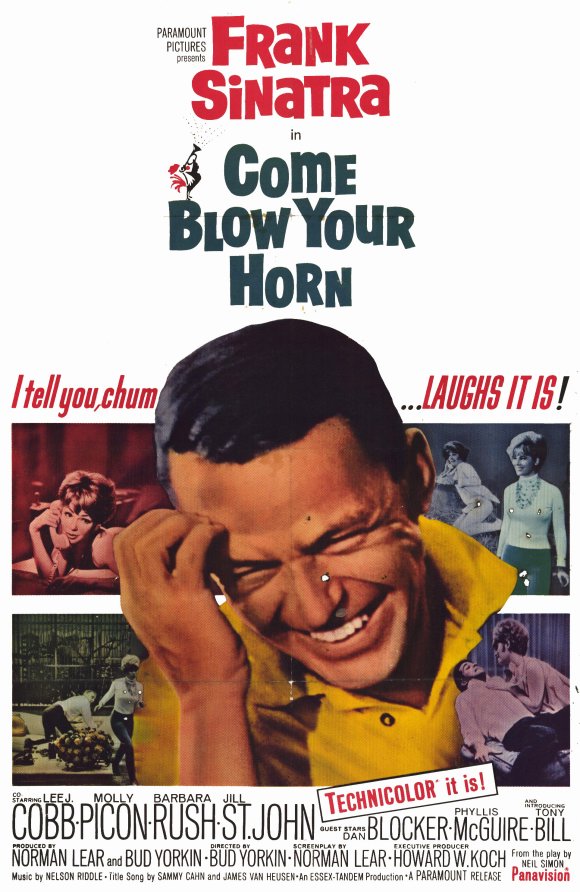

This especially benefited comedy, a genre that has since fallen out of favor with Oscar. And while Come Blow Your Horn might not be the funniest of the 1960s, it is certainly one of the most deserving nominees of the era. Adapted by Norman Lear from a Neil Simon play, this Frank Sinatra vehicle stages most of its antics in one of cinema’s most luxurious apartments, the work of art directors Roland Anderson (Breakfast at Tiffany’s) and Hal Pereira (Vertigo) and set decorators Sam Comer (Rear Window) and James W. Payne (The Sting).

Sinatra plays Alan Baker, a salesman for his family’s plastic fruit business. His boss and father, Harry (Lee J. Cobb), is perpetually enraged by his son’s libertine Manhattan lifestyle. Harry and his wife Sophie, played by Yiddish theater legend Molly Picon, live a quiet life in Yonkers with their much younger son, Buddy (Tony Bill). But when Buddy runs away from home to live large with Alan, all hell breaks loose.

Alan's apartment in question is a spotless and opulent apotheosis of mid-century design. The open living room makes the place seem enormous...

Every piece of furniture, every work of art, every little accent catches the eye. There’s enough in the space to keep the viewer impressed for hours, crucial for a script that places almost all of the action in this single set.

It also has a beautiful view, or at least a convincing deep blue recreation of what an East Side view of the city might look like.

And if you look closely in the center of the above image, you can see a large set of ornamental scales. They’re a wry joke on the part of the production designers, an upright symbol of justice in the apartment of a man who is juggling three different women and ignoring his professional responsibilities.

The production design collaborates with the comedy. Another great example comes from the back of two refrigerators. First is that of the Baker parents, who have saved so many leftovers that one could be blinded by all the aluminum foil.

Alan’s fridge, meanwhile, has nothing in it but a can of beer, a celery stick and a solitary red heel.

The film culminates in a wild party that transforms the space. Suddenly there are new lamps everywhere, a wide array of colored candles, and cool sheer fabric hanging from the ceilings. Everyone is playing Strip Scrabble. It’s a hippie extravaganza, or at least a Hollywood idea of one.

Alan takes Buddy into the kitchen to talk some sense into him. A lamp from the living room is now sitting above the fridge and there are enormous rolls of fabric all over the room. The sharp production design team not only illustrates the party’s excess, but also mines its materials for more humor.

The quintessential sight gag comes earlier, however. Sophie has been left alone in the apartment by a twist in the script. Alan’s phone won’t stop ringing. She tries to handle messages from both his various women and their vengeful husbands, but she can’t find a pencil anywhere in this overdecorated apartment. It’s a comic tour de force from Picon, and probably the best thing in the film.

The punchline is delayed until Alan comes home and also needs a pencil. It being his apartment, he finds one easily. He keeps them in a sleek case right next to the phone. It’s streamlined and tasteful, and utterly unrecognizable to his poor mother. It’s a perfect example of 1960s production design, relishing mid-century modernism while also making fun of it.

More from "The Furniture":

The Lobster and its phony flowers

Absolutely Fabulous best design moments

Beaches and color coded characters

Deadpool the junkyard